by Meghan Beamish

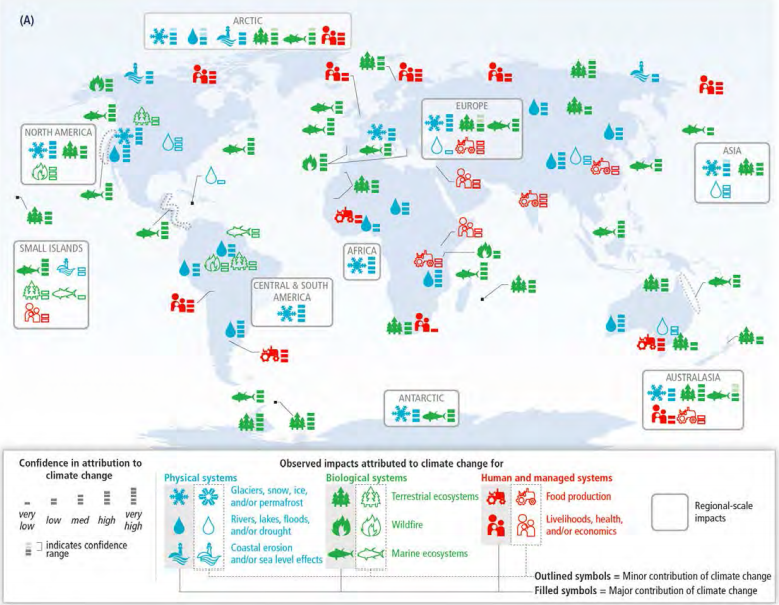

If you’ve seen the new IPCC Working Group II report, you’ve probably seen this pretty graphic:

It shows the observed impacts which published research studies have attributed to climate change in each of seven main regions (and sub regions) of the world. In addition to the observed impacts, the IPCC also published a table of the risks to human and natural systems (Figure SPM.1 if you are following along in the Summary for Policymakers). Risks result from the interaction of climate-related hazards with vulnerability and exposure (of both human and natural systems). Because I live in North America, I honed in on the greatest risks for my continent: wildfire-induced damage, flooding, and heat-related human mortality.

I grew up in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where summer temperatures push 30-40 °C. So that “heat-related human mortality” risk stood out to me. Here are the adaptation issues and prospects that the IPCC outlines for heat-related human mortality:

Residential air conditions (A/C) can effectively reduce risk. However, availability and usage of A/C is highly variable and is subject to complete loss during power failures. Vulnerable populations include athletes and outdoor workers for whom A/C is not available

Community- and household-scale adaptations have the potential to reduce exposure to heat extremes via family support, early heat warming systems, cooling centers, greening, and high-albedo surfaces.

Arguably, arid, hot cities in the Desert Southwest may already be the best adapted to this heat risk. Well, sort of.

Air conditioning is already a way of life in the Southwest. Most homes have some form of air conditioning; when I first moved to Vancouver, it had – embarrassingly – never really occurred to me that they sold – scratch that, made – cars and had apartments without air conditioning. The easy and logical response to those record-high summer days is to crank the A/C. But, while these cool houses in New Mexico reduce the risk of heat-related mortality, relying on current cooling mechanisms is not the best way to adapt to rising temperatures.

Many homes in the Southwest US, where it’s hot and dry, use evaporative cooling systems, what we call swamp coolers. Swamp coolers are fairly inexpensive to operate, and are low-energy users. They will only cool the air within a restricted range, so, when it gets really hot out, they will only reduce the indoor temperature by a certain amount rather than down to the desired temperature set on a thermostat (this also obviously depends on many other factors as well, like insulation).

Swamp coolers don’t work well when it gets humid during our brief “monsoon” season in the late summer. In addition to this, they use a lot of water – anywhere from 3.5-10.5 gallons per hour depending on the valve type. Taking into account that, according to NOAA, the entire state of New Mexico is currently in a moderate to extreme drought, swamp coolers are not ideal.

NOAA Drought Monitor

The other popular cooling mechanism (and the type that is used in most of the rest of the country) is refrigerated air. The upside of refrigerated air units is that that they don’t use any water and they can cool larger spaces to a more precise temperature range. The downside is that they are expensive and use about three times as much energy as swamp coolers. With the majority of New Mexico’s energy still coming from coal power, using refrigerated air as an adaptation is in direct opposition to the mitigation of climate change.

The IPCC suggests that household cooling and cooling centres are potential adaptations to heat-related mortality risks. There is a significant irony in that suggestion. By turning up the A/C on those record-high summer days, we enter a nasty positive-feedback loop. This cooling conundrum isn’t a new issue: check out Stan Cox’s Cooling a Warming Planet: A Global Air Conditioning Surge from Yale Environment 360 back in 2012. Promoting alternative ways to keep houses cool, such as through building practices and alternative cooling mechanisms – with, of course, alternative energy sources – is necessary to reduce the risk of heat-related mortalities without contributing to climate change.