A new sustainability report from the NHL warns that climate change affects “opportunities for hockey players of all ages to learn and play the game outdoors”.

The report on sustainability initiatives may look like a bit of greenwashing from a sports league whose business can involve air-conditioning large stadiums to refrigerator levels in southern U.S. cities during June in order to play a winter activity. Nevertheless, the effect of climate change on outdoor ice, and the culture of Canadians and northern Americans is a real concern.

The “ice season” on lakes and rivers all across the Northern Hemisphere has been shrinking. One of the longest records is from Lake Mendota, in Madison, Wisconsin, where I went to graduate school. The lake may be most famous for this Planet of the Apes stunt, first done by students back in 1979.

The “ice season” on lakes and rivers all across the Northern Hemisphere has been shrinking. One of the longest records is from Lake Mendota, in Madison, Wisconsin, where I went to graduate school. The lake may be most famous for this Planet of the Apes stunt, first done by students back in 1979.

Welcome to the newest sequel, Melting of the Planet of the Apes.

The Mendota ice season averaged 122 days long back when observations began in the 1800s (1885-1875 average). Thanks to climate warming, the ice season is now more than a full month shorter! The average winter over the past twenty years featured only 85 days of ice.

This coarse metric of ice duration only tells part of the story. A lake that once froze in its entirety may now have portions that remain unfrozen all winter. During the record short 2001-2 ice season, enough of Mendota and other neighbouring lakes remained unfrozen that I considered taking my kayak out in mid-February, just for the sheer novelty of paddling in the middle of a Wisconsin winter.

This coarse metric of ice duration only tells part of the story. A lake that once froze in its entirety may now have portions that remain unfrozen all winter. During the record short 2001-2 ice season, enough of Mendota and other neighbouring lakes remained unfrozen that I considered taking my kayak out in mid-February, just for the sheer novelty of paddling in the middle of a Wisconsin winter.

A 2012 study in Environmental Research Letters suggested the shrinking ice trend extends even to artificial outdoor skating rinks. Using rink officials’ rules for deciding when the weather is safe enough to start the ice, scientists calculated that the skating season had shrunk over the past fifty years across Canada.

If the world continues on this greenhouse gas emissions trajectory, learning to skate on an outdoor rink may become a thing of the past, as will a number of key economic activities, like traveling safely by vehicle across the roadless, lake-dotted landscape of northern Canada. In a few more decades, when we’re on to the thirtieth Planet of the Apes sequel, the UW students may have to haul Miss Liberty out on pontoons.

The NHL is smart to be concerned about climate change. A favourable climate is foremost among the reasons that hockey – and watching hockey – is so fundamental to Canadians, and also Minnesotans and Wisconsinites. As the climate changes, culture may too, as we warn in this video. Kids may be less likely to get interested in skating and ice sports… or parents may be less likely to drag their crying kids to the indoor rink to practice. Next thing you know, they may be playing and watching other sports.

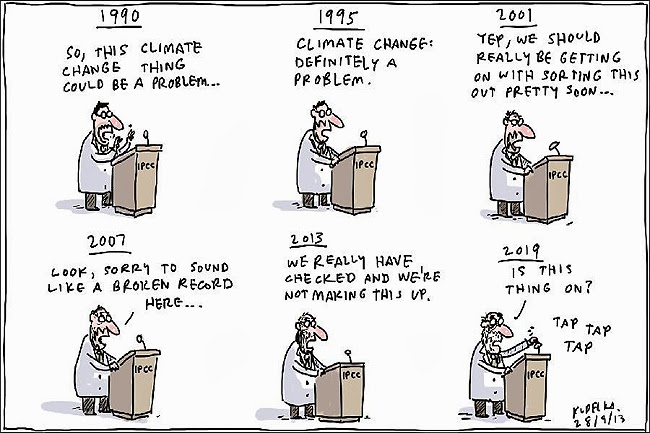

presenting the findings to the public, subjective judgements had to made about which findings warrant mention. Yet this is what someone playing the honest broker would seek to avoid. A partial solution to this dilemma, suggested years ago by Stephen Schneider and discussed in

presenting the findings to the public, subjective judgements had to made about which findings warrant mention. Yet this is what someone playing the honest broker would seek to avoid. A partial solution to this dilemma, suggested years ago by Stephen Schneider and discussed in

