Nine months ago, Dr. Sandrine Han suggested that I should check out Learning Creative Learning created by Lifelong Kindergarten at MIT Media Lab.

I hesitated for a moment because I was not sure if I would be able to complete this open online course. After all, the average completion rate of MOOC courses is about 15%. To my surprise, not only did I finish the entire course, but also go back and review some of the articles and resources provided by Mitchel Resnick and his lab team.

Learning Creative Learning is now officially a source of inspiration for me. The course materials are fun to read, the course structure is well-designed with 6 easily digestible modules, and the principles and strategies can be applied to any discipline at any school or university. I would recommend every educator to take the course if time allows.

However, if you do not have the time to finish the entire course, these are the things I would like to share with you:

- The spiral process of creative learning

- The core concepts of 4P’s: Project, Passion, Peers, and Play

- Strategies to foster creativity

1. The Spiral Process of Creative Learning

In the first chapter of his most recent book Lifelong Kindergarten: Cultivating Creativity through Projects, Passions, Peers, and Play, Mitchel illustrates the spiral process of creative learning: an iterative process when someone engages in a creative activity.

Creative Learning Spiral (Courtesy of Mitchel Resnick)

Creative Learning Spiral (Courtesy of Mitchel Resnick)

According to Mitchel, IMAGINE is usually the first step, followed by actions to CREATE things. PLAY refers to a stage where people experiment or tinker. SHARE create spaces for collaboration and peer feedback. Reflect basically means “how might we improve,” typically guided by a teacher or facilitator.

As a spiral process, the creative learning cycle is iterative in its nature. That means students need to try out different ideas and approaches to solve problems and improve their solutions. In order to support the creative learning process, Mitchel introduced 4P’s: Projects, Passion, Peers, and Play.

2. Projects, Passion, Peers, and Play

Projects

In chapter 2, Mitchel suggests that project-based learning is critical because it is the key to fluency, a similar concept to mastery.

“… When you learn to write, it’s not enough to learn spelling, grammar, and punctuation. It’s important to learn to tell stories and communicate your ideas… Imagine trying to learn to write just by working on crossword puzzles. It could improve your spelling and vocabulary, and it could be fun, but would you become a good writer, able to tell stories and express your ideas fluently? I don’t think so. A project-based approach is the best path to fluency, whether for writing or coding.”

Mitchel also argues that learning by doing is not enough. Students should engage in learning by making, which is the process of designing, building, and creating something:

“in the culture of the Maker Movement, it’s not enough to do something: You need to make something. According to the maker ethic, the most valuable learning experiences come when you’re actively engaged in designing, building, or creating something—when you’re learning-through-making.”

The idea of learning by making can be challenging to many of us. If you are wondering where to start, I would suggest thinking about these questions:

- How do your current activities, feedback, and assignments support or do not support the “making” process?

- How can you create authentic projects that support the acquisition of 21st-century skills?

- And more importantly, are you willing to try out new approaches?

Passion

In chapter 3, Mitchel introduces the idea of “wide walls” building on Seymour Papert’s concepts of “low floor” and “high ceiling.” “Low floors” means technology should provide easy ways for novices to get started. “High ceiling” means technology should also provide ways for people to work on increasingly sophisticated projects over time.

According to Mitchel, “wide wall” adds that technology should support a wide range of different types of projects because people have different passions. He also suggests that passion leads to a phase of immersion in learning.

“Developmental psychologist Edith Ackermann described the process in terms of diving in and stepping back. When people work on projects they’re passionate about, they’re eager to dive in and immerse themselves. They’re willing to work for hours, or longer, and hardly notice that time is passing… But it’s also important for people to step back and reflect on their experiences. Through reflection, people make connections among ideas, develop a deeper understanding of which strategies are the most productive, and become better prepared to transfer what they’ve learned to new situations in the future. Immersion without reflection can be satisfying, but not fulfilling.”

He points out that we need to encourage “hard fun” instead of believing the misconception that students want learning to be easy.

“Too often, teachers and educational publishers try to make lessons easier, believing that children want things to be easy. But that’s not the case. Most children are willing to work hard—eager to work hard—so long as they’re excited about the things they’re working on.”

Although it is obvious that people learn the best when they are led by passion, it is not easy to implement when students just need certain courses in order to complete their degrees. However, whenever possible, it is our job to create space for flexibility and agency that ignite passion.

If there is not much you can change in your course content, how about giving students choices to decide the format of their assignments? If they enjoy creating videos, can they submit a video instead of a writing assignment? And even before that, do your students know that they can talk to you about their interests or preferred ways of learning?

Peers

Mitchel suggests that we need to shift from think-it-yourself to make-it-together.

“This approach is more aligned with the needs of today’s society, where almost all jobs require collaborative effort, and the most important social issues require collective action.”

