Assignment 3:7 – Write a blog that hyper-links your research on the characters in GGRW according to the pages assigned to you. Be sure to make use of Jane Flicks’ GGRW reading notes on your reading list.

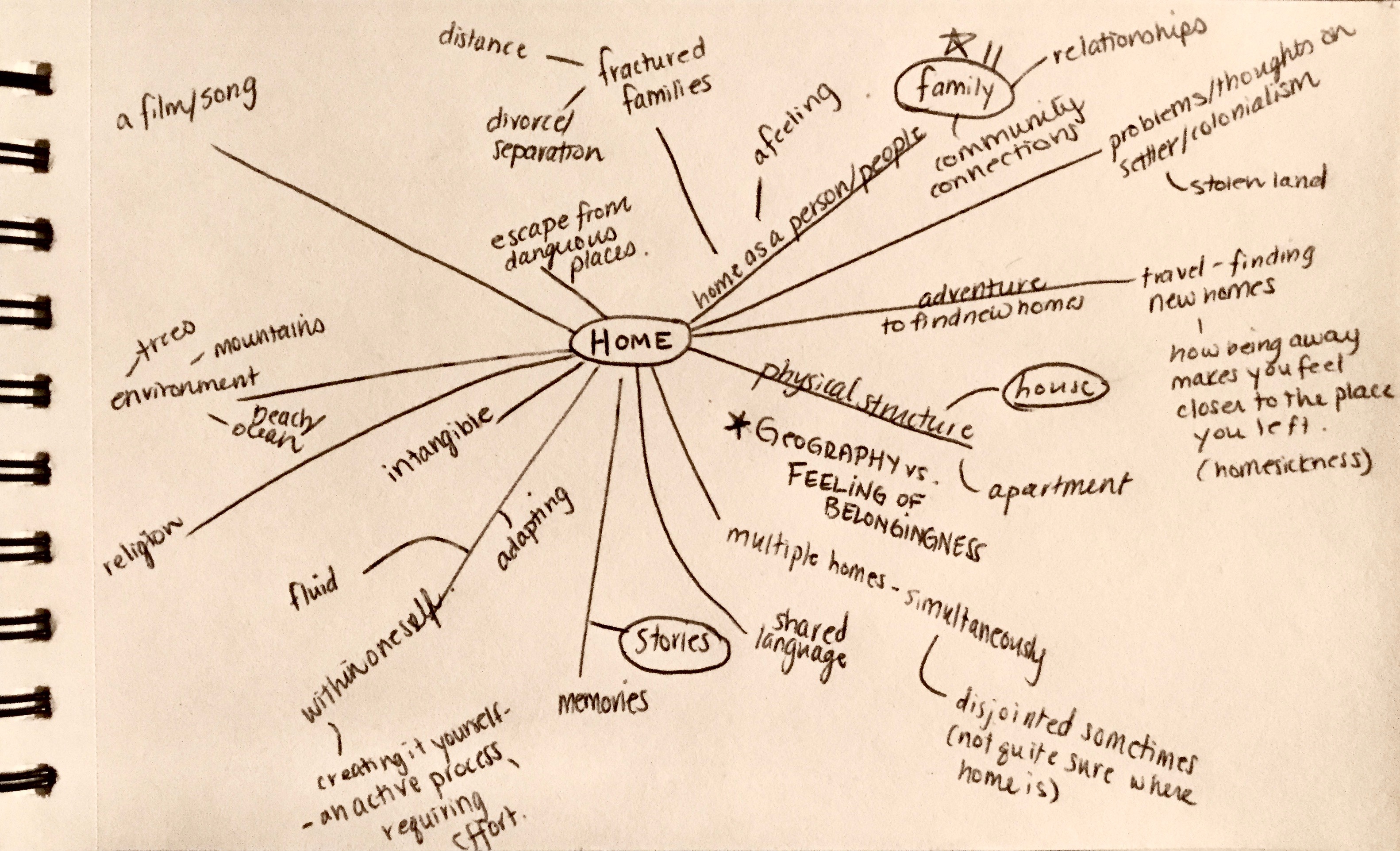

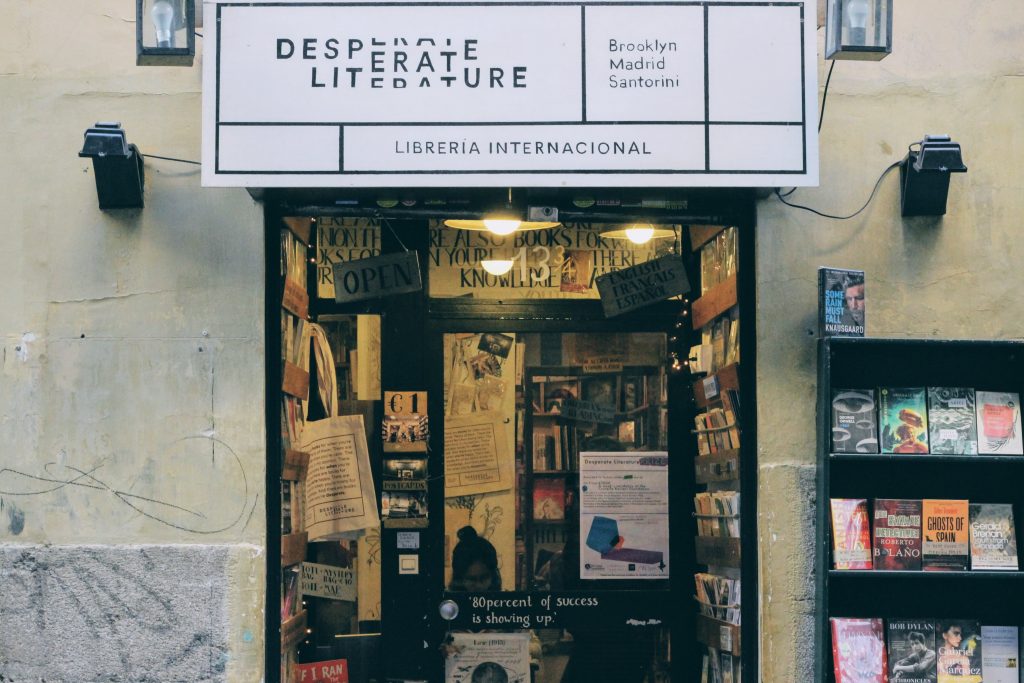

In “Coyote Pedagogy – Knowing Where the Borders Are in Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water,” Margery Fee and Jane Flick summarize the complexities of the novel when they deduce that “there is no reader of this novel, except perhaps Thomas King, who is not outside some of its networks of cultural knowledge” they go on to acknowledge that “every reader is also inside at least one network and can therefore work by analogy to cross borders into the others” (131). The beauty of King’s work is that he doesn’t answer questions, or give explanations, instead, he lays breadcrumbs throughout, compelling readers to continue and eventually find things out for themselves. I come to this book as a settler on Indigenous land; my background is European/Canadian and so my “basic general knowledge” covers primarily one of King’s “three distinct groups: Canadians, Americans, and Native North Americans” (Fee & Flick, 132). So, in this blog post, I’m exploring the allusions included on pages 1-3 and then 9-15 of Green Grass, Running Water (from here on referred to as GGRW) where we meet Coyote, Silly Dream, Dream Eyes, Dog Dream, that GOD, the Lone Ranger, Hawkeye, Ishmael, and Robinson Crusoe. King’s cyclical framework makes it difficult to definitively call this section “the beginning,” because it appears so often throughout the novel in different ways, but the first pages in this novel serve as an introduction to several important characters.

In the beginning…

Coyote: In my last blog post, I discussed coyote pedagogy, and part of my research for that involved learning about coyote as a symbol within Indigenous culture. I found Coyote’s introduction to be really in tune with their typically contradictory nature – that of the trickster who is both powerful and naive. Coyote states, “I am very smart” (2), tells the others that “Everything’s under control… Don’t panic” (2). From this snippet into his character, he appears initially as pretty authoritative (childlike, but with knowledge), and we see this contradicted later in the novel when his ignorance and naivety offers humour (for other characters and for readers).

