If you prefer to read through the blog as a narrative unfolding over time, behold:

Since projects rarely end where they start, I post the following to mark (create a record of?) the beginnings of “Archival Interfaces in Virtual Reality.”

An abridged version of the project proposal:

The project will explore potential applications for virtual reality (VR) in the design of archival interfaces, drawing from scholarly literature in the areas of archival access, archives and affect, user experience design and museum studies.

Numerous scholars have commented on barriers to access inherent within the physical spaces of archival institutions. VR may offer a new modality through which to engage non-traditional audiences, and enable interfaces that intuitively communicate archival principles through their design. To date, there have been no published studies on the use of VR in the archival profession.

The objectives for the study are to 1) identify a body of literature to support future studies in the development of archival interfaces in VR; 2) create a working VR prototype interface for a small collection of archival materials; 3) recommend directions for further research.

The project will take the form of an exploratory research design: first, I will conduct a literature search to provide an interdisciplinary theoretical grounding for the study. Using insights from the literature search, I will develop an experimental VR prototype and evaluate it through user-testing with both experienced and inexperienced archival audiences. The project will culminate in a final report detailing the development process, analyzing study findings and sharing lessons learned.

DRM: A Design Research Methodology identifies and attempts to fill a gap in design research by consolidating a set of diverse theories and praxes into a meta-framework that Blessing and Chakrabarti refer to as DRM (design research methodology). The acronym is fitting: the authors appear to propose locking down the inherently heterogeneous field of design research with the aim of making it “more rigorous, effective and efficient and its outcomes academically and practically more worthwhile” (11). Rather than arguing for an expansion and enrichment of academic research by championing the legitimacy of less conventional design methodologies, they instead suggest that design research ought to conform with its norms. Although they situate the concept of the design ‘product’ broadly, noting that it is often conceived as a “mass-produced artefact created by industry” (1), the assumptions underlying their framework are clearly circumscribed by a systems design perspective.

The methodological framework they outline, however, may be useful in drafting a template for the research paper that will accompany the VR prototype, or for articulating the findings of a design research project undertaken in archival studies more generally. It does, at least, offer a series of questions that should be addressed through the design research process, and a systematic way in which to approach them. But, in spite of being cited extensively in the scholarly literature, DRM: A Design Research Methodology is neither integral to the current project nor to a larger discussion of using a design research methodology within archival studies.

Another heavily cited text on the subject of design research is Laurel’s handbook of research methodologies to guide designers in their process. Unlike Blessing and Chakrabarti’s book, the series of essays edited by Laurel is firmly grounded in practice and celebrates heterogeneity within the design field rather than trying to rein it in. Even the presentation of the text itself – purposefully designed, and visually appealing as such – is an endorsement of Laurel’s approach. Design Research: Methods and Perspectives embodies the aesthetic spirit of design in contrast to a strict emphasis on usability that could be attributed to Blessing and Chakrabarti’s book. Of the two, Laurel’s text will likely play a far more significant role in defining the ‘how’ of the design process for the project.[1]

Design Research is divided into four parts: people, form, process and action. For the current stage of the project, the focus will be on the “process” section of the book to help define a design research methodology, although one chapter within “action” – “Social Impact by Design” – also maps out a promising approach. A few essays also specifically take up virtual reality, though it is worth bearing in mind that the book predates the affordable consumer technologies of our own moment by more than a decade. The remainder of the book – discussing qualitative methods (“people”), case studies (“action”) and the nature of artifact creation (“form) – could support later stages of the project.

[1] Not to say that Design Research is above criticism: while Blessing and Chakrabarti’s framework is replete with terms like “Actual Support Description” and “Measurable Success Criteria,” Design Research trades – at times – in its own smarmy bizspeak vocabulary of “fuzzy front end” and “innovation strategy.”

