Write a short story that describes your sense of home; write about the values and the stories that you use to connect yourself to, and to identify your sense of home.

My dad, bless him, likes to proudly inform people that our ancestry is “British-Canadian on one side, and Canadian-Canadian on the other.” By that he means that a genealogy test showed that, on one side of the family, I have English ancestors dated as having lived in Canada for centuries. I’ve tried gently reminding him that being descended from a long line of British tobacco farmers is not necessarily something to be proud of – nor, I’ve tried gently escalating to, does that make us ‘Canadian-Canadian’ so much as more liable to have had a direct ancestor take more active action into forcibly removing the country’s actual first inhabitants from their land, homes, and families. But, well-intentioned and actually quite eloquently aware of Indigenous and First Nations issues as he is, my dad is still apt to bust out this remark whenever given the chance. It’s a story he grew up with, after all, and a pretty hard one to uproot. His whole life, to him, this has been ‘his country,’ and ‘his home.’

Home, for me, has always been a much smaller concept, usually involving four walls and a family within them. That good ol’ fashioned contrivance is a boat that’s been rocked a fair few times throughout my upbringing, and probably helps explain why I initially took it so hard when my parents divorced in my early teens. In my eyes, as I hopped between houses and parental units, I wasn’t just grieving – I was homeless.

For a few years, I scrabbled to hold onto any dregs of my initial sense of home I could. I declined moving away for my undergrad, instead attending one in my hometown – a mid-sized city near Toronto, Ontario. I lived with my family, hung out with the same friends I had for 10+ years, religiously revisited the same books, movies, and even childhood cartoons I had always watched (to this day, the opening hair metal guitar riff of the 1994 Spider-Man cartoon is about as indicative of a deep-rooted sense of home to me as anything). Change became an ugly word to me. All in all, I did my (unconscious) best to puff up the ship in a glass bottle that was my life. For a while, it worked pretty well, too.

In my early twenties, I took my first major solo trip, spending months backpacking around Australia and New Zealand. It was a foundational experience for me in a number of ways, none the least being away from home for so long. On one hand, travelling abroad reified a number of (largely positive) Canadian stereotypes for me – other backpackers would initially bristle in suspicion when I talked to them, but then brighten and relax considerably when I mentioned I was Canadian (you could practically smell the whiff of ‘Phew! Not American’). Being away from Canada (from home?), I started to feel my first real rumblings of pride to be Canadian reinforced by new friends from around the world, and the itch of home meaning not just a house, not just a city, but a country, for the first time ever.

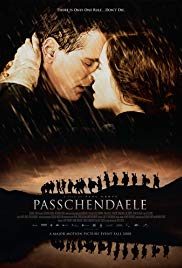

Emboldened, I sought out other Canadians in each hostel I stayed in with particular enthusiasm, seeking to further reinforce the now steadily conflating sense of ‘self,’ ‘home,’ and ‘Canada.’ In Queenstown, New Zealand, I came across a couple of other Canadians, who were equally keen to buy into the national jingoism. We spent a night together at the hostel we were staying at sharing stories of home (they were from BC and had never met an Ontarian before), our thoughts on being abroad (to them, generally a list of things they thought Canada had done better – umm, okay? thought young, non-confrontational me). As the conversation began to wane, we resolved to watch – what else? – a good ol’ Canadian movie, the Paul Gross war film Passchendaele.

Passchendaele (dir. Paul Gross, 2008).

Halfway through the movie, a thought catapulted across my head.

I was bored to tears.

No offence to Paul Gross (I’m not a fan of war movies – too much entrenched, largely harmful ideology – but, to me, this one was a bit hokey and generic, but earnest and largely harmless) – it was more the emptiness of the entire scenario that rang like a bell in my head. I realized I had had better conversations with backpackers from Germany than my fellow Canadians, and that the contrivance of the entire situation rang false to me. I was trying to fight homesickness by hanging out with fairly uninteresting (and a bit arrogant and catty?) people who just happened to come from the other side of the same gigantic land mass with arbitrary national borders as me, to whom the beauty and wonder of the other country we had the privilege to explore seemed completely lost on. I sullenly finished the movie (I am nothing if not a completionist), and quickly excused myself to bed.

