A short documentary from VICE Canada looks at the recent forest fires in British Columbia and the role of climate change. There’s a terrific segment with UBC’s Lori Daniels on fire ecology and a few thoughts from myself on the big picture.

Author Archives: Simon Donner

A blast from El Nino’s past

The Canadian emissions quandary: Has this ship sailed?

Climate scientists often say stopping climate change is like stopping a supertanker. The ship has a lot of momentum, so you can’t just slam on the brakes at the last minute.

The analogy is referring to the physics of the climate system itself, but also holds true for the sources of greenhouse gas emissions. The technology exists to dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions but we can’t implement it all today over lunch.

In Canada, the emissions supertanker has been charging along despite repeated warnings of the iceberg ahead. After years without serious coordinated federal action, a promise to meet an ambitious emissions target, no matter how well-intentioned, no matter how grounded in scientific analysis, now looks unrealistic.

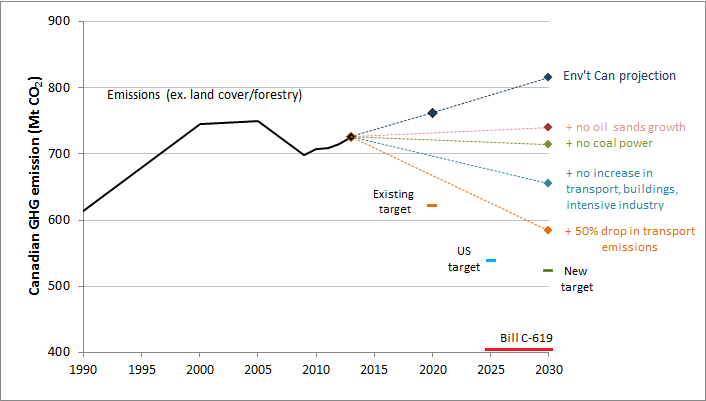

Here are the emissions since 1990 together with the Environment Canada projection to 2030, the various proposed emissions targets, and some coarse reduction scenarios.

Most analysts argue that the current government’s policies and plans are not close to sufficient to reach the existing target (17% below 2005 levels by 2020) or the new target (30% below 2005 levels by 2030). The emissions target from the “Climate Change Accountability Act” Bill C-619 (34% below 1990 levels by 2025, now 2025-2030), which the NDP pledges to reintroduce if elected, is even more unrealistic. Again, this is not about the scientific value of the target – Bill C619 would put Canada in line with the global goal of reducing emissions sufficiently by 2050 to avoid a high probability of 2 degrees C warming.

It’s clear from the emissions inventory that to reach even the less ambitious current targets, Canada would need to reign in emissions from the oil and gas sector and ramp up efficiency in transportation, buildings and other intensive industries (not to mention forestry – not included in this analysis). Many of the necessary innovations are possible, and some may be encouraged by resource prices and other global factors. It will still be difficult to meet the new 2030 target, let alone the ambitious and likely politically impossible Bill C-619 target.

After twenty years of political rhetoric, the plans are more important than the targets. Canada may not meet the proposed targets but it can at least make some progress and show a serious commitment to addressing climate change.

Has climate change played a role in the Syrian conflict?

This is re-posted from exactly two years ago. Since then, the Syrian refugee crisis has worsened.

—

The Syrian conflict has become a humanitarian tragedy incomparable to others in recent history. Over 2 million people, 10% of the country, have fled during the ongoing conflict according to the UN.

The Syrian conflict has become a humanitarian tragedy incomparable to others in recent history. Over 2 million people, 10% of the country, have fled during the ongoing conflict according to the UN.

While the proximate drivers of the Syrian conflict are a reaction to an oppressive government, the wave of Arab Spring protests, and other political, social and economic factors, a number of experts have argued that climate change, or at least climate, has served as a “multiplier”.

Links between climate change and the Arab Spring have been suggested for the past couple of years. High wheat prices in 2010-11, driven by droughts in Russia and China, may have contributed to the unrest in Egypt and the overall timing of the Arab Spring protests. In Syria, add on the fact that a severe drought over the past decade has devastated farmers.

