The field of media ecology examines the complex interactions between modes of information and communication, the technologies that allow them, and their effects on human feelings, behaviors, and thoughts (Lum, 2000). Including the term “ecology” is not fortuitous, it directly reflects that media create environments that constrain how we communicate, how we behave, how we think. Akin to “biological environments” that shape how living organisms survive and strive, “media environments” carry unique affordances that mold how the human race interact through and within this ecosystem.

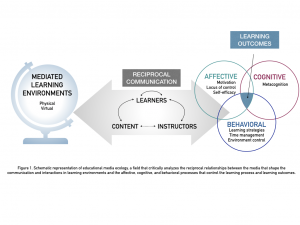

Extending this concept to education, educational media ecology would be the interdisciplinary study and critical exploration of the relationships that exist between learning environments and the culture, communication, cognitive, behavioral and affective processes that take place within this context (Figure 1). Indeed, meaningful learning occurs through a series of two-way interactions between learner-content, learner-peers, and learner-instructor. The nature, quality, and quantity of these interactions are influenced by the affordances of the media through which they occur. Practically, this means that humans interact differently based on the environment in which the communication occurs. While “learning environments” are clearly not restricted to virtual spaces, the recent covid-19-induced shift towards online learning and working provided several examples of this phenomenon within technology-mediated learning environments. For instance, differences in engagement and motivation were obvious between meetings where videos were activated compared to those where only audio was shared. In my own experience, the former sparked more valuable discussions while the latter increased multi-tasking and reduced interest. This is a prime example of educational media ecology focusing on the effects of the media rather than its internal structures (Mumford, as stated in Lum & Strate, 2000).

In return, the quality and quantity of interactions that technology-mediated learning environments promote further affect how humans feel, think and behave (Figure 1). Indeed, the very nature of the technology affects learners’ affective, behavioral and cognitive processes that are central to the learning process. This aligns well with Lum’s (2000) description of media where he argued that diverging symbolic and physical media forms ultimately carry epistemological biases. In other words, the learning environment that media create directly affects how knowledge is accessed, created, and disseminated.

Other crucial features that emerged from this week’s readings is Mumford’s belief in human’s agency and responsibility in creating, shaping and regulating what technology-mediated environments are and are allowed to do (Lum & State, 2000). This highlights the obligation we have, as learners and educators, not only to be critically aware of the inherent biases brought upon by the learning environments we use and create, but also to explicitly assert our control over how media is established and developed.

References

Lum, C. M. K. (2000). Introduction: The intellectual roots of media ecology. New Jersey New Jersey Journal of Communication, 8:1, 1-7, DOI: 1080/15456870009367375

Strate, L., & Lum, C. M. K. (2000). Lewis Mumford and the ecology of technics. New Jersey Journal of Communication, 8:1, 56-78, DOI: 1080/15456870009367379