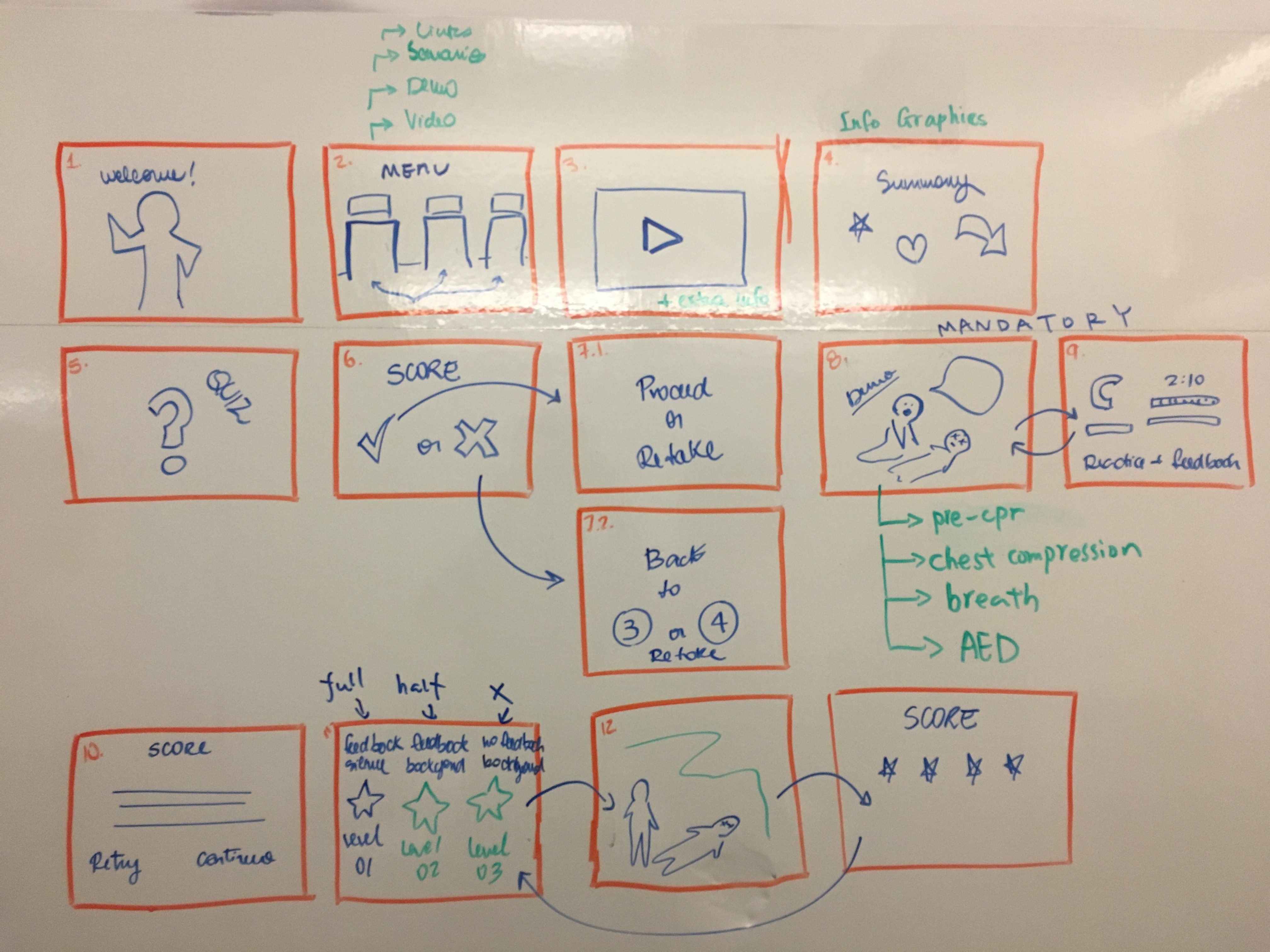

With peers, students collaborate with and learn from each other to create prototypes and artifacts. They seek for team members offline and online and develop communities by themselves. These meta-cognitive strategies enable them to become more self-sufficient.

But how should we support this? In chapter 4, Mitchel addresses it by discussing the shifting role of teachers:

- Catalyst: The best way for a teacher to provide a spark is to ask questions. By asking the right types of questions, a teacher or mentor can catalyze exploration and reflection, but the learner remains that active agent, in charge of the activity.

- Consultant: The goal is not to “deliver instruction” or “provide answers,” but to understand what people are trying to do and figure out the best way to support them.

- Connector: An important part of teachers’ job is to connect learners with other people who they might work with, learn with, and learn from.

- Collaborator: Teachers or mentors don’t simply provide support or advice. They work on their own projects and invite people to join in.

Play

Why is play even relevant or essential? In chapter 5, Mitchel explains that play helps students to explore the unknown and the uncertainty.

However, not all types of play are equally valuable. Citing work from Marina Bers, he agrees that there is a difference between playpen and playground.

“The playground promotes, while the playpen hinders, a sense of mastery, creativity, self-confidence, and open exploration.”

“Playpen” indicates limitations and restrictions, whereas “Playground” is open and encourages social interactions. With that, he suggests that the tinkering process combines the value of “playing” and “making.”

“The tinkering process is messier. Tinkerers take a bottom-up approach: They start small, try out simple ideas, react to what happens, make adjustments, and refine their plans. They often take a meandering, circuitous path to get to a solution. But what they lose in efficiency they gain in creativity and agility. When unexpected things happen and when new opportunities arise, tinkerers are better positioned to take advantage.”

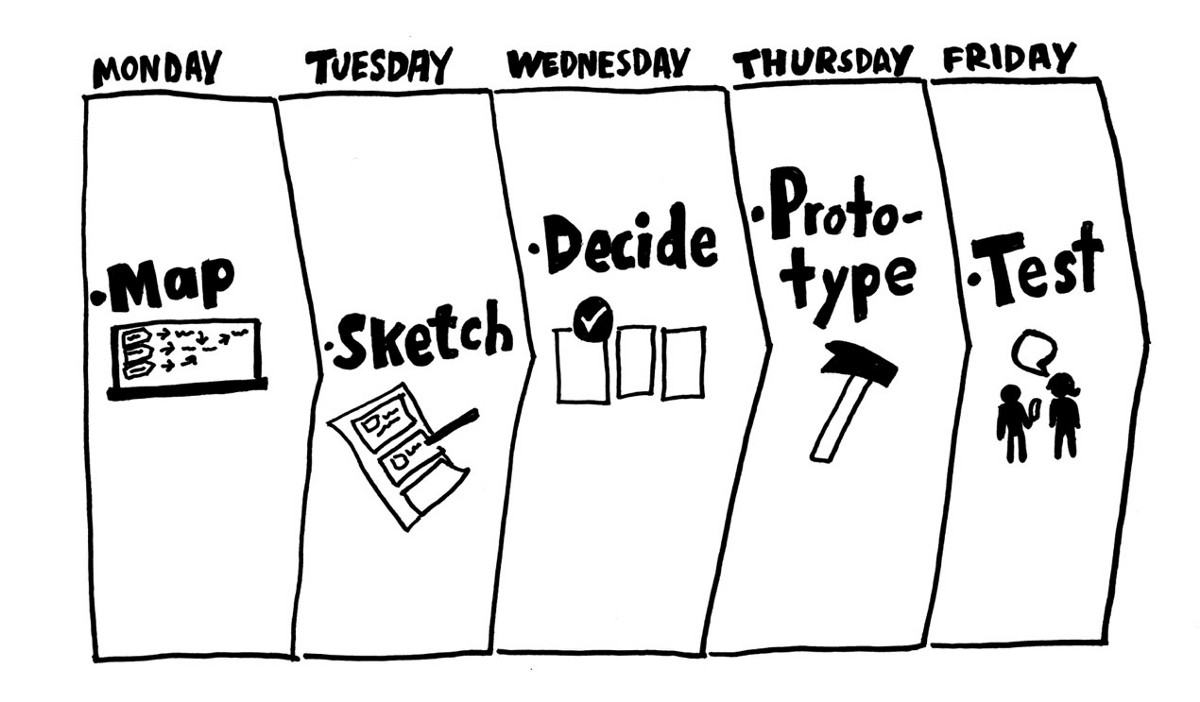

Tinkering is inherently an iterative process, similar to the process of design thinking.