I hold this experience in my heart as one of the first times I deeply realized that home need not be a particular point on the map, or set of four walls, so much as a feeling of belonging and deep peace. Over time, that feeling steadily morphed into a subtle, gentle magnet pointing elsewhere. Pointing west. Moving across the country to Vancouver was emotionally difficult for me, but never something I doubted. Home, I think I knew in my heart, had picked up and rumbled across the land. And I knew I’d better gather my stuff and follow, if I knew what was good for me.

It didn’t take much time before I was using the word ‘home’ to describe Vancouver rather than Ontario, even if the stumble between the two always struck me as poignant. Ontario was ‘home’ (ie: hometown – a place to see family, old friends, and bathe in memories), but Vancouver was home. A place that felt right for me to be in. A place with mountains and ocean, a place where my brain could be free to discover new wrinkles of thought and possibility. A place where I could properly learn the history of the country I’d grown up in, including the less jingoistic stories of barbaric colonialism that would make ‘early-twenties-New-Zealand-dwelling-Passchendaele-watching’ me cringe in shame and disgust (for part of that home growing up had been a tidy bubble of ignorance in regards to the people who walked these lands before my ancestors did; a bubble from which I could also proudly declare myself ‘Canadian-Canadian’ without an ounce of context). A place where I could become wise, and at peace, and reinvent my adult life in the shadow of mountains. A place where I could be me, not running away from the past, but building off of its scaffolds, like a Jenga tower.

Almost.

I spent the better part of my first year in Vancouver feeling agonizingly homesick, even if every time I went back to Ontario (which I was already, in my head and out loud, calling ‘home,’ not home), I felt even more out of place. I felt like I walked around like a ghost, not fully belonging here, and definitely not belonging there. I had tried so hard to graft a sense of home onto this beautiful place I’d moved to, but it still wasn’t quite right.

Since then, I’ve retreated my parameters a little bit, arguably even past the ‘home-is-four-walls-and-a-family’ model. I’ve made and lost friends and communities, fallen in and out and back in love with Vancouver (as beautiful as it is, it’s hard to get long-term invested in a city so claustrophobically expensive to inhabit), reconciled my always tenuous sense of patriotism with a national history I’m hardly proud of, and grown oodles as a person. For someone who’s always been so staunchly, stubbornly rooted and resistant to change, I’ve even generally carved out a sense of ‘home’ that, while I’m still pretty darn far from nomadic, I feel much more comfortable that I can pick up and take with me like a hermit crab.

(The secret is as cheesy as it is heartfelt, so brace yourselves!)

Home for me now means you can hold on the four walls. Home now just means family. And mine remains a pretty dispersed one, with members strewn across the country and the planet. But I’ve found a stable, abiding core in my life partner. For years, home meant living with her and loving her in my modest, messy apartment with her. Now, since talk of moving about in BC, or even elsewhere on the planet, home just means her. I may have always rolled my eyes at the expression ‘Home Is Where Your Heart Is,’ but it’s never resonated as much to me as it does now. Home can mean Ontario, or BC, or Canada. It can mean a particular dwelling space. But I now see all of those things as a conduit to the people (oh fine; mostly person) who I most want – nay, need – to spend my time with. Who bring out the best in me, and finally give me that feeling of belonging and deep peace. With that, home isn’t a where. It’s a who.

And that gives me more comfort than anything else ever has.

-KH

WORKS CITED

Alini, Erica. “Here are the most expensive – and cheapest – cities to rent in Canada.” Global News. Web. Accessed on January 28, 2019. https://globalnews.ca/news/4706857/cmhc-rental-market-report-2018/

Passchendaele (film). Dir. Paul Gross. Rhombus Media, 2008.

Spider-Man (television show). Dir. Bob Richardson. New World Entertainment Films, 1994-1998.