About two decades ago, American writer Marc Prensky (2001) coined the term “digital natives” to describe students who grew up with digital technologies. He suggested that they are the “native speakers” of the digital language of information technology.

Although the term is somewhat vague in defining students’ skills and competencies, it depicted a significant social and cultural change and its impact to students, teachers, and the American education system. As a result, many educators and researchers became intrigued and conducted research to investigate and validate the potential impact to students and its implications to teaching and learning (Bennett et al., 2008; Kennedy et al., 2008; Kirschner & De Bruyckere, 2017; Margaryan et al., 2011).

Putting aside research results for now, my personal and professional experiences led to a belief that the development and acquisition of any skill or competency is typically a result of intention and persistence, especially in an age where new gadgets and tools are constantly being invented and designed for specific purposes or group of users. It takes time to just familiarize yourself with the basic functions of a smartphone or a small home appliance, let alone complex systems that are designed for knowledge dissemination, collaboration, and communication.

According to Prensky’s definition, I can arguably be considered a “digital native” since I attended high school in 2003. However, at that point in my life, I had only taken one or two computer classes at school that focused on basic typing skills. I was bewildered by the dark, silent screens and did not even know how to start the machine when I entered the computer room for the first time. Therefore, it was difficult to convince anyone that I, as a high school student, spoke the native language of any technology.

Fast forward to 2016 or 2017, when I was coaching a few high school students to create a video for self-introduction. I was surprised that two of them could not even type properly on a computer. Have you seen someone dancing with one finger, and one finger only, to painstakingly search and press each letter on the keyboard? That was the reality, and it became an epiphany to me that we cannot take any skills for granted. If someone appears to be average, not even good or great, in a certain area, it is likely because they have spent some time and effort, in or outside of school.

It is no wonder that researchers seem to be resistant toward the concept of “digital natives.” Bennett et al., (2008) found a lack of evidence and called for more investigation and empirical research on “digital natives”. Kenney et al., (2008) suggested that we cannot assume that new generations know how to employ technology-based tools strategically to optimize learning experiences. Margaryan et al. (2011) argued that students may not be as connected, socially networked, or technologically fluent as previously assumed. Kirschner & De Bruyckere (2017) concluded that “there is no such as thing as a digital native who is information skilled.”

It is evident that actions need to be taken to respond not only to the evolving landscape of education, but also address the skill gap in the digital age. As an important first step, in April 2023, the B.C. Ministry of Post-Secondary Education and Future Skills published the Digital Learning Strategy which lists and describes eight digital literacy competencies in detail and serves as a valuable resource for digital learning.

As an official guide, it also provides an unequivocal answer as to who needs to develop digital literacy skills. Under each and every competency in Appendix 2: The B.C. Post-Secondary Digital Literacy Framework, you will find these phrases:

- “If you are a digital citizen, being digitally literate means…”

- “If you are an incoming learner, being digitally literate means…”

- “If you are an educator, being digitally literate means…”

It is clear that all of us are included in the framework, regardless of our age differences or skill level.

The challenge is, though, how to support the development of digital literacy at an institutional, program, and course level, and how to cope with the evolving nature of digital technology.

If you are eager to explore digital literacy in teaching and learning, here are a few actions you may start with,