“Tinkerers believe in rapid prototyping and iteration. When working on a design project, they build something quickly, try it out, get reactions from other people, then make a new version— over and over.”

In order to cultivate creative thinkers, he cautions that teachers need to understand that step-by-step instructions should be a stepping stone, not a final destination. Teachers also need to encourage students to try out different approaches and styles so that they can switch strategies as situation warrants.

3. Strategies to foster creativity

In chapter 6, Mitchel lists 10 tips for parents and teachers to support the development of creativity based on the spiral process of creative learning. You may also find the 10 Tips here.

Contextualizing Learning Creative Learning for learning design in general, I think there are a few things we could implement effectively with some reasonable efforts:

- Low floor: A course should be designed in a way that is fun and provides a strong sense of achievement at the beginning. For example, you could gamify your first class by introducing a trivial game with a leader board, and everyone wins something.

- High ceiling: When possible, learning tasks should be designed with a gradual increase in difficulty. A simple way to increase difficulty is to provide less support or aids. For example, your students may be provided step-by-step instruction at first. As the course progresses, students are asked to perform a task with less or no instructional aids. Sometimes it just means you talk less.

- Wide wall: Consider the needs and interests of your students. Give students chances to choose projects or assignments. Empower them to figure out a topic they are interested in within the subject. An example I provided previously is to think about the format of your assignments, can students submit video assignments rather than writing assignments? Are they given the opportunities to discuss with you about their preferred ways of learning?

- Allow play and mistakes: High-stake assessments do not usually afford mistakes. Consider “drop the lowest grade” if you have multiple projects in one course so your students could experiment different approaches, or consider allowing students to submit assignments a few more times to make improvements (iterations) based on formative feedback they receive.

- Room for unknown: Use worked-out examples with purpose. Depending on your objectives, you may provide step-by-step instruction first, or you could give students opportunities to imagine and explore the possibilities of solving problems first. The key is that students need to understand that unknown is constant in the real world and the only way to deal with it is to try different approaches

- Build the habit of reflection: Establish a process for reflection. Provide opportunities and tools for your students to reflect as an individual and as groups. A simple tool like KFC (keep, fix, change) will make the reflection process much easier for new students. Also, encourage your students to document their process and iterations for reflection.

So, how about some creativity with your course design and teaching practices?