Although Mäkelä’s article is neither recent nor well-known, I include it within the bibliography because it closely aligns with my own notions of how the praxis component of the “Directions for Archival Interfaces in Virtual Reality” project should be positioned. Mäkelä, a ceramic artist and associate professor at Aalto University, provides a succinct and accessible overview to the field of practice-led (design) research, though the brevity of the article requires her to assume a degree of familiarity on the part of the reader with the experience of art or design practice. As a companion to the other two books, it introduces design research in a third disciplinary context – within fine arts – and attests to the pluralistic nature of the field. Given that the current stage of the project is aimed at developing a prototype, Laurel’s and Blessing and Chakrabarti’s texts offer more in the way of concrete steps for embarking on the process – but Mäkelä’s article critically articulates a conceptual stance for the project, one in which the act of making is a process of inquiry and the product created is not only evidence of that process but also an argument (159). Moreover, her brief summary of the theoretical origins of practice-led research hints at the further possibilities presented by incorporating ‘designerly ways of knowing’ into archival theory and practice, which is regrettably outside of the current scope of the project.

In describing the role of artefacts in practice-led research, Mäkelä makes a distinction between “the constructive, solution-focused thinking of the artist or the designer” from the analytic, problem-based thinking associated with verbal and numerical communication (159). While the act of making is understood as a consequence of thinking in conventional research, “invention comes before theory” in practice-led research (159). Mäkelä describes a ‘retrospective look,’ or the act of setting the artefact and the creative process that generated it within a theoretical framework for interpretation (161); in establishing the steps of the design research process for the current project, then, the ‘retrospective look’ may play a key role. At one point, Mäkelä proposes that the artefact is not only an answer to a research question and argumentation on the topic, as established by existing literature on practice-led research, but also “a method of collecting and preserving information and understanding” (158). She does not, unfortunately, elaborate upon her hypothesis but for the recordkeeping profession, it is a provocative idea worth investigating.

Unity may be a popular platform for VR development, but its impressive functionality comes with a not-inconsiderable learning curve. Luckily, a number of great online tutorials exist to build the foundational knowledge necessary to start creating VR apps on your own:

Coursera – Introduction to Game Development, Brian Winn (Michigan State University)

A hands-on, project-based online course (MOOC) geared at teaching learners the fundamentals of Unity; it was my introduction to Unity and I can heartily recommend it. While I have mixed feelings about Coursera as an enterprise, it is not a reflection of the instructors showcasing their work through the platform – Brian Winn has developed an accessible, well-scaffolded and engaging online course.

Lynda.com – Unity Training & Tutorials

Another freemium skill development platform offering a seemingly infinite set of tutorials on Unity, available to many through subscriptions held by their public libraries. The Cert Prep series and/or Unity3D Essential Training are also good place to start as an alternative to the Brian Winn course mentioned above (since many of the same concepts are covered) but there are also a wide range of other tutorials to develop more refined skills (for example, creating architectural models). The website also has numerous tutorials on using Blender, an open source 3D modelling software often used to create digital assets for use in Unity. Needless to say, if you’re working with Blender, you’re well beyond the ‘dabbling in VR’ stage.

Unity, of course, has its own set of free tutorials that are helpful for delving into specific aspects of Unity development, like designing user interface elements and scripting (there is a series on VR, but it relies on assets that are only available to paying users of the software). There are also paid options for courses offered through site, including a VR nanodegree offered in partnership with Udemy.

Not the most exciting of topics, but just to give a general sense of the environment I’m developing in as a point of reference:

VR Development Platform: Unity

Though by no means the only way to create VR apps, Unity is a free (provided that your fledgling VR efforts don’t rake in more than $100,000 in annual revenues) and widely used game development platform with extensive documentation and numerous tutorials available.

VR Build Platform: Google Daydream with Daydream View headset and Samsung S8+ phone running Android Nougat 7.0

There’s a wide variety of headsets, hardware and platforms out there to run VR applications, so I’ll spare you the gruesome details of how I arrived at my particular configuration of stuff. To summarize, the above platform represents a decision to avoid the expense of the higher-end consumer VR systems while still allowing for greater functionality than the controller-less Google Cardboard. I chose the Samsung phone (as a replacement for my archaic, non-VR compatible iPhone 4) because it works with both Daydream and Samsung’s Gear VR (as well as Google Cardboard) in case I want to switch things up in the future.

Computer Doing the Grunt Work: Asus laptop running Windows 10 home

Nuthin’ fancy – I built the prototypes on my 6-month old laptop. I won’t get into the nitty-gritties of its tech specs (Intel i7-7500U processor, 16GB RAM, etc.) – the point is that there’s no need for sophisticated kit to develop in VR.