- Read the Digital Learning Strategy document

- Explore the potential of using e-portfolio in your course

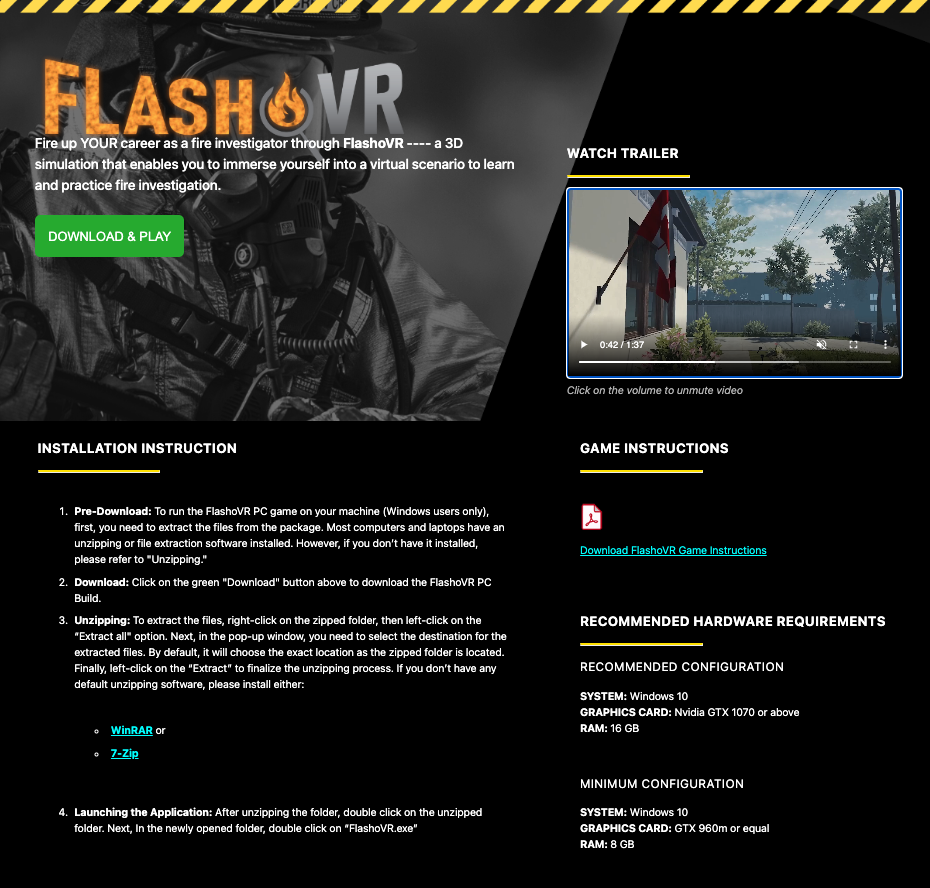

- Collaborate with CTLI on simulation projects

- Stay open and curious about new technologies, including AI-based tool

Reference

Ministry of Advanced Education and Skills Training. (2023, April 13). Digital Learning Strategy – Province of British Columbia. Retrieved from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/education-training/post-secondary-education/institution-resources-administration/digital-learning-strategy

Bennett, S., Maton, K., & Kervin, L. (2008). The ‘digital natives’ debate: A critical review of the evidence. British journal of educational technology, 39(5), 775-786.

>Kennedy, G. E., Judd, T. S., Churchward, A., Gray, K., & Krause, K. L. (2008). First year students’ experiences with technology: Are they really digital natives?. Australasian journal of educational technology, 24(1).

Kirschner, P. A., & De Bruyckere, P. (2017). The myths of the digital native and the multitasker. Teaching and Teacher education, 67, 135-142.

Margaryan, A., Littlejohn, A., & Vojt, G. (2011). Are digital natives a myth or reality? University students’ use of digital technologies. Computers & education, 56(2), 429-440.

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital Natives, digital immigrants. marcprensky.com. Retrieved from https://www.marcprensky.com/writing/Prensky%20-%20Digital%20Natives,%20Digital%20Immigrants%20-%20Part1.pdf

