Late last year I attended a meeting of the Irrigation Association of British Columbia here in Kelowna. The meeting included many professionals from the irrigation industry, as well as a mixture of local government representatives and people from other sectors impacted by the irrigation.

The highlight of the event was their main speaker, Doug Bennet, from the Southern Nevada Water Authority (click to see the program). Doug did a fantastic job of describing some of the challenges that his group faces, and provided some thoughts on how the lessons learned in Nevada may have relevance for the Okanagan.

Like Nevada, here in the Okanagan most of the water consumed by residential water users is used on lawns. In fact, as Neil Klassen with Kelowna’s Watersmart program pointed out, most of the water used inside the home is simply recycled through the lake. Most of what we put on our lawns ends up in the atmosphere, either passing through plants or simply evaporating. So, for the city of Kelowna, saving water is pretty much all about reducing outdoor water use. The most effective way to do that is to convert our landscaping to something that needs little or no water.

If getting rid of our water demanding lawns is so good, why don’t we do it? In Kelowna, we pay for our water (click to see the rates). Ripping out a lawn and replacing it with water conserving landscaping will reduce our water use. But the complete economic picture also includes the cost of replacing the lawn, not just the savings on reduced water use.

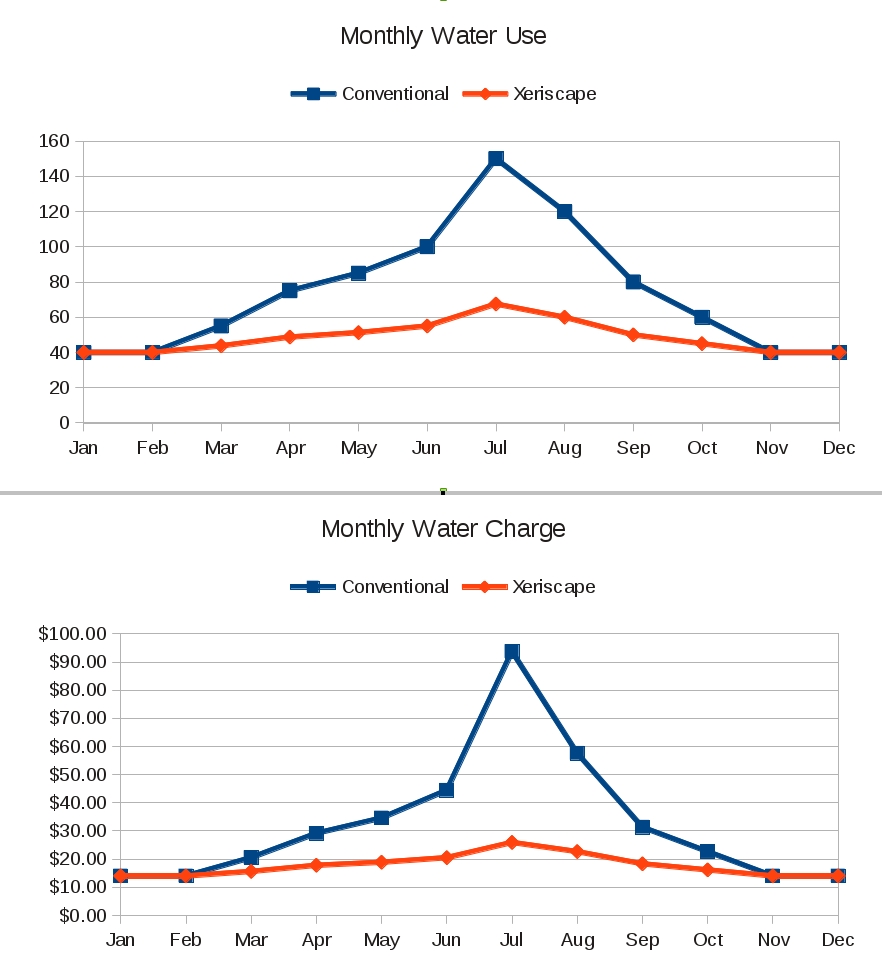

To calculate the benefits, we need to estimate the water use, how much water will be saved, and what the impact will be on the total water bill. This isn’t quite as easy as calculating the water saved and multiplying it by the water price because the price of water goes up the more water one uses. In the summer, when water use is highest, the savings is also the highest. The top chart in the figure below shows the water savings and financial savings for a household that normally uses 40 cubic meters per day in the winter and uses almost four times as much in July. About half of this households water use is outdoor use, everything above the basic 40 cubic meters per day. If this household reduces its outdoor water use by 75%, possible with Xeriscaping, then its water use would fall to the lower line in the graph.

Water Use and Water Charge for a hypothetical household that uses 885 cubic meters of water per year, almost half of which is used outdoors.

The lower half of the figure shows the monthly water charge that the household would face. The rate structure used by the city means that the financial savings, as a percentage of the water bill, is bigger than the water savings. This is meant to create an incentive to save water on those things that push household use up beyond basic needs, but to leave basic needs affordable. For this hypothetical household, the savings is about $180 per year. The savings won’t take the family to Hawaii in February, but it will give them a nice night out.

Are there any other benefits? People who promote xeriscaping talk about the time savings. Maybe two hours of weeding and trimming per month instead of eight hours of mowing the lawn. If it would cost you $20 per week to pay the neighbour’s teen to mow the lawn, then this is another $60 in savings for each month, and maybe $360 or so per year if that lawn would have to be mowed for six months. A bit ironic that the time savings is worth twice the water savings, even though we are promoting xeriscaping because of the water savings. Of course, if you enjoy mowing the lawn – maybe it is an excuse to get outside, and maybe the rhythmic sound of the motor is somehow soothing – then this is not really a savings.

So we might save as much as $480 per year by converting our yard. Now what about the cost? A study by Kyra Dziedzic at the University of Lethbridge did a bit of a cost-benefit analysis of xeriscaping (click here). Kyra found that the cost of xeriscaping a yard was around $8 per square foot. Kyra estimated that for water rates in Lethbridge, xeriscaping would turn a profit for the home owner in something over 500 years! If my hypothetical home has a 66 feet by 120 feet yard, half of which is lawn, then the conversion cost would be $31,680. If we count the time savings, then it would take 66 years to pay this back. If we don’t count it, then it would take 176 years.

These numbers don’t make xeriscaping an existing yard a very smart financial option. Why then would anyone do it? How can we get people to change? Are there any policy tools we can use to encourage more xeriscaping?

I’ll continue