The first, no doubt, of many little stumbling blocks I will encounter: my enthusiasm for creating archival interfaces was significantly dampened by my foiled first attempts to build and run a demo VR app on my phone (not to mention some generally buggy performance on the Daydream View headset before we came to an undisclosed mutual agreement). Here, I share the solution I found in the hopes of sparing others of the same frustration:

After having set up my development environment according to the instructions provided by Google and Unity, I received an “Unable to List Target Platforms” error message upon trying to send my app to my phone.

Cutting to the chase, the solution can be found here, with heaps of gratitude to the ‘augmentedVR’ user who posted it with a concise explanation of the issue; basically, there are compatibility issues between newer installs of Unity and the Android software development kit (SDK) so that you have to downgrade your version of the SDK tools (or, at least, fool Unity into thinking that you have downgraded them).

Note: you may also need to install Java development kit (JDK) 8 and update the JDK path in the ‘External Tools’ tab under ‘Preferences’ in Unity.

In solidarity.

In the midst of my experimentation with the Unity gaming platform, I’m struck with the idea that I don’t actually know what I am doing.

I refer not to my technical prowess in working with Unity, which admittedly leaves something to be desired, but rather the goal or objective of my design process in a larger sense. Although the exploratory nature of the project suggests a degree of openness in the process, a resistance to closing off avenues, I find myself in the realm of overly abundant possibility. Coming from a visual arts background, I am accustomed to working within constrained circumstances: testing the wiggle room of the rules, finding the pocket universe inside a seemingly bounded space, produces some of the most interesting and challenging work. A more pragmatic expression of the same sentiment is captured by Newell et al., who note that “beginning the design process with a relatively narrow feature list or functionality is advantageous” (238). Point taken.

Am I approaching the design of an archival interface in VR as the creation of a finding aid, a visualization, a virtual space or an encounter? Each paradigm entails a set of assumptions, a conceptual framing. What is the “relatively narrow feature list or functionality” that I am beginning with? Can I determine those parameters without having a comprehensive knowledge of what can be done within Unity? My bull’s run through the china shop continues…

Looking for Answers, winner of the 2017 Theodore Calvin Pease Award, attempts to address the dearth of attention paid to the user experience of navigational features in online finding aids. Walton focuses her study on Princeton University’s finding aid website, noting its broad range of possible user interactions and Web 2.0 features. She recruited 10 undergraduate students to participate in a robust user-testing process that measured the finding aid website’s usability across a series of representative tasks, including questionnaires, think-aloud interviews and a Likert-scale user satisfaction survey. Suggesting that the study results may be generalized to inform usability guidelines within a broader archival context, she makes ten recommendations to improve the user experience in navigating online finding aids. Of particular relevance to a project archival interfaces in virtual reality are the recommendations that concern wayfinding – that is, the ability for users to visually explore collection contents without losing their place and to be aware of their position within the hierarchy of the collection – and that advise keeping the interface uncluttered. An immediate challenge that comes to mind is how to best use the space within the virtual reality environment to convey large quantities of information while still maintaining a minimalist aesthetic.

Walton’s article is useful on multiple levels: if the design of VR archival interface is modeled after a finding aid – and, at the current moment, it is one way that I am conceptualizing the project – her thorough review of existing literature on finding aids provides a convenient point of departure to engage with. But the most astute insights lie in the implications of her findings; for example, the screenshots she provides are a cogent reminder of the logocentric nature of (online) finding aids and the challenges of presenting the same information in virtual reality – how to ‘spatialize’ text by representing it metaphorically. Walton’s observation about the confusion surrounding the “Comments” section of the finding aid cautions against the indiscriminate use of Web 2.0 features – a lesson equally applicable in virtual reality. And while VR offers new avenues for organizing navigational elements – the crux of Walton’s article – within a finding aid, it also entails the risk of exacerbating the user’s sense of being ‘lost’ if the user experience is poorly designed.

In keeping with the conventions of the blog genre: the quintessential apology for not posting more often. Sorry.