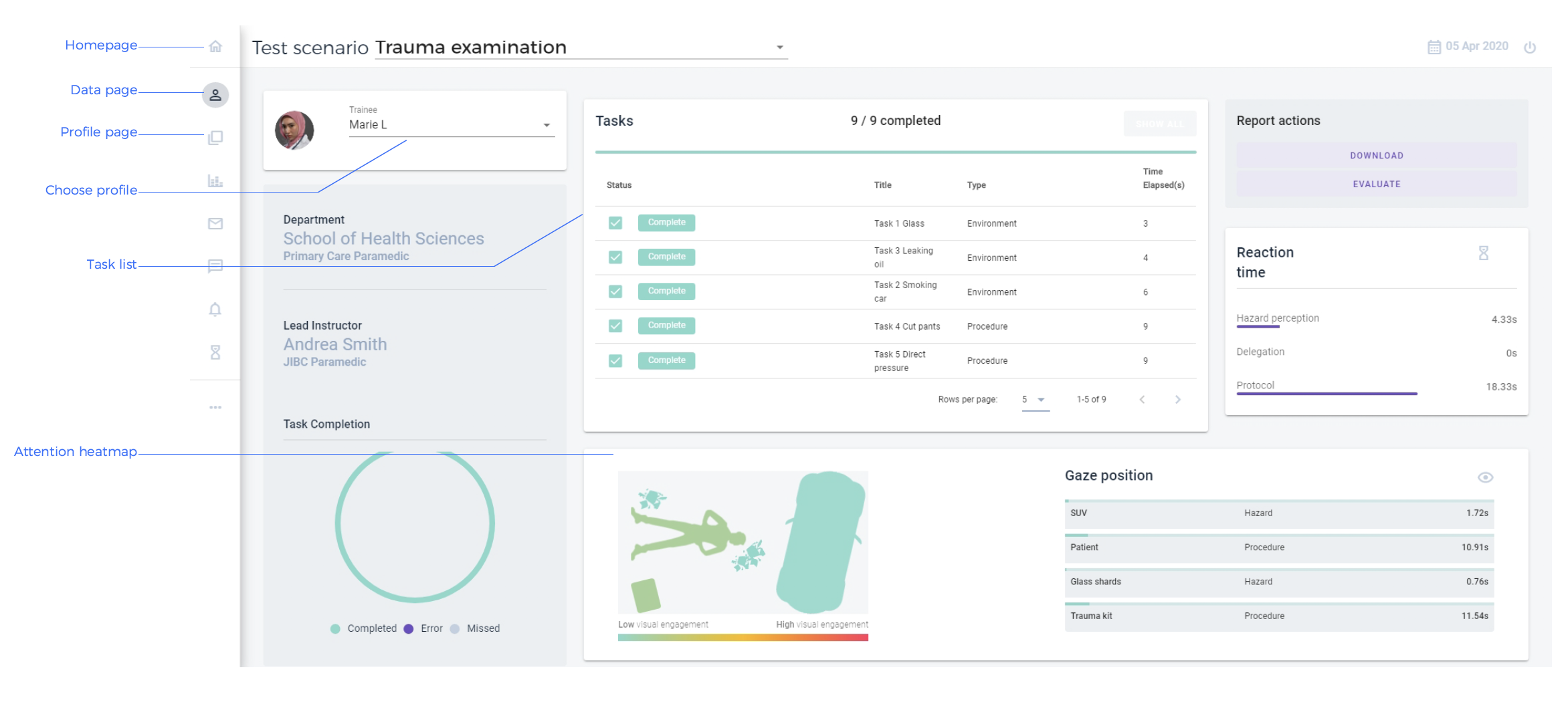

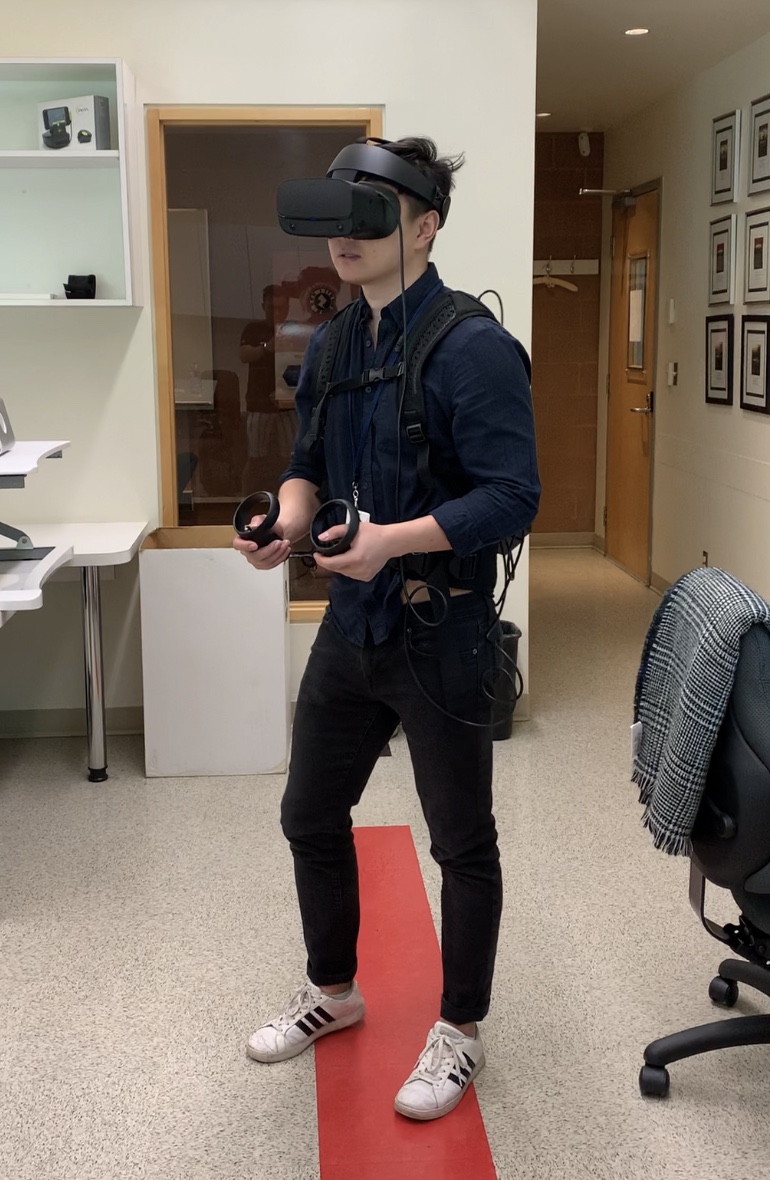