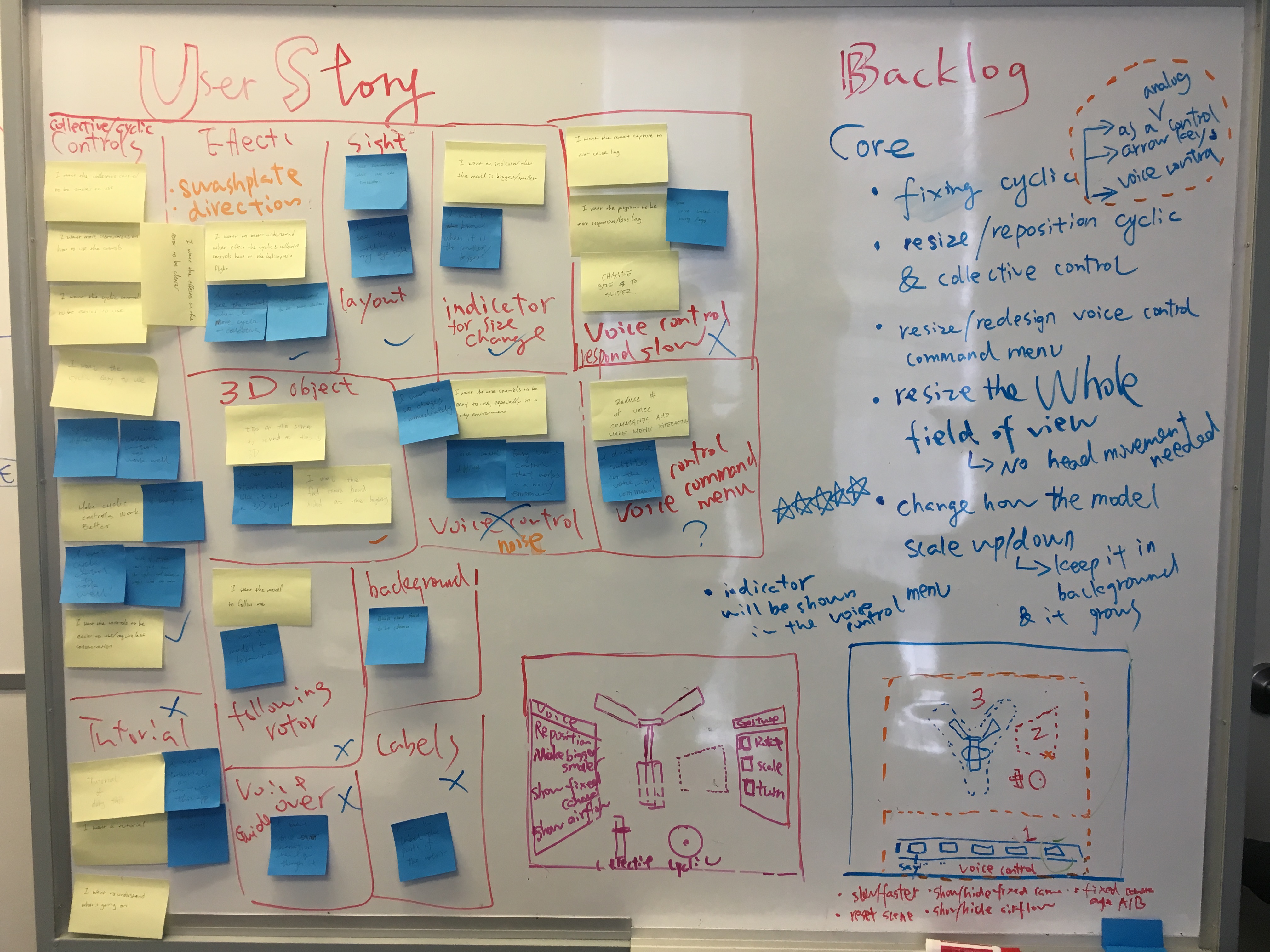

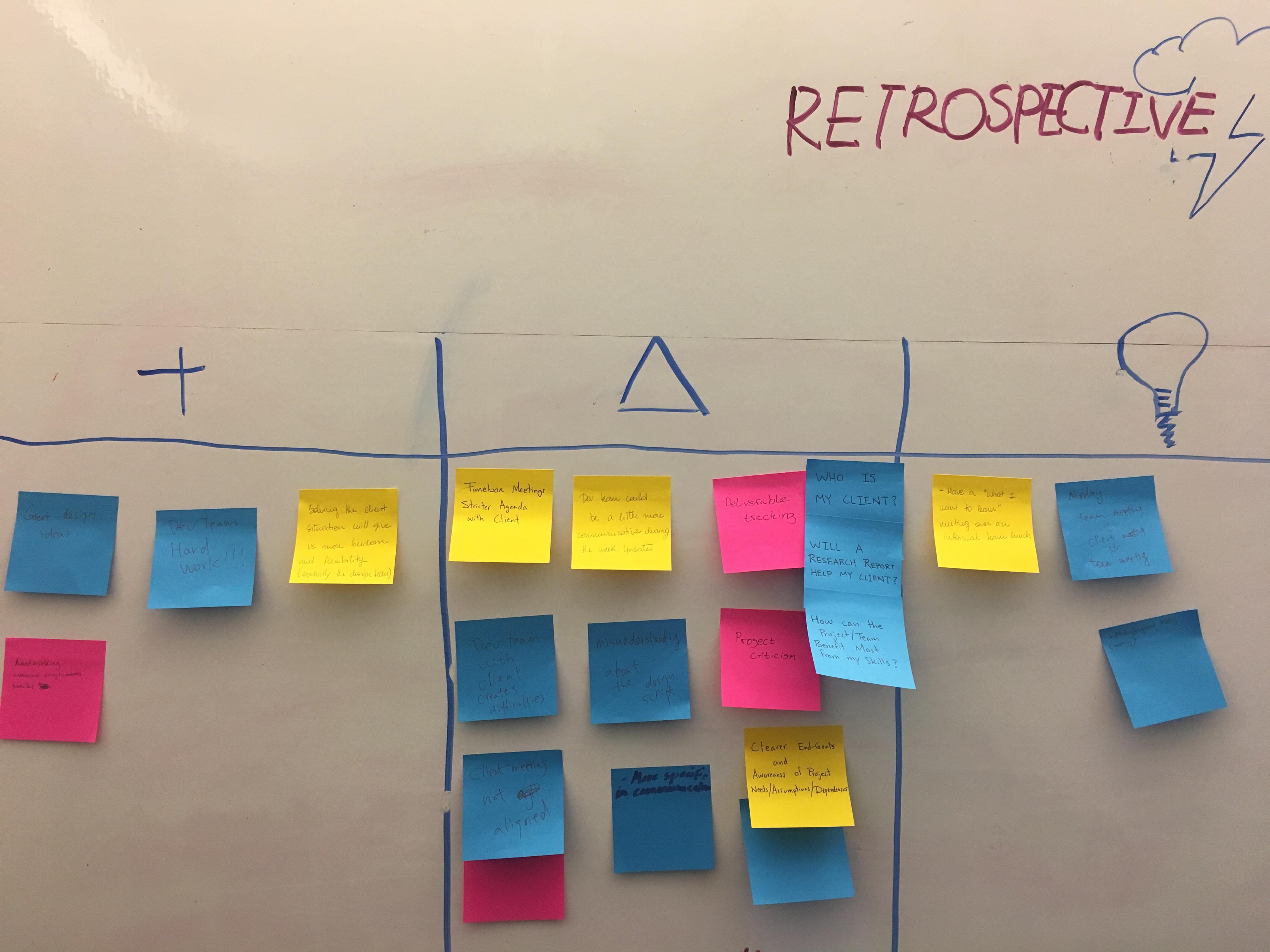