So, a bit of catching up is likely in order – specifically with respect to how the project has changed since the carefree days of January where anything seemed possible and time stretched out infinitely ahead of me.

Where things started:

- focus groups, expert interviews, user testing, oh my!

Where they ended up:

- the ethics proposal itself is written and ready to go, but preparing the supporting documentation – from the user testing script to the questionnaire to the follow-up email for the follow-up email – dauntingly threatened to engulf the time earmarked for development of the VR application and so, was ultimately scrapped

- the scrapping of the ethics proposal = no focus groups, no expert interviews & no user testing

I should take a moment here to express my thanks to Jennifer Douglas for reminding me that independent study course students always start out by promising the moon.

The scaled back, more realistic version of the current project then becomes a feasibility experiment to investigate what would be involved if an archives were to undertake a small-scale virtual reality interface design project. The core of what was proposed – identifying a body of literature, creating a series of prototypes and recommending directions for future research – remains the same; it’s just being undertaken without, y’know, any input from the people who I hope would use the application. Failing user interface design 101. But it’s clear that the scope of exploring archival interfaces in VR is far larger than a three-credit academic course, so it will be good to have a point of departure for the next stage of the project…

In their article, Newell et al. take up the difficulty in applying user-centred and participatory design approaches to contexts where user groups contain older adults and people with disabilities. User-centred, participatory and similar design methodologies aim to ensure that the user – rather than the designer – is at the heart of the design process, usually by involving and collaborating with prospective users. The authors note that, while the techniques are useful for conventional design, they are less successful when the population exhibits a much greater variety of user characteristics and required functionality as is often the case with older adults and people with disabilities. Similarly, universal design and “design for all” approaches inevitably prescribe a more normative conceptualization of disability; although a wide range of users may be served by universal design, considering the requirements of marginalized groups may be framed as “an ‘add-on’ extra to an otherwise well-designed product” (236).

The authors propose instead a new methodology: user-sensitive inclusive design, wherein “inclusive” suggests a more realistic and achievable scope than “universal,” and “sensitive” encourages the designer to look beyond physical characteristics and take the whole person in account. Empathy and emotional investment from designers are integral components of user-sensitive inclusive design, particularly in response to approaches that prioritize usability at the expense of aesthetics.[1] To address the representational shortcomings of using invented personas on one hand while avoiding the ethical issues of working with marginalized users on the other, Newell et al. recommend enlisting theatre professionals to act out open-ended scenarios for an audience of designers and, potentially, prospective users. They claim that performance can act as a bridge between design and ethnography, “a tool for making ethnographic insights more visible, exploratory and exploitable within design processes” (241), and conclude with examples how theatrical techniques have been used by the authors and others.

Though “User-Sensitive Inclusive Design” does not speak directly to the concerns of creating archival interfaces in virtual reality, there are nonetheless valuable observations and theoretical insights to take away from it. The authors’ insistence that designers ought to form empathetic relationships with users in order to view them as people rather than as subjects for usability testing speaks to the limited ways in which archival users are typically perceived; that is, in the narrow terms of their information needs. Of particular interest is their regrettably brief discussion of critical design, described as “‘design that asks carefully crafted questions and makes us think’, as opposed to ‘design that solves problems or finds answers'” (238, quoting Dunne) – how then might critical design be incorporated in the context of the current project? The authors’ argument for the importance of aesthetics is also well-taken, given the strictly functional design of most archival finding aids. Lastly, their use of theatrical performance in the requirements gathering stage of design hints at the possibilities within the archival profession to take a more creative and participatory approach to engaging users in the development of interfaces – broadly conceived – to archival materials.

[1] Newell et al. give the illustrative example of walking sticks: where they were once elaborately designed as a fashion accessory, they have since become a blandly utilitarian piece of assistive technology.

