Mussels may be familiar to us on our dinner plates, steamed in butter and white wine sauce. In New York, it has become a city project to study a related type of mussel called the ribbed mussel (Geukensia demissa) in Long Island Sound. These mussels are the focus of a developing technology called “bioextraction” that might help clean up coastal waters.

Ribbed mussels have some fascinating facts – they grow their shells in an annual cycle, so like counting tree rings, we can determine the age of a ribbed mussel by counting the number of ribs on their shells. They can survive in temperatures up to 45°C (a nice hot bath), and a salinity tolerance range of 6ppt to 70ppt means they can live in freshwater-mixed dilute waters or in waters twice as salty as average seawater. With their hardiness and ability to establish quickly, ribbed mussels survived hurricane Irene and Sandy and flourished while oyster species were hit hard and were almost wiped out in the affected regions.

Nitrogen pollution is a growing problem in Long Island Sound as sewage, fertilizers, and other sources deposit nitrogen in those waters. Nitrogen exists naturally in the ocean, but too much of this creates a state called eutrophication – excess nutrients stimulate algal blooms and hypoxia (reduced oxygen) that makes the water less livable to existing organisms.

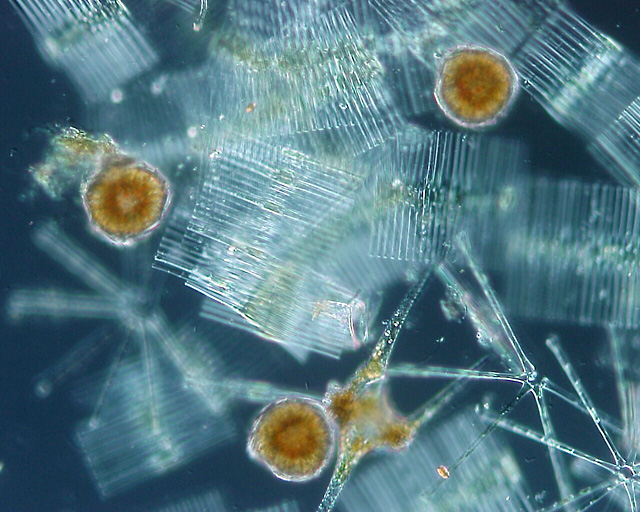

Here is the logic to using mussels. Mussels feed on small algae and plankton that naturally take up nitrogen from the waters. Removing nitrogen or tiny plankton directly from the water is difficult, but the mussels can do the job for us – they effectively collect tiny plankton and nutrients in their bodies, which leaves us to harvest the mussels themselves and as a result remove nitrogen from the waters.

Mussels are like our water filters – pour some seawater through them and they filter out the plankton and algae (containing nitrogen), pumping out clean water. Afterwards, we change out the filter. Even better than filters, mussels can incorporate the excess nitrogen into their shells and meat. This use of shellfish or aquatic plants with similar abilities to remove excess nutrients from the waters is called “bioextraction” (See it explained in a diagram).

Why is this study so special? Bioextraction is the only method known to be able to remove nutrients after they have leaked out to the rivers and oceans. So far, Long Island Sound has tackled various control methods to reduce the nutrient run-off from sewage treatment plants. In 2010, the Hunts Point Wastewater Treatment Plant has achieved an impressive 49% cut in their waste, changing an average of 22,000 pounds a day to 10,800 pounds per day, according to the New York Times. However, they previously did not have a method to deal with the nutrients after it passed the plants.

This bioextraction project, carried out by a commercial shellfish farmer Carter Newell and supported by the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), is one of the first attempts of bioextraction in the Bronx River region along with a project using seaweed bioextraction in the Sound. A previous study in Sweden using blue mussels showed some promising results – mussels have been filtering water and taking up nutrients at a good rate. Although this may be less efficient compared to other filter-feeding organisms like the oyster, mussels can populate the area in dense layers, creating a huge aggregation of mussels. All the mussels combined can filter more nutrients than the oysters that could have lived in the same amount of space. In the coasts of British Columbia, bioextractive technologies using other species including Asian scallop, sea cucumbers, and kelp are being explored (see more: Stephen Cross, “Sustainable Ecological Aquaculture (SEA) Systems: Building a Business Case for Bioextraction”).

You might wonder, where do the mussels go after they are harvested? Ribbed mussels do not appear on our dinner plates – they are known to have an awful taste. However, scientists are exploring the potential use of harvested ribbed mussels as fish feed, chicken feed, or fertilizer. Fertilizer is responsible for a large part of the excess nitrogen in coastal waters, so using mussels in the farms effectively returns the nutrients to its source.

You can follow their progress as scientists closely monitor the impact of introducing ribbed mussels into the new environment and the native populations of mussels, algae, and plankton to evaluate whether this is an environmentally-responsible and effective solution against eutrophication.

Additional note on mussel species –

Mussels are also known as being invasive species in North America. For those of you who have learned about keystone species, you know that mussel populations can explode without a natural predator such as a Pisaster sea star. The invasive mussels in BC are actually a different species – commonly quagga mussels (Dreissena bugensis) and zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorpha).

Hello there, You’ve done a great job. I抣l definitely digg it and personally recommend to my friends. I am confident they will be benefited from this web site.