I’m speaking tonight at a UBC Dialogue organized by the UBC Alumni Association on the topic of child poverty in BC. Here are some background notes.

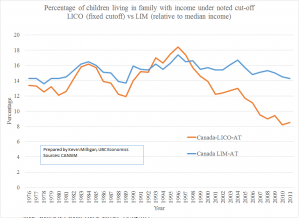

First, here is a graph using CANSIM data showing the proportion of children living in families below the Low Income Cutoff and the Low Income Measure. The Low Income Cutoff is a line that was fixed in 1992 and has only been updated for inflation since then. In contrast, the Low Income Measure depends on how the median family is doing in Canada. So, if the median is going up, the Low Income Measure cut off line also goes up.

The lines show that progress on child poverty depends on what measure you might like to use. The LIM line shows that low income families with children haven’t made any improvements relative to middle-income families over the last 35 years. The LICO line shows there have been some improvements in real inflation-adjusted income over the last 15 years.

Here are my notes that I will draw from for the discussion.

A. Opening statement

I’m an economist; a number-cruncher. What I’d like to contribute tonight is to listen to the ideas, compassion, and energy of everyone here and help to translate it into policies that have a proven record of success.

The policy area I’d like to address is child benefits. You might remember the old Family Allowance we had until 1992 that paid about $35 per month. Things have changed.

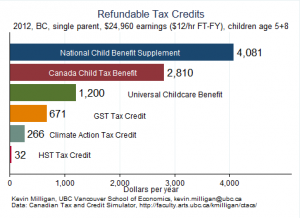

We now have an extensive system of child benefits, ranging from the Canada Child Tax Benefit to the Universal Child Care Benefit to the Working Income Tax Benefit to the increments a family gets for the GST credit. If you add all of these up, they make a tremendous impact on the lives of lower-income Canadians.

For example, if you take a full time full year single parent, with two kids, working at $12/hour, she might earn about $25,000 per year. In addition to this, she would be eligible for about $9,000 per year–or $750 per month–in child benefits. That is a very large 36% supplement on top of her wages.

If I can do one thing tonight, I hope I can increase awareness of this system and start a conversation about how to improve it.

B. Case for child benefits

Child benefits directly address the problem. Child benefits aim to alleviate low income in families with children by transferring more income to families with children–this is a very direct way to proceed.

Child benefits are very large. For a single parent with two kids working FT/FY at $12/hour the current package delivers about $9,000 ($750/month). This is a 36% increase over her wages alone.

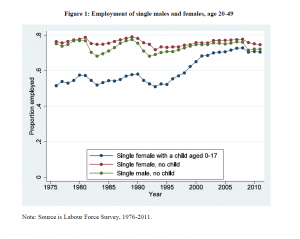

Child benefits help transition into paid work. Much evidence from many countries suggests that well-designed child benefit policies can provide a big boost for young parents entering the workforce. In the 1980s and 1990s, about half of single mothers worked. In the 2000s, this jumped by 40% in large part because of the new National Child Benefit Supplement. (See Milligan and Stabile 2007.)

C. Thinking critically about minimum wages.

There are lots of reasons people advocate for higher minimum wages, ranging from supporting workers’ rights, to gender equality, to improving the quality of jobs. But looked at strictly as an anti-poverty tool, I’m not convinced it is very effective.

Employment effects considered: Critics of minimum wage often exaggerate the negative employment impacts, but in my view they shouldn’t be ignored. The best recent evidence, from David Green at UBC and Pierre Brochu suggests that higher minimum wages do have an employment impact on teenage workers, but not for those over age 20. (See Brochu and Green 2013.) Also, it does matter where the minimum wage is relative to average wages. As that gap closes, research suggests the employment impact can be greater.

Minimum wage is poorly targeted: Most low-wage workers do not live in low income families. Most low-income families do not have minimum wage workers. Many minimum wage workers live in families that are middle or higher income. There may be good reasons to increase the minimum wage, but as an anti-poverty tool, it really is fairly poorly targeted. (See Campolieti, Gunderson, and Lee 2012.)

Impact on prices: the money higher wages for minimum wage workers have to come from somewhere. If those wages end up in prices of goods consumed by lower-wage workers, it’s not clear if who benefits. As one example, if McDonald’s puts up the price of hamburgers to pay for the higher minimum wages, and if these burgers are bought more by lower income people, the overall incidence might not be progressive. (See MaCurdy 2015.)