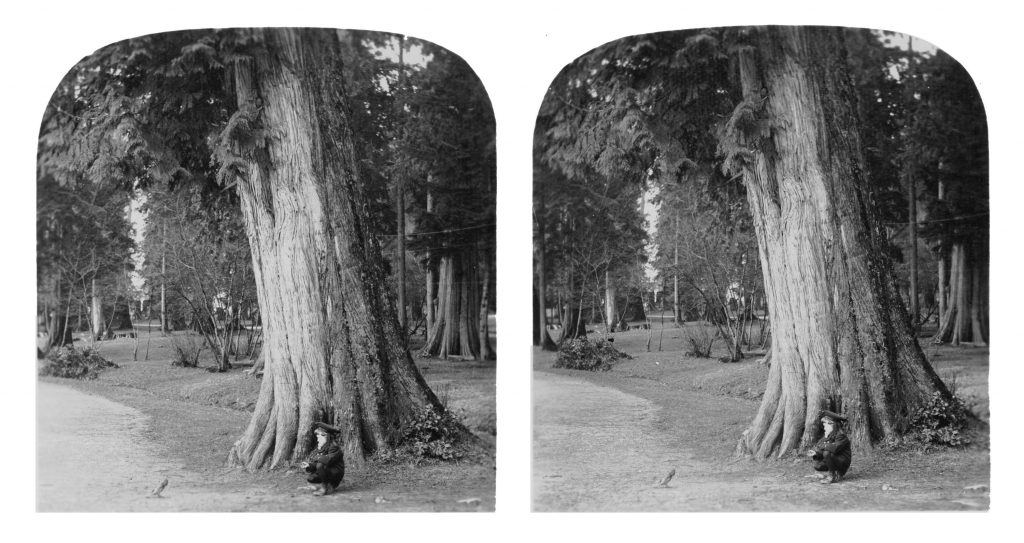

My foray into VR as an interface to archival materials begins by experimenting with archival stereographs, like the one below from the City of Vancouver Archives:

Coaxing the blue jay, Stanley Park – Philip T. Timms (Vancouver Museums and Planetarium Association fonds)

“Archival Interfaces in Virtual Reality” makes its public debut! First at our internal UBC iSchool Research Day, and then in May, I will be presenting the project at the Archives Association of Ontario (AAO) Conference.

For Research Day (March 9), I gave an interactive demonstration of the ‘Archival Interfaces in Virtual Reality’ project (and presented a poster on the ‘Shades of #MAGA‘ project that visualizes the use of the #makeamericagreatagain and shorter #MAGA hashtags on Twitter). It was incredibly helpful to get informal feedback on the stereoscopic interface prototype, and the demonstration ended up tying for first place in the poster competition with Darra Hofman’s delightfully titled “‘A mouth is not always a mouth, but a bit is always a bit, and it matters little what it bridles:’ The relationship between privacy and transparency in digital records.”

One of the things that struck me while watching Research Day attendees try out the prototype was their desire to explore outside of the frame of the prototype – an appreciable fascination with the experience of VR itself. I’d certainly felt it myself upon trying the headset for the first time (I actually teared up a little at Google’s generic welcome screen) but it quickly became forgotten through the repetition of development and testing. The sense of immediacy – and bodily estrangement – has a powerful affective quality that I had wanted to explore with the project but it is also worth considering the threshold of where it becomes captivating to the exclusion of all else (i.e. the archives that it is meant to provide access to).

I also had the opportunity to meet the wonderful Nadia Caidi, our keynote speaker for Research Day, who suggested the possibility of using similar VR tools – given their portability and accessibility – as an entry point into the relationship-building process with communities who are underrepresented within the archival endeavour.

The next stop for the ‘Archival Interfaces in Virtual Reality’ traveling roadshow will be the Archives Association of Ontario conference at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, ON on May 10th, 2018.

Losh’s “Reading Room(s)” surveys the physical and digital spaces of three national libraries – the Library of Congress, the British Library and the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BNF) – and their divergent approaches to the user experience of accessing archival materials in both modalities. Her deconstruction of the libraries’ physical structures emphasizes the degree to which architecture functions to embody political and cultural ideologies, and to control user interactions in the space; that is, “a document archive as a physical space is constituted by prohibitions on reading” (374). She cites the example of the Mitterand Library in the BNF, which physically reinforces hierarchies of privilege by limiting access to one of its two libraries to established scholars only. In particular, she highlights the widely-practiced institutional surveillance of patrons as a condition of using archival materials; it is an important reminder that providing access to archives is not the same as making users feel welcome. By contrast, Losh maintains, the online presence of the libraries affords users anonymity and free entry, and subtly communicates liberal values like open access – though not without contradictions, in terms of the hidden decision-making processes about what to make available.