Photo from the UDL Workshop

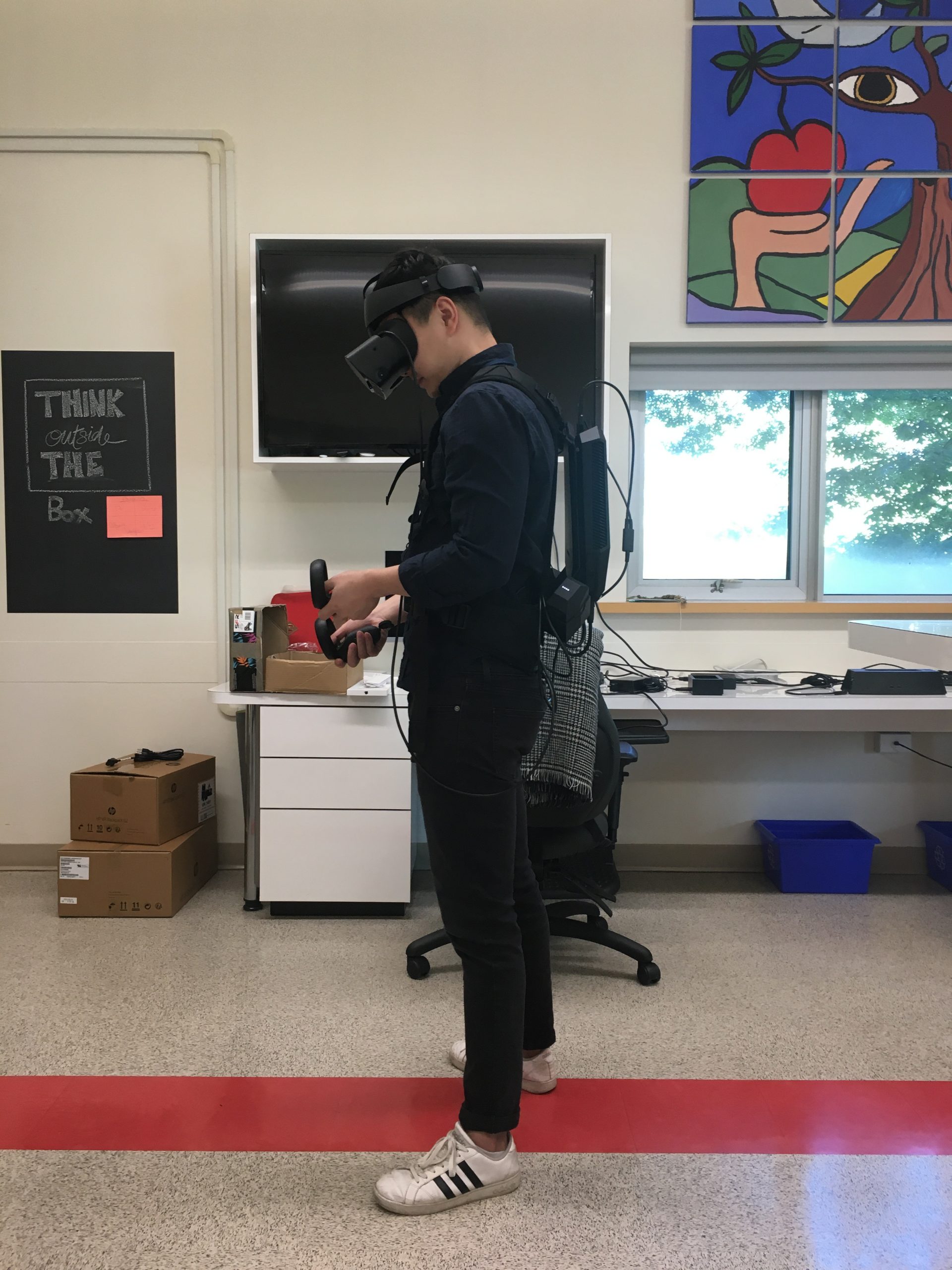

Photo from the UDL Workshop