by Salome Buglass

The bleaching of coral reefs is once again making headlines. Reefs across the tropical Pacific, including the Great Barrier Reef and now reefs in the Indian Ocean, are turning white due to warmer than usual sea temperatures as a result of climate change and the current El Niño. This may be the beginning of a series of mass bleaching events occurring at a global scale, similar to those observed in 1998, 2005, and 2010. Caribbean coral reefs may be the next to experience extensive bleaching, starting at the end of the region’s summer (~August 2016). How coral communities recover from the aftermath of bleaching events is a key question concerning marine scientists and managers as it will determine the survival of coral reefs on an increasingly warming planet.

When sea surface temperatures rise above the normal high for the year, it stresses corals causing them to expel the colorful algae that live inside the corals’ tissue and which provide the corals with their brilliant color and most of their energy needs. Bleached corals are weak and the longer they remain in this state, the more susceptible they become to infectious diseases and vulnerable to partial or complete mortality. Severe bleaching events often lead to significant decline in coral “cover” – the fraction of the reef covered by living corals — and changes in the average colony size. For instance, the average colony size declines as a result of partial mortality or fragmentation. Considering that larger corals tend to have greater reproductive output, a decline in abundance and mean size of coral colonies can greatly slow down the ability of the corals to reproduce, regrow, and thus recover following disturbances such as bleaching.

After witnessing the bleaching among the coral reefs that surround my home island of Tobago back in 2010, I decided to dedicate my Master’s thesis to studying the impact and recovery of these coral communities. With Simon Donner from the University of British Columbia and Jahson Alemu from the Trinidad and Tobago’s Institute of Marine Affairs, I examined changes in coral demographics over time (2010-2013) across three near-shore reef systems with different proximity to urban land. In addition, we tallied the juvenile corals at each reef, as their abundances are indicative of different species’ ability to reproduce sexually and survive. We also assessed sediment deposition and composition at each site using simple PVC pipe traps, as high levels of sedimentation are known to affect the growth stages in a coral’s life cycle. Continue reading

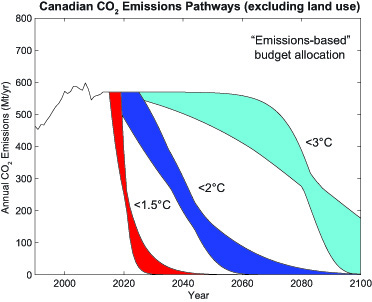

With a generous helping of carbon pie, future emissions pathways for Canada that are consistent with the temperature limits would look like the figure at left. The 1.5°C limit is “at best unrealistic, at worst politically impossible.” The current Canadian target of reducing emissions by 30% below 2005 levels by 2030 could be consistent with the 2°C limit, provided emissions continue to rapidly decline after 2030.

With a generous helping of carbon pie, future emissions pathways for Canada that are consistent with the temperature limits would look like the figure at left. The 1.5°C limit is “at best unrealistic, at worst politically impossible.” The current Canadian target of reducing emissions by 30% below 2005 levels by 2030 could be consistent with the 2°C limit, provided emissions continue to rapidly decline after 2030.