I include Losh’s article in the bibliography to support a rationale for using virtual reality as an archival interface, but also as a caution that a virtual environment modeled on the physical one may enact some of the same phenomenological barriers. She opens her argument with a pivotal observation: “Just as the physical building in which a national library is housed can serve as a tangible expression of political and cultural philosophy, the architecture of a given digital archive represents and manifests particular ideological features in keeping with the specific national legacy that is preserved and disseminated electronically” (373). Though Losh’s argument focuses specifically on digitization policies, it can conceivably be extended to encompass the design of the diegetic space within a virtual reality archival interface.

What consequences, then, might there be for the design of archival virtual reality environments? Does a skeuomorphic approach risk revivifying the politico-aesthetic ideologies of their physical counterparts? How can residual markers of colonial power and oppression embedded in the virtual architecture of the space evoke unpleasant emotions for different Indigenous researchers, for example? In identifying future directions for the ‘Archival Interfaces in VR,’ a more robust theorization of affective experience in institutional spaces is an urgently needed avenue for further development;[1] we may look to museum studies to bolster the existing archival literature on the topic.

[1] This assumes, of course, that the design of the virtual reality environment attempts to emulate an institutional space. There are innumerable other possibilities; see “Imagining Transformative Spaces: The Personal–Political Sites of Community Archives” by Caswell et al. (just below) for another approach.

Putting the cart before the horse – that is, my skill in Blender is well below the threshold of translating what Caswell et al. describe into practice – “Imagining Transformative Spaces” is nonetheless a central text for thinking differently about what form an archival interface in virtual reality might take. So far, my experiments in Unity have focused on the foreground rather than the background – the actual archival materials themselves, not the space in which they are contained. Ultimately, take out the contents and they all look like this:

The default view for new projects in Unity. I’m posting it because, in my determination, it is not sufficiently original to warrant copyright protection. Unity, if you disagree, let me know and I’ll take it down.

I do not claim that the image above represents some sort of universally shared conceptualization of space, or that the default view in Unity isn’t emerging from its own historical context; it’s just been an underdeveloped facet of the project so far. But the virtual environment of the VR archival interface will be a vital element to consider in later stages of the project (once my skills have caught up?), with respect to the range of affects it is capable of producing.

Caswell et al. take up the physical spaces of community archives, largely overlooked in archival scholarship relative to more formal institutions (which have been characterized alternately as houses, prisons and temples); they use focus groups to examine how the spaces of community archives are imagined by their users. In the archival literature, the metaphor of the home (as semantically distinct from the house) is frequently invoked in relation to community archives – given that numerous community archives are, in fact, housed in private homes, the association is unsurprising. Their findings, however, revealed a more nuanced understanding of community archives by their users and surfaced three major themes: community archives as 1) symbols of representation made manifest [for the marginalized groups they serve], 2) a home-away-from-home or home-but-not-quite-home and 3) a site of potential political activism/a politically generative space (80). The authors also enrich the widely used metaphor of the home by noting its interpretation in terms of “a welcoming space in a hostile climate… a space where their experiences and those of their ancestors are validated… a space where intergenerational dialog—sometimes difficult and unsettling—occurs… [and as an alternative] to the domestic spaces of home, where previously taboo conversations could be started” (82).

For their study, Caswell et al. spoke with community archives users at five different community archives sites; the authors excluded the comments from users of one online-only archives from the article because they did not speak directly to physical spaces. The omission is unfortunate, as it would have provided a unique insight into the affective relationships that remote users experience within online archival spaces. Notwithstanding, what emerges from their account is an aspirational objective for archival interfaces in virtual reality: to foster a sense of representational belonging, what Caswell et al. term the opportunity for marginalized groups to assert that “‘I am here,’ ‘We were here,’ and ‘We belong here'” (89). At the heart of representational belonging, though, is the community itself; difficult to achieve for a technology that is currently imagined and deployed in a highly individualized sense. But the authors acknowledge that the affective dimensions of community archives are not contingent on the physicality of the space, and suggest that digital archival sites may also hold promise for personal and political connection.