From a UN Office of Disaster Risk Reduction report:

Poor and erratic rainfall since October 2007 has caused the worst drought to strike Syria in four decades. Approximately one million people are severely affected and food insecure, particularly in rainfed areas of the northeast – home to Syria’s most

vulnerable, agriculture-dependent families.

Since the 2007/2008 agriculture season, nearly 75 percent of these households suffered total crop failure. Depleted vegetation in pastures and the exhaustion of feed reserves have forced many herders to sell their livestock at between 60 and 70 percent below cost. Syria’s drought break point was the season 07/08 which extended for two more seasons, affecting farming regions in the Middle north, Southwestern and Northeastern of the country, especially the northeastern governorate of Al Hassakeh.

The drought drove internal migration to the cities, depopulating some rural areas:

The drought is causing a high drop-out rate, families left in the area who cannot afford, or do not want, to move are suffering. Some figures estimated the people lifted their villages to be more than one million people. Thousands of Syrian farming families have been forced to move to cities in search of alternative work after two years of drought and failed crops followed a number of unproductive years. The field survey that conducted by ACSAD/MoLA/UNDP in January 2011 showed that most of the houses on villages are left empty and less than 10% are occupied by old people and children, The younger generations left for thousands of kilometers seeking work.

While the Syrian drought, like any individual event, cannot be definitively attributed to climate change, the Middle East and the Mediterranean region is one place where climate models agree that drought is becoming or will become more frequent due to human-induced climate change. From Hoerling et al. (2012):

The amplitude of the externally forced [ED-meaning “human-caused”], area-averaged Mediterranean drying signal (estimated from the ensemble mean of CMIP3 simulations) is roughly one-half the magnitude of the observed drying, indicating that other processes likely also contributed to the observed drying.

Naturally, these connections need to be viewed with caution. Climate change is not solely responsible for the Syrian drought, as natural climate variability and ill-conceived land use and agricultural policy clearly also contributed. And the drought itself is only one of many stressors that led to the crisis in Syria. The fact is we will never be able to precisely calculate the contribution of climate change to a geopolitical event or a humanitarian crisis.

Does the inability to provide a precise answer – the drought is 44% due to climate change – matter?

Inability to attribute events to climate change may make adaptation seem impossible. A solution is to not view adaptation as separate from other development activities. For example, the large aid institutions recommend marrying climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction. In other words, when working on a program or system to reduce future droughts, consider how climate change may alter the likelihood and nature of future disasters.

Right now, any of that would be a luxury in Syria. Dealing with the everyday humanitarian crisis is paramount. Hopefully, in time the crisis will abate enough to work on rebuilding people’s lives and improving the capacity to deal with future droughts.

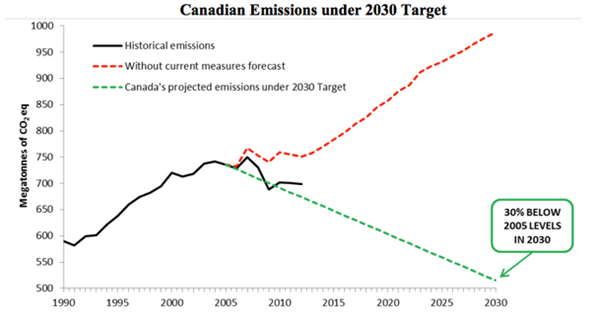

Canada’s moving climate target: the numbers

The Canadian government committed to reducing GHG emissions by 30% below 2005 levels by the year 2030. It was immediately derided by some observers as weak and others as ambitious. It is both: weak in terms of international equity, but ambitious given existing Canadian emissions policy, or lack thereof.

But there’s an even more fundamental problem.

Just what is the actual target?

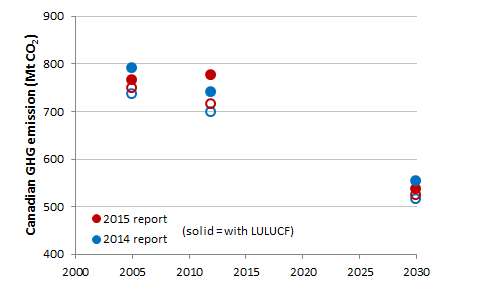

Here’s the chart from Canada’s official submission to the United Nations, technically called an INDC:

The Carbon Brief brought attention to some confusion with the submission. The data in that graph does not include the key category of “land use, land use change and forestry”. Now, it is not that unusual to plot emissions without “LULUCF”, which can fluctuate from year-to-year based on forestry practices, weather, etc. However, the submission states that Canada intends to include LULUCF in calculating future emissions:

Canada intends to account for the land sector using a net-net approach, and to use a “production approach” to account for harvested wood products. Canada will exclude emissions from natural disturbances.