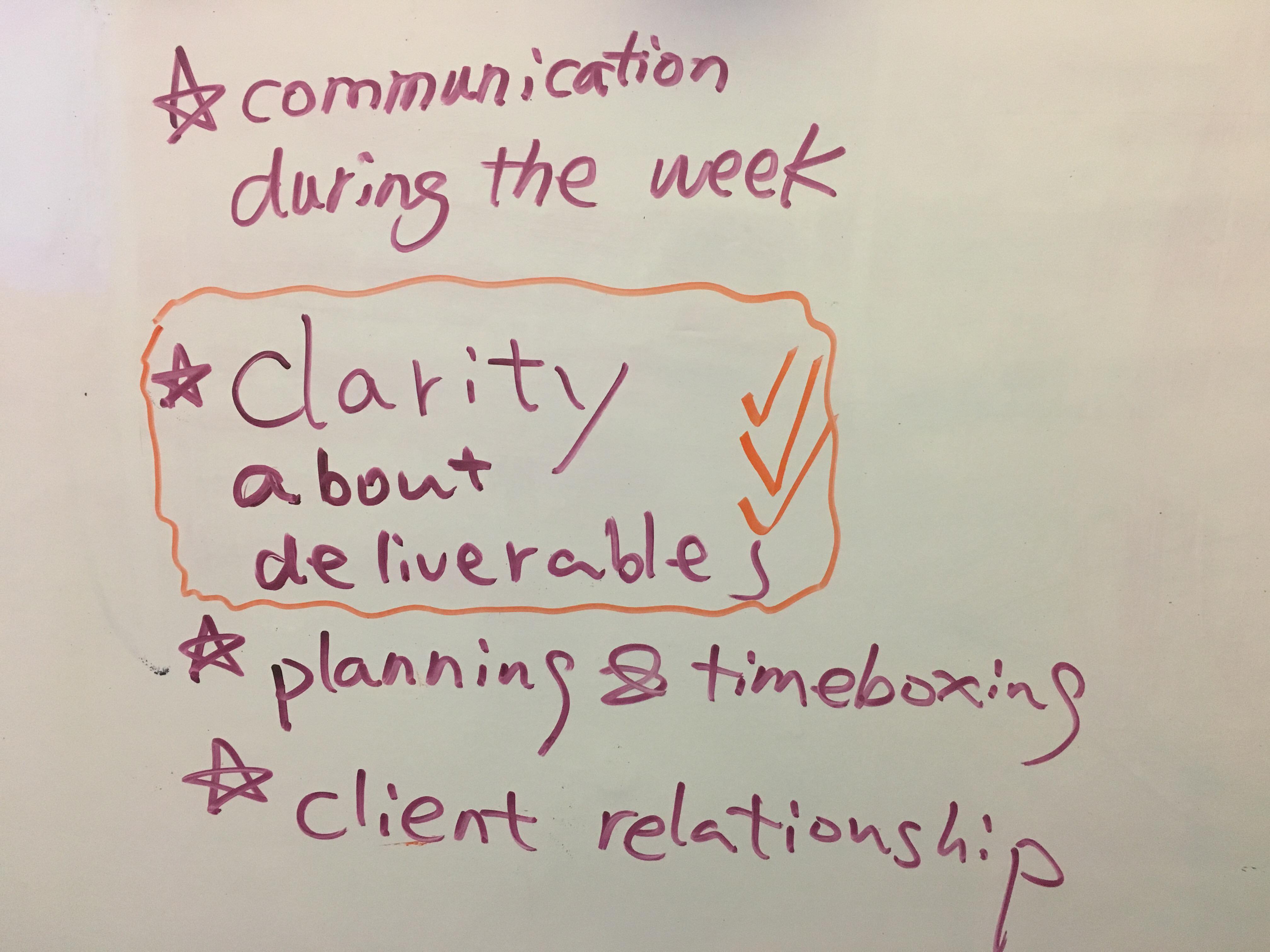

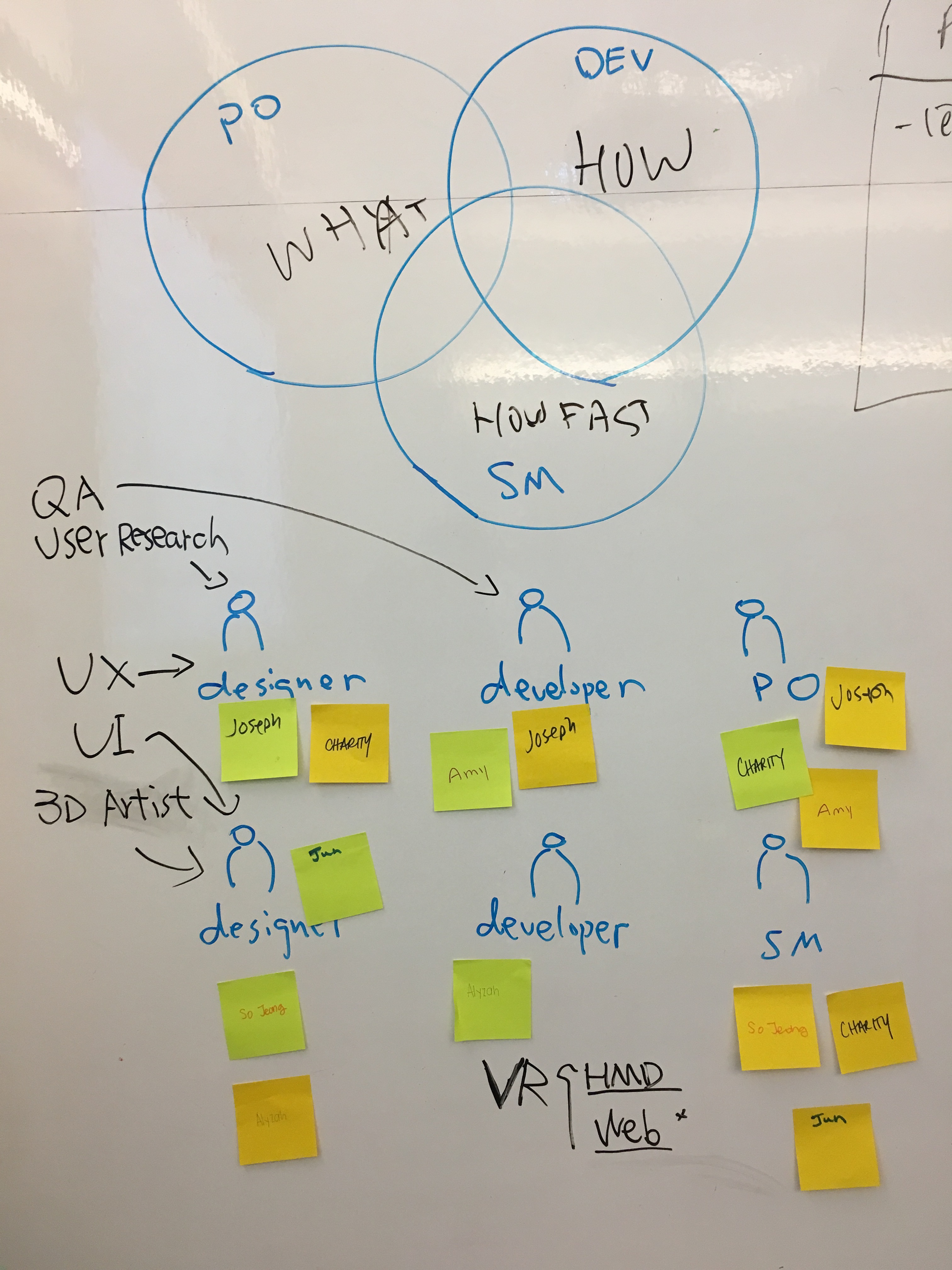

