Write a short story (600 – 1000 words) that describes your sense of home; write about the values and the stories that you use to connect yourself to, and to identify your sense of home.

Home is a funny word, you know? Is it a place, or a person? Physical, tangible: that last step on the way to the basement that you trip on every time, ever so slightly? Or a feeling: fearless; incorrigible? Or perhaps a familiar smell, when you walk in the door, nine years old, haphazardly spilling wellie boots, mittens, sopping raincoat, and a half-opened backpack onto the floor as you breathe in Mama Bear’s oatmeal chocolate chip cookies?

Can you have just one, Home, I mean? When you happen upon a new one, does the old one get discarded? Or can you collect them, pocketing the good ones and turning away from the darker ones, questioning if they’d ever even counted?

There’s a place I call Home, and it moves, it moves within me, behind me, and beyond me. Like it’s waiting, waiting for me to make my next, almost always exceedingly deliberate move, but waiting patiently all the same.

First, Home was a house, a house in the prairies, on a tree-lined street, hipster adjacent to the somewhat more trendy Old Strathcona in Edmonton, Alberta. My neighbourhood was Hazeldean, a word which became the first “big” word I could spell without cheating, without whispering into the ear of my three-years-older sister for help with a letter here, a letter there. Home had a big backyard, filled lovingly with flowers by my gardener extraordinaire of a father. Flowers whose delicate petals became occasional casualties of the many soccer games I held there.

The inside of Home belonged to my mother, a sometimes stay-at-home mum, a sometimes nurse, an always baker. Home was cozy couches, always covered in cat fur; spilled grape juice, staining favourite dresses. Home was “the swoop,” an extravagant jump my sister and I invented, where we’d careen off one of our loft beds into a sea of pillows, coming quite close to peeing ourselves with laughter.

Home shifted as we got older. Home fractured as half of our previously inextricable unit moved to the west coast. Home adapted to this new way of being, together but apart. Home strengthened when its value became even more acutely obvious.

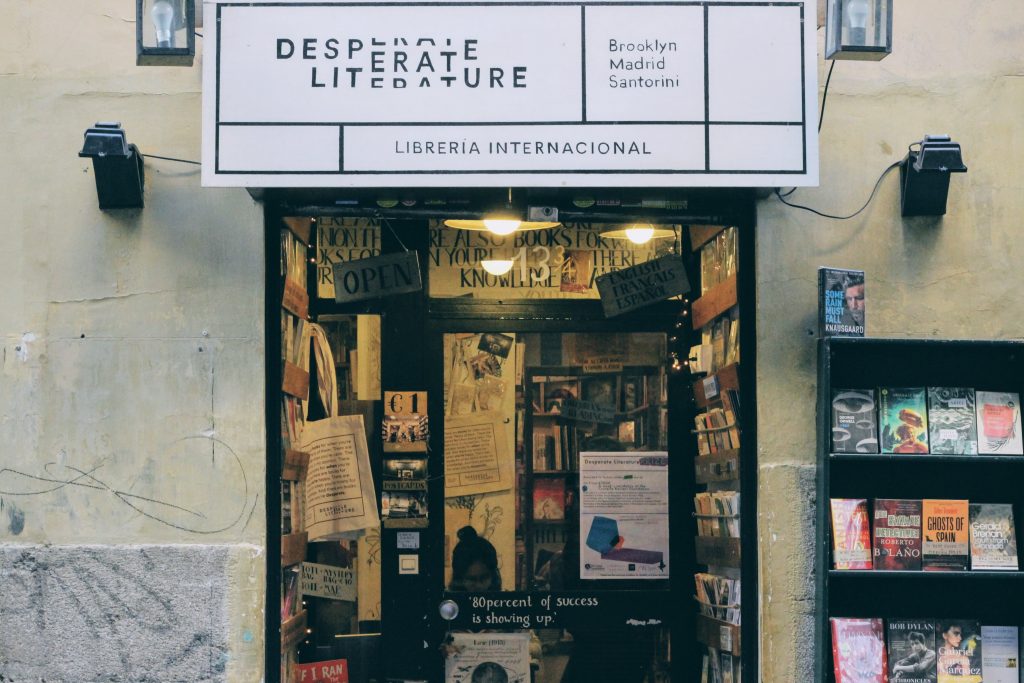

Then again, four years later, Home offered itself yet again, in a new, more exciting, more terrifying way. Home became a new country, a new way of living, an inviting blend of sangria, foreign tongues, ancient architecture; but above all, Home became a new feeling – independence.

Two years later, homesickness hit. Casually at first, like an ignorable fly, but then, with more meaning, a buzzing manifestation of all that I missed: my language, my family, my trees, my ocean. By this time though, Home was complicated. Home had become a new person; home had become a new, ecstatic, previously unfelt feeling. But Home had also become confusing, disjointed. Parts of Home were here. But parts of Home were there.

But you know what? The funniest thing happened. I got lucky. I got to bring this foreign Home, the Home I fell in love with, yet wanted to leave, home with me. Home took the form of a person, a person who somehow, and I still can’t fully comprehend how he did it, managed to encompass all that I loved about my adopted country, the bustling streets, the cantankerous bartenders, the always better tasting oranges, the unorthodox drivers, never not laying on the horn… And this new Home transformed me once more, extending its arms around me and pulling me close. Home illustrated again how truly enormous, yet somehow also infinitesimally small this planet really is.

Home became a person who gave theirs up, who traveled across oceans and prairies and mountains to preserve this newfound interpretation of the word. Home became a shared life, in a tiny, overpriced one-bedroom, blanketed with books, a kettle perpetually ready for more tea, an occasional meow, and a neverending lesson in Spanish.

Works Cited

Hyndman, Nikole. “5 Of the Most Inspiring Architectural Sites in Madrid.” IEUniversityDrivingInnovation, 29 Sept. 2018, drivinginnovation.ie.edu/5-of-the-most-inspiring-architectural-sites-in-madrid/.

“A Trip Guide to Old Strathcona, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.” To Do Canada, Todocanada, www.todocanada.ca/city/edmonton/listing/old-strathcona/.