But that’s only the first problem with the data in the Canadian submission.

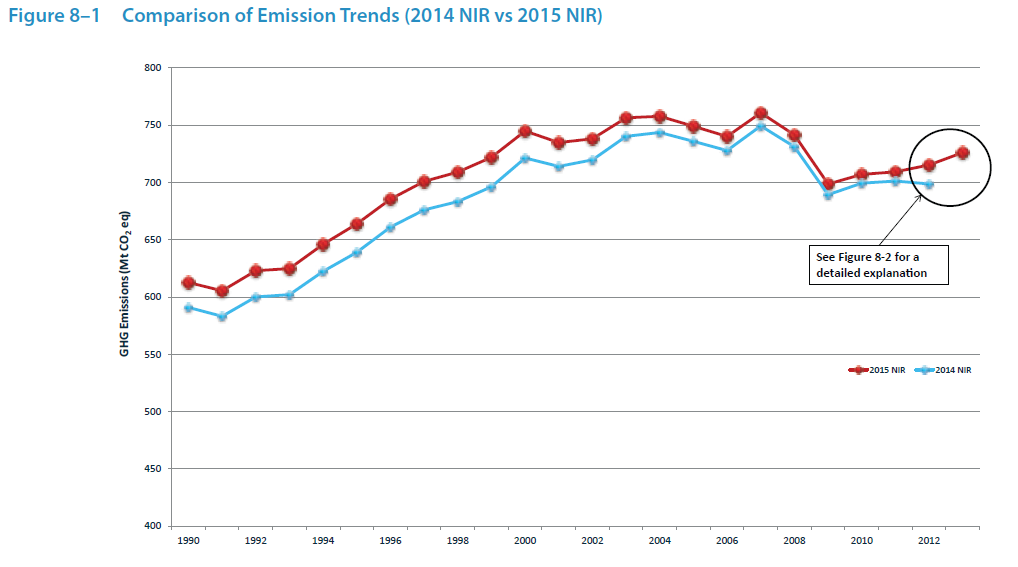

The graph uses historical data from the national emissions inventory completed in 2014, which includes data from 1990 through 2012 (data available from the UN). The latest Canadian inventory report, however, was published in April. Every time one of these reports is compiled, the historical emissions are recalculated based on changes in national and international methods.

Here’s the comparison of old and new, straight from the report (red line is the newest data):

Let’s be clear — the recalculation is not subterfuge. Revisiting past calculations is standard practice and takes legitimate effort.

Let’s be clear — the recalculation is not subterfuge. Revisiting past calculations is standard practice and takes legitimate effort.

The problem is Canada’s own INDC did not use Canada’s own most recent data. Given the recalculation and the confusion about whether LULUCF is included, the 2030 target is a bit fuzzy.

Here’s a comparison of the possible interpretations of 30% below 2005 levels by 2030.

The target could be from 515 to 552 Mt. Semantics? No, the difference is more than half the current emissions from the oil sands. The government itself seems to be confused. Just today, the Environment Minister’s communication person stated the target based on the latest data (749 Mt – 225 Mt = 524 Mt) but excluded LULUCF, which seems incorrect.

The target could be from 515 to 552 Mt. Semantics? No, the difference is more than half the current emissions from the oil sands. The government itself seems to be confused. Just today, the Environment Minister’s communication person stated the target based on the latest data (749 Mt – 225 Mt = 524 Mt) but excluded LULUCF, which seems incorrect.

There seems to be a basic gap in quality and effort between the very professionally done National Inventory Reports and the seemingly haphazard INDC prepared for the United Nations.

Given how challenging it will be for Canada to meet its target, and how little credibility Canada has right now on climate policy, the federal government needs to straighten all this out.