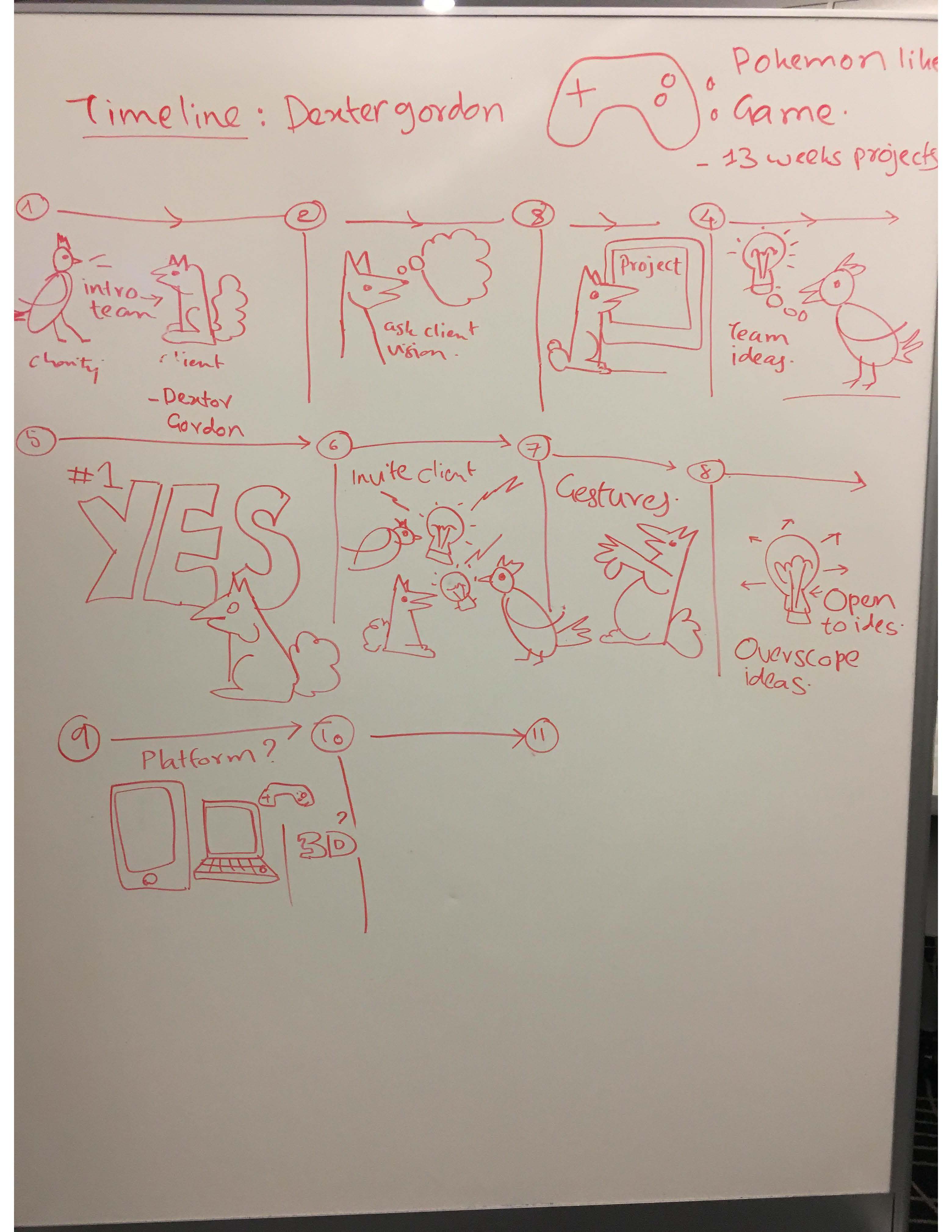

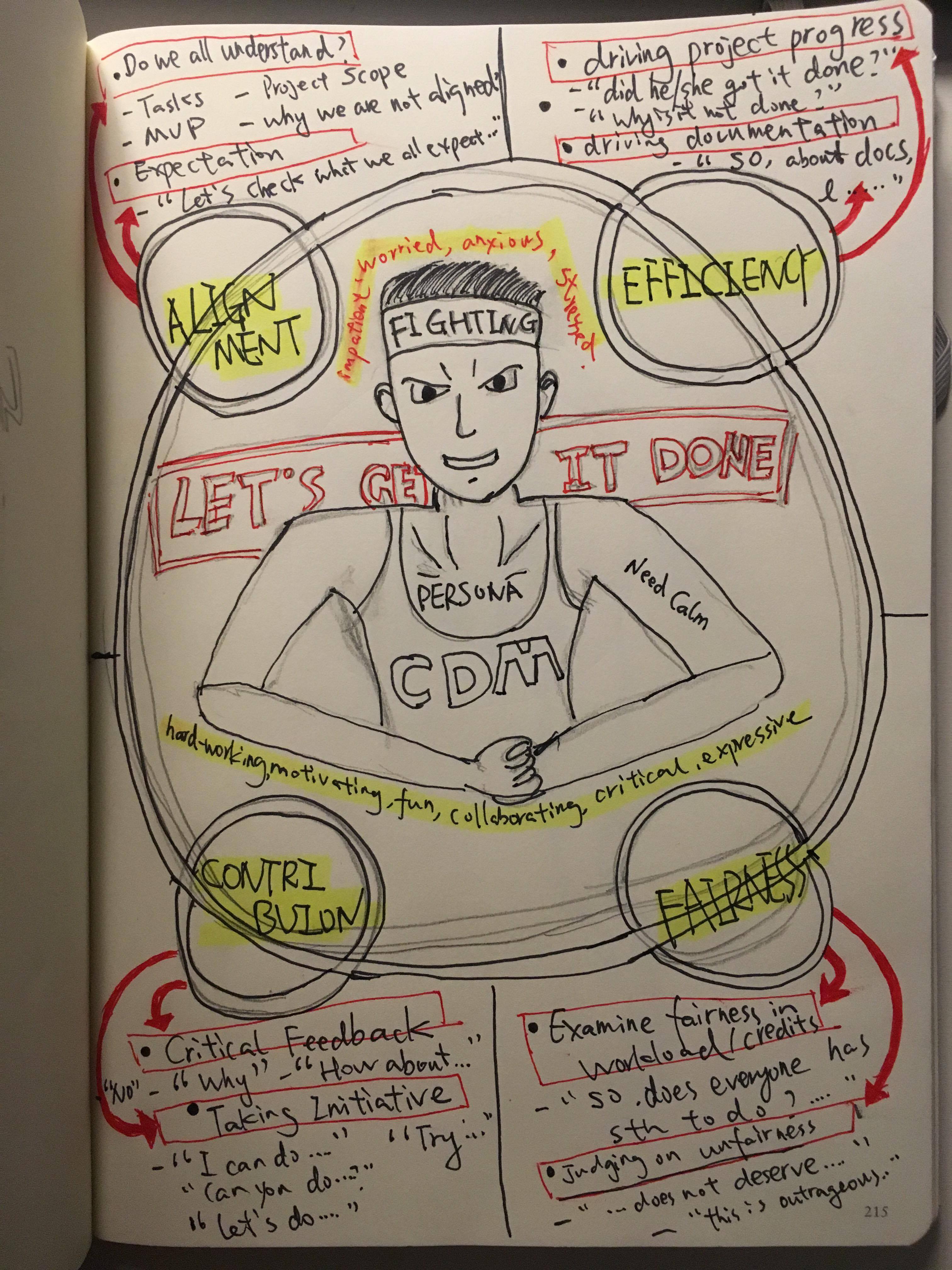

