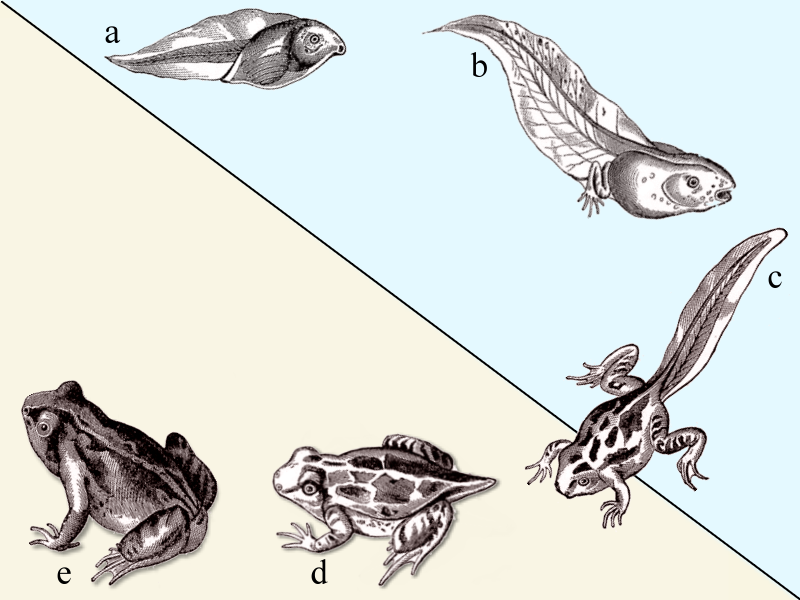

For a tadpole living in a transient pond created by rainfall, the key to its survival may be how fast it can develop into a land-roaming toad before the pond disappears. A study found that tadpoles of the Eastern spadefoot toad (Pelobates syriacus) will speed up their development if they sense the water level around them decreasing.

A lot of Eastern spadefoot toad species live in permanent ponds, so their habitat is stable and provides them adequate time to mature. However, along the Black Sea coast in Dobrudja, Romania, the varied rainfall patterns create ponds that can quickly form and disappear. A toad that hatches in such a temporary pond can’t afford to grow slowly because if the water dries up before this tadpole metamorphoses into a juvenile toad, it risks drying out. Comparing those two types of stable and unstable environments, it’s reasonable to think that toads in quickly disappearing ponds will have a shorter period as a tadpole than the toads in stable ponds.

Then, what if you brought a toad from a stable pond into a quickly disappearing pond? Will they be unsuited to this habitat? No, the toads will actually speed up their growth and mature much earlier than they would have in their other habitat!

The group of Paul Székely, Marian Tudor and Dan Cogălniceanu were able to discover this striking ability by collecting Eastern spadefoot toads from the wild and placing them in tanks filled with water. They randomly placed toads in tanks either with a consistently plenty amount of water, or in tanks where water was scooped out every couple of days to replicate a pond gradually drying out. If the toads can in fact sense the decreasing water level and adjust to it, the toads should reach metamorphosis faster than the ones in a consistent level of water.

Indeed, that is what the researchers observed. When the water in the tank was decreased at a fast rate, the tadpoles started growing legs and maturing significantly earlier than the tadpoles in the consistent level of water – even if the tadpoles of these two groups came from the same pond in the field. Also, when they metamorphosed early, the toads were at a smaller body size. The toads were able to respond to decreasing water levels and end their larval tadpole stage earlier, thus increasing their survival rate if the pond were to disappear.

The researchers also threw in another factor – how about if the water was consistently low, but not decreasing? The onset of metamorphosis for the toads was no different from the toads in the high water level. The water quantity itself didn’t matter – the fact that the water was decreasing was the stimulus for the frogs to start speeding up their development.

There is a cost to accelerating development – the newly metamorphosed juvenile toads generally develop less locomotive ability, have lower tolerance to dehydration or parasites, and have lower reproductive success as an adult. But the immediate benefit of lower mortality – not dying before metamorphosis – is likely greater.

Despite this, the Eastern spadefoot toads are pretty far from receiving a gold medal in their toad development ranking. At least 19 species of toads have the same ability of reducing their larval period depending on their environment, and some of them can reduce their larval periods by more than 60% (Western spadefoot, a North American variant) — if it usually took 42 days to metamorphosis, under the pressure of dwindling water levels, this species would reduce the time to only about 17 days. This is almost 15 times faster than this species (with a 4% reduction in larval period).

…Toads are way cool.

Bonus information:

Another finding from the paper is interesting: the odd thing is, in constant low water, the toads were smaller in size at metamorphosis than the fast decreasing water. Even if they spend the same length of time in their larval period, why would they be gaining mass slower than the other toads? A possible answer is the availability of space. If the toads grew too large, then won’t do well in a crowded environment. Let me know if you think of other reasons!

(Thanks to Dr. Wayne Goodey at UBC for inspiring this post.)