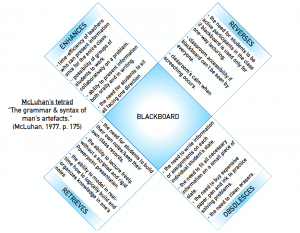

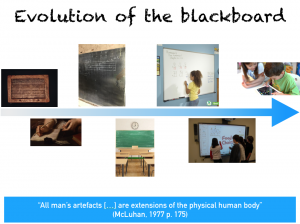

McLuhan (1977) stated that “all man’s artefacts […] are extensions of the physical human body” (p.175). Applied to the blackboard, this statement suggests that, originally, the blackboard allowed teachers and students to display semi-permanently and to share the information that was relevant to them at that specific point in time.

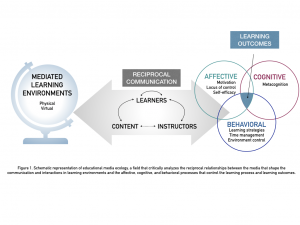

Fast forward 40 years, scholars such as Toohey argue that “people, practices and things [are] continually in relation, under construction and changing together” (2018, p. 29). This new materialism shifts educational researchers and practitioners’ inquiries from “how does this work?” to much more dynamic questions such as “what is this tool becoming?” and “how are we, as humans, and our non-human tools, entangled?” In other words, new materialism studies matter not for what it is (its essence), but for what it does and its capacities to act and affect (its agency) (Monforte, 2018). Furthermore, this framework explores how the entanglement of human and non-human entities co-creates and influences each other’s agencies (Hill, 2017).

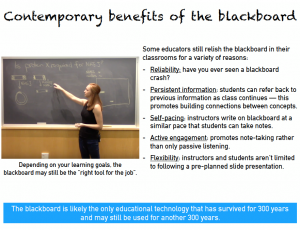

In an educational context, it suggests that the tools we bring into our learning environments are not inert objects. Rather, they have the power and agency to mediate numerous interactions: student-to-student, student-to-teacher, student-to-material, and teacher-to-material relationships can all be altered by the types of objects (e.g. table & chairs, blackboard & interactive whiteboards, tablets & computers, molecular models & representations) present in our learning spaces. For instance, teachers used more open-ended questions and students’ participation quality and quantity increased after interactive whiteboard was installed in primary classrooms (Murcia & Sheffield, 2010). This is an example of how the presence of a technology – and its intra-actions – positioned both learners and teachers as dynamic entities whose vision of the world expanded while living within this material environment.

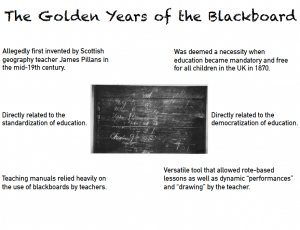

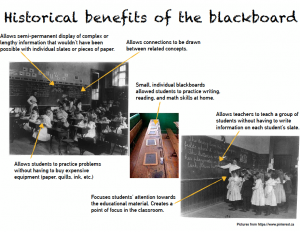

A historical review of the use of the blackboard in our classrooms also nicely highlights how a new materialistic framework expands our understanding of the intra-actions of educational technology onto our societies. James Pillan, a UK geography teacher, is credited for the invention of the blackboard in the early 1800s. From that point onward, the blackboard provided an economical, user-friendly, and well-accepted educational tool (Wylie, 2012). This arguably opened the door to 1) the provision of universal elementary education in the UK in 1870 and 2) to the standardization of English education. Recently, Charteris and colleagues (2017) argued that the promotion of innovative learning environments (ILEs) in New Zealand is brought upon by the pressures exerted by knowledge economy. Similarly, the blackboard carried considerable political power and agency as it facilitated massification of education at a time where the industrial revolution required a large influx of scholarized workers. This nicely illustrates how humans and non-humans are entangled and co-create each other’s agencies, a fundamental pillar of new materialism (Hill, 2017).

References

Charteris, J., Smardon, D., & Nelson, E. (2017). Innovative learning environments and new materialism: A conjunctural analysis of pedagogic spaces. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 49:8, 808-821.

Hill, C. (2017). More-than-reflective practice: Becoming a diffractive practitioner. Teacher Learning and Professional Development, 2(1): 1-17.

McLuhan, M. (197). Laws of the media. ETC: A Review of General Semantics, 34(2): 173-9.

Monforte, J. (2018). What is new in new materialism for a newcomer? Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 10(3): 378-90.

Murcia, K., Sheffield, R. (2010). Talking about science in interactive whiteboard classrooms. Australasian Journal of Education Technology, 26 (4): 417-31.

Toohey, K. (2018). New materialism and language learning. In Toohey, K. (Ed.) Learning English at school: Identity, socio-material relations and classroom practice. (Chapter 2). Multilingual Matters: Bristol.

Wylie, C. D. (2012). Teaching manuals and the blackboard: accessing historical classroom practices. History of Education: Journal of the History of Education Society, 41(2), 257-272.