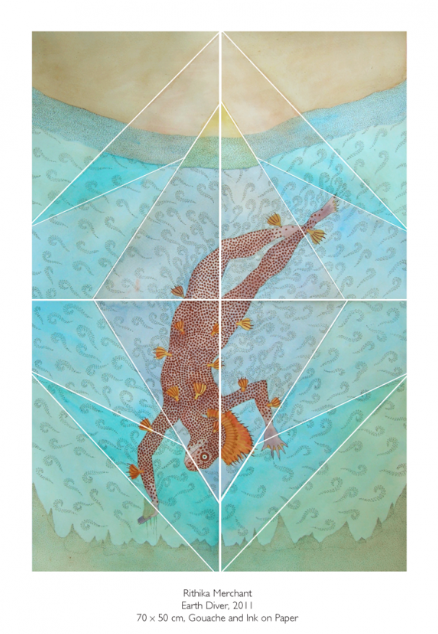

I decided to view Silly Dream, Dream Eyes, that Coyote Dream and Dog Dream as characters because I wanted to discuss how even with something so seemingly simple naming characters, King resists categorization. Within many Indigenous cultures, dreams are interpreted and judged differently than in Western culture. Jean-Guy A. Goulet, in his article “Dreams and Visions in Indigenous Lifeworlds: An Experiential Approach” explains the difficulty in “contend[ing] with the fact that in these societies the distinctions familiar to the Western mind between the world of everyday life and the world of dreams are simply not drawn”; instead, ““the world of ghosts and spirits is as real as that of markets, though real in different qualitative ways” (173). He goes on to discuss the incompatibilities between Western culture’s “low tolerance of fantasies” and many Indigenous societies that find “well-developed traditions for inducing visions and/or lucid dreaming, traditions that are available to individuals as part of their social development” (173). When we read GGRW with an open mind, ready to cross borders and boundaries, we can more easily resist the urge to categorize and hierarchize what is and isn’t animate. Author Mel Y. Chen, in her book Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect draws the term animacy “from linguistics, where it refers to an entity’s degree of agency, awareness, sentience, liveliness, or mobility. Across languages, grammatical structures indicate speakers’ views about the animate and the inanimate. A simple example in English is the distinction between “he” or “she” and “it.” The latter is reserved for inanimate objects, so that calling a person “it” conspicuously performs his or her demotion on the animacy hierarchy” (Haynes).

“that Dog Dream has everything backward” (2)…

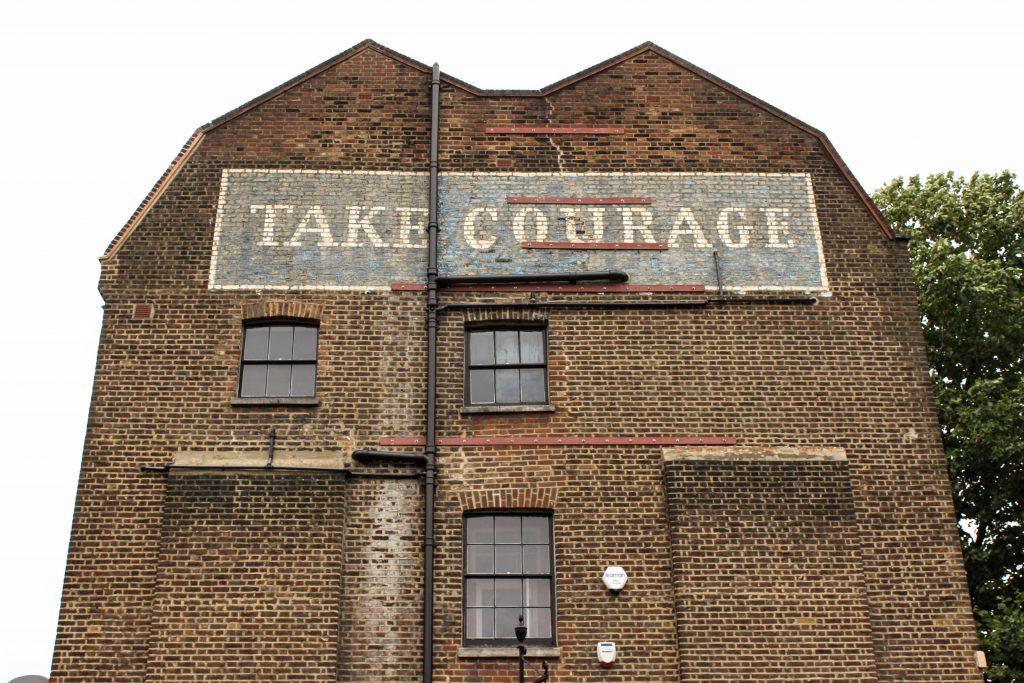

King’s humour and challenging of the Eurocentric status quo is evident from the first couple of pages. His allusion of that Dog Dream and that GOD to the Judeo-Christian version of God are powerful and illustrate right away that readers are going to have to suspend their preconceptions. We’ve discussed contradiction at length thus far in this course, and King artfully plays upon the dichotomy of Judeo-Christian vs Indigenous creation and faith.