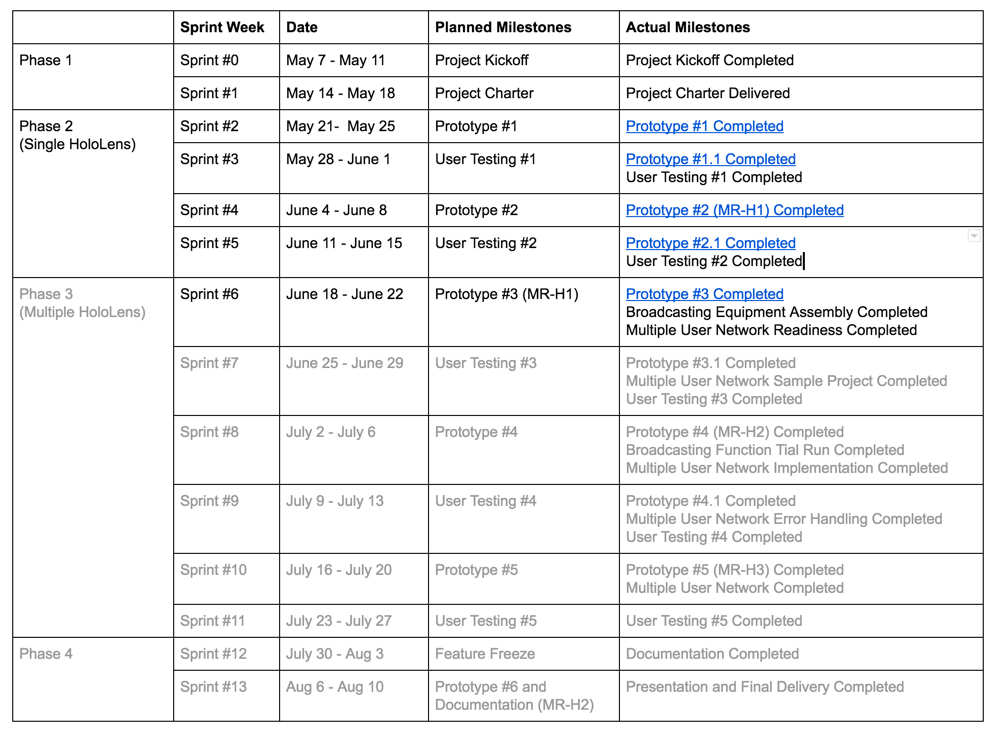

(Credit: Junsong Zhang, Project Manager)