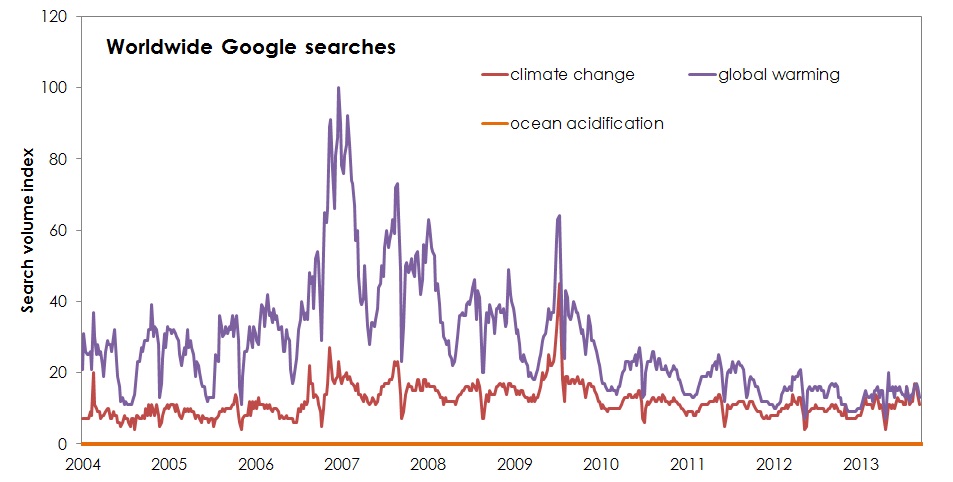

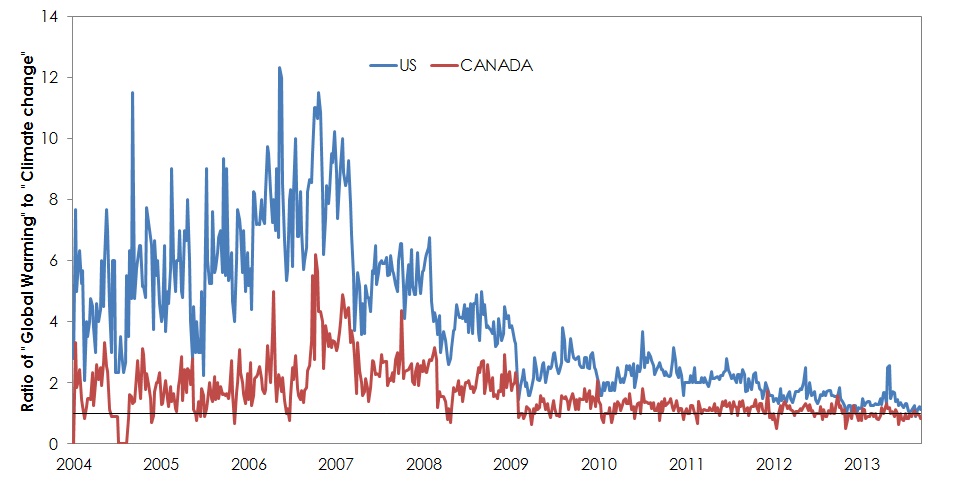

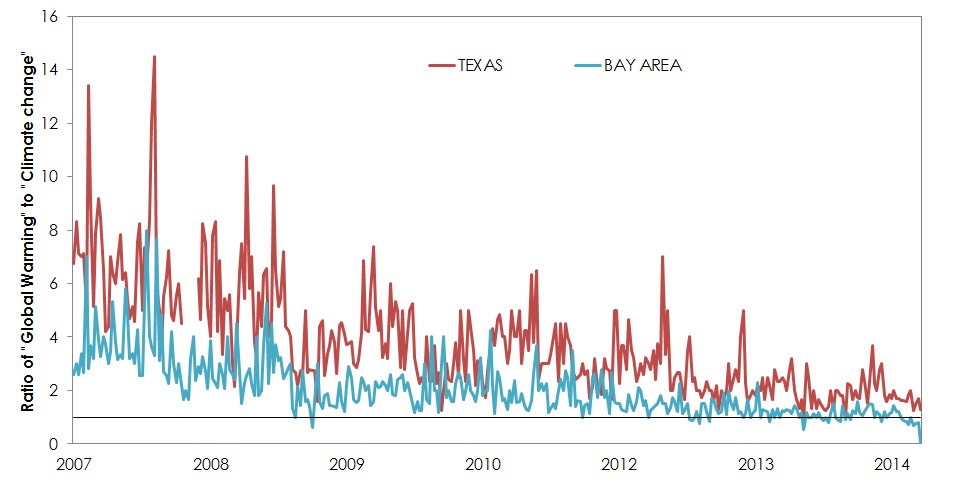

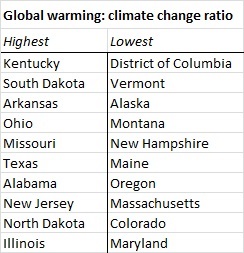

Washington DC is the only “state” where climate change is the preferred term, no doubt related at least in part to its use in government.

Washington DC is the only “state” where climate change is the preferred term, no doubt related at least in part to its use in government.