In an ideal world, the racial tensions the Dragon Centre provoked would have been left firmly in the past. Yet racism continues to rear its ugly head in modern Canadian society. In 2017 a woman went on a racist rant towards Chinese employees in the Foody Mart supermarket in Scarborough. Tellingly, despite her screams of “Go back to China!”, no complaints were filed against her (CTV News, 2017). There are many reasons why the employees may not have filed a report, but the fact is that her actions were tolerated, when they should not have been.

In an interview with Global News, Tam notes that the issues described in the City of Scarborough report on race relations remain unfixed today (Tam and Begin, 2017). Planners are sometimes embroiled in issues which are based in racial tensions, and the best thing planners can do is take concrete action. We can see the issue of racism as a by-product of unsuccessful integration on the part of the newcomer Chinese immigrants when they first arrived. As many authors note, integration is a two-way process which involves immigrants learning skills to adapt to Canada’s context but also “recognizes the vital role that established Canadians have in facilitating newcomer immigration, integration, and inclusion” (Biles, Burstein, Frideres, Tolley and Vineberg, 2011, p.2). The City of Scarborough certainly should have defended the newcomer Chinese merchants from the antagonistic attacks on them, but it is important to remember that it was non-Chinese Canadian citizens who are also to blame. Continuing to condone racist behaviour such as the racist sentiment around the Dragon Centre even to this day, seen in the 2017 screaming incident, does not bode well for the future of multiculturalism in Canada.

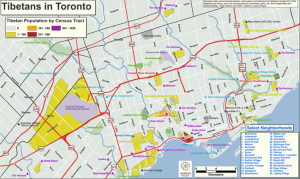

While it remains typical to be reactive rather than proactive in integrating newcomers in ethnic enclaves into the urban fabric, there are a few solutions. Biles et al. call for a campaign that would “encourage inclusion in everyday actions and to promote activities such as volunteering and political participation that build community” (Biles et al., 2011, p. 410). Community-building can, alternatively, come from the ethnic malls themselves. In their study of three Chinese suburban malls in the GTA, Zhuang and Chen found that some of these malls function as community centres by offering dining, social activities, and services (2017, p. 286). Their research found that 25% of the visitors to Market Village and Pacific Mall were non-Chinese, and meeting the needs of the wider community in this way is critical to the success of future suburban ethnic malls (Zhuang and Chen 2017, p. 286).

In the case of Dragon Centre, this would be history repeating itself. Some of the stories that emerged indicated that Dragon Centre was not just a community hub for Chinese people but for the larger Scarborough community. For example, one woman shared the story on Twitter that, although not Chinese, she used to attend school nearby the Dragon Centre and used to skip school to head to the mall (exhibition materials, 2019). Or there’s the story offered by Hallie Church, a woman who grew up in Toronto, who found Dragon Centre to be the perfect place to spend weekend days with her father collecting Sailor Moon trading cards ( see Figure 1, exhibition materials, 2019). Perhaps the priority of Chinese suburban malls, then, must be to continue to adapt to the needs of both the Chinese and non-Chinese community as time goes on.

But is there any point in saving them? In his lecture to our class, Tam argued that we must capture community heritage before it is gone, and that it must include all aspects of community history, even boxy shopping malls (personal communication, October 1 2019). He also cited the City of Toronto’s City-wide Heritage Survey Feasibility Study which asks the public which sites they think should be remembered. Tam thinks proper public consultation will be central to this (personal communication, October 1 2019). The stories we have heard about Dragon Centre are an example of intangible cultural heritage, which, according to UNESCO, includes oral histories passed down to the next generations (“UNESCO – What is Intangible Cultural Heritage?”, 2019). UNESCO notes that “understanding of the intangible cultural heritage of different communities helps with intercultural dialogue, and encourages mutual respect for other ways of life” (“UNESCO – What is Intangible Cultural Heritage?”, 2019). With this in mind, the stories from Dragon Centre are a further way to bridge the gap between Chinese immigrants and non-Chinese residents. They offer a powerful, compelling way to empathize with people from different cultures and find what connects us rather than what divides us. To ensure suburban ethnic malls remain part of Toronto’s identity, they should either be commemorated through stories or strive to meet the current needs of mall users from a variety of genders, races and classes. While it may be too late for Dragon Centre, other ethnic malls can still be saved in our collective memory or in our suburban landscape.

Figures

Figure 1 – the story by Hallie Church at the Dragon Centre Commemoration Celebration event

References

Biles, J. (2011). Integration and inclusion of newcomers and minorities across Canada. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s Univ. Press.

CTV News. (2017). ‘Go back to China’: Outrage over racist rant caught on video. Retrieved from https://www.ctvnews.ca/canada/go-back-to-china-outrage-over-racist-rant-caught-on-video-1.3443983

Exhibition materials. Dragon Centre. October 5 2019. Dragon Centre Commemoration Celebration. Scarborough.

Qadeer, M. (2016). Multicultural Cities. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Tam, H., & Begin, C. (2019). The history behind Scarborough’s Chinatown [TV]. Global News Toronto.

UNESCO – What is Intangible Cultural Heritage?. (2019). Retrieved 3 November 2019, from https://ich.unesco.org/en/what-is-intangible-heritage-00003

Zhuang, Z., & Chen, A. (2017). The role of ethnic retailing in retrofitting suburbia: case studies from Toronto, Canada. Journal Of Urbanism: International Research On Placemaking And Urban Sustainability, 10(3), 275-295. doi: 10.1080/17549175.2016.1254671