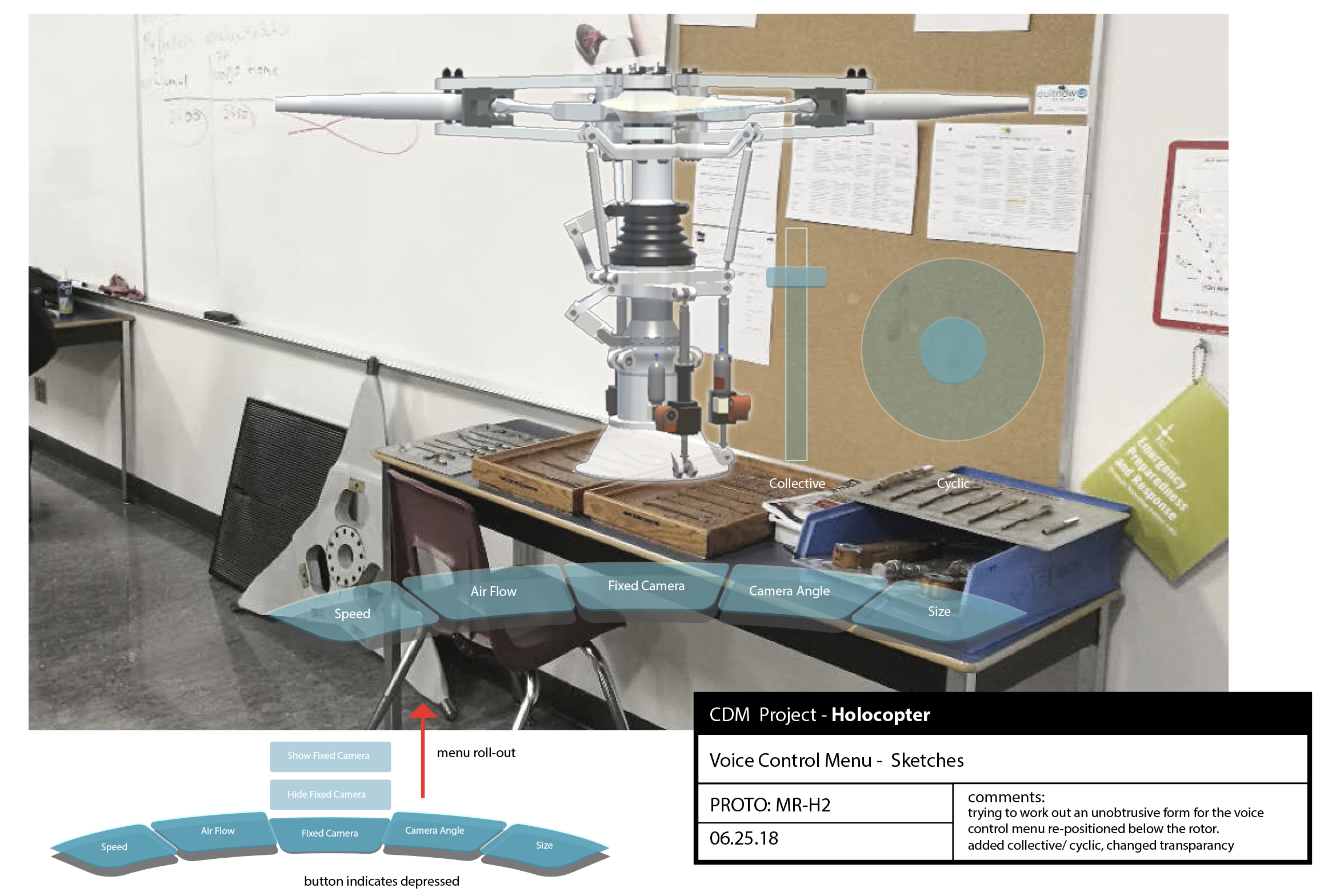

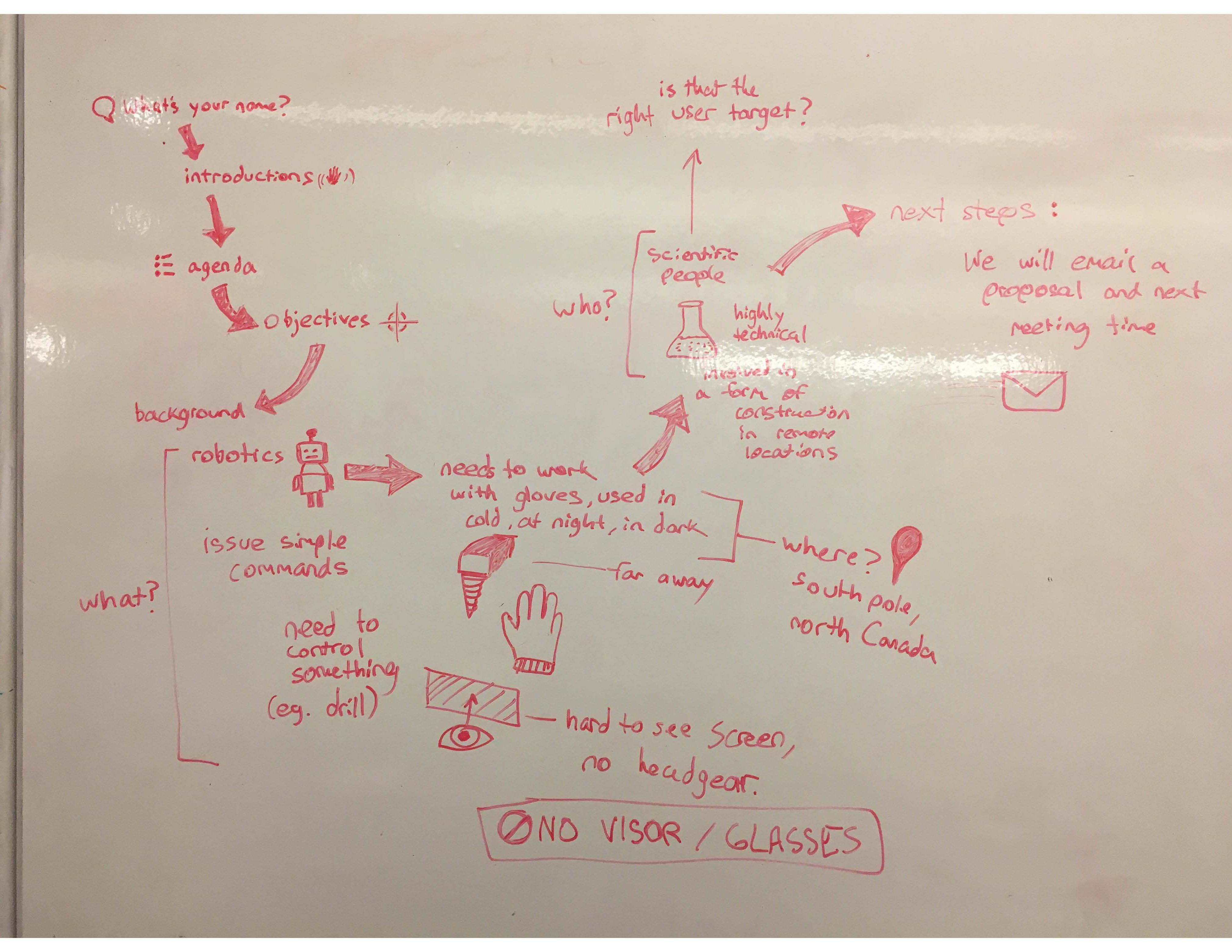

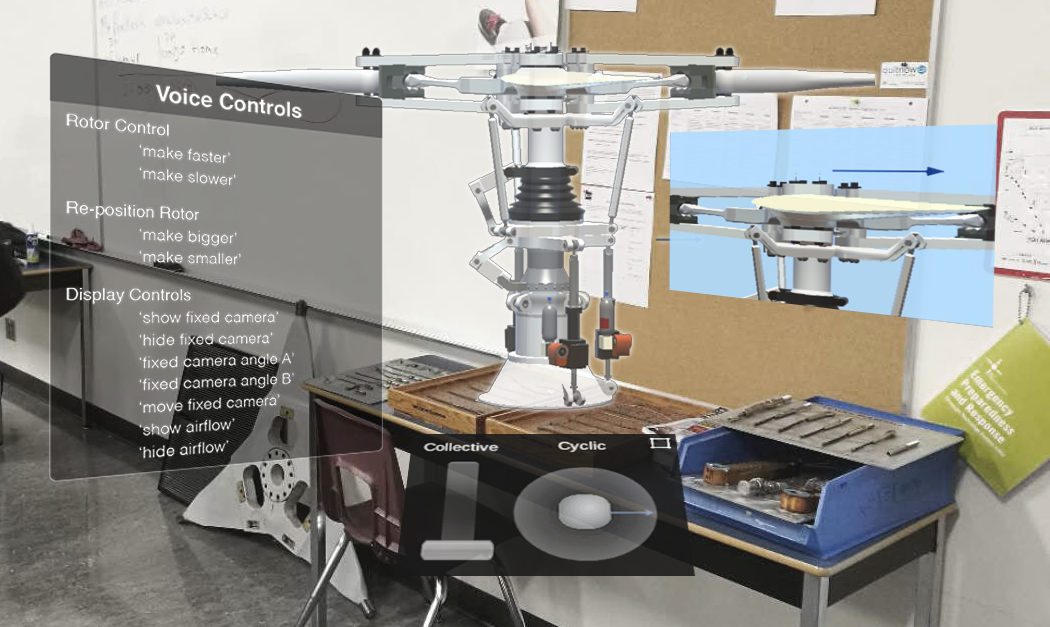

(Credit: Junsong Zhang, Project Manager) (Image Credit: John Bondoc, UX/UI Designer)

(Image Credit: John Bondoc, UX/UI Designer)