The Lone Ranger, Hawkeye, Ishmael, and Robinson Crusoe

(Note: I’m going to refer to these characters using the he/him pronoun as they’re presented when they’re using these names for the purposes of this assignment)

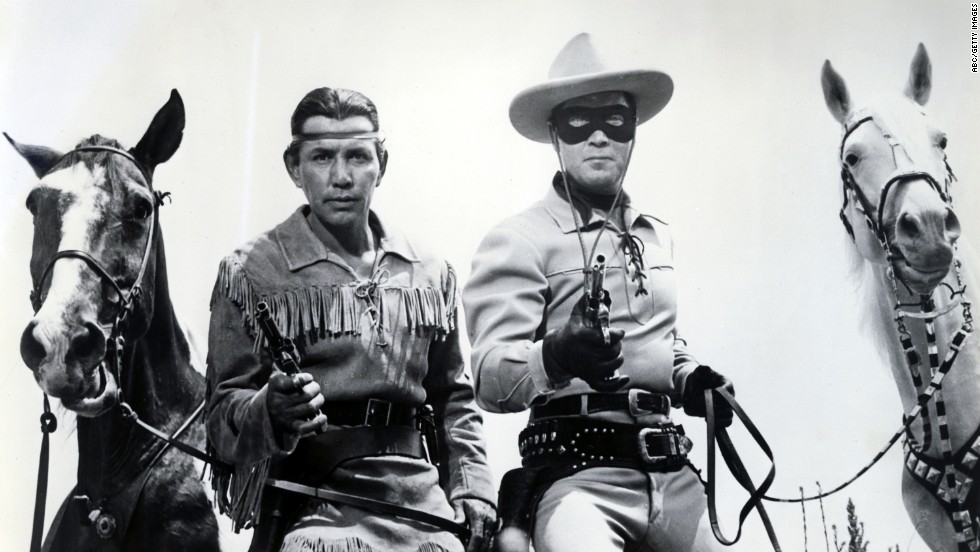

At first glance, these four characters represent Western ideals – colonization and the dominance of whiteness. They are all juxtaposed with variations of “the faithful ‘Indian’ companion” (Flick, 142). The Lone Ranger has long been a household name for American and Canadian families – he represents the strong male, fighting for justice alongside Tonto. Then there’s Hawkeye, whose counterpart is Chingachgook, Robinson Crusoe and Friday, and Ishmael and Queequeg. Each of these four characters is taken from diverse, but acutely American, origins. Peter Gzowski’s interview with Thomas King beautifully highlights the complexity of these characters:

TK: Oh, the four old Indians, yeah—the Lone Ranger, Ishmael, Robinson Crusoe and—

PG: Hawkeye.

TK: Hawkeye, right. Well, I wanted to create archetypal Indian characters. I wanted to create the universe again, and those characters—

PG: Tom?

TK: Yes?

PJ: The Lone Ranger’s not an archetypal Indian character.

TK: Well, actually, he sort of is, in some kind of a strange way, within North American popular culture, you know, you’ve got the Lone Ranger and Tonto, and you’ve got Ishmael and Queequeg, and you have Hawkeye and Chingachgook, and you have Robinson Crusoe and Friday, and these are all kind of—they’re not archetypal characters in literature, but they’re Indian and white buddies, I suppose. They’re kind of, not buddy movies, but buddy books, I suppose. But those are just the names that the old Indians have at the time that we meet them. In actual fact, these are four archetypal Indian women who come right out of oral creation stories.

Works Cited

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Lone Ranger.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 7 June 2015, www.britannica.com/topic/Lone-Ranger.

Flick, Jane. “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass Running Water.” Canadian Literature 161-162. (1999). Web. Mar 07/2019.

Haynes, Melissa. “Intersectionality Matters.” Reviews In Cultural Theory, 1 Sept. 2013, reviewsinculture.com/2013/09/01/intersectionality-matters/.

“Ishmael & Queequeg’s Friendship in Moby-Dick.” Study.com, Study.com, study.com/academy/lesson/ishmael-queequegs-friendship-in-moby-dick.html.

King, Thomas. Green Grass, Running Water. Harper perennial Canada, 2007.

“More than Just a Trickster: The Many Faces of the Coyote.” Fractal Enlightenment, 18 Jan. 2018, fractalenlightenment.com/40732/culture/just-trickster-many-faces-coyote.

“A Quarterly of Criticism and Review.” Canadian Literature, canlit.ca/article/peter-gzowski-interviews-thomas-king-on-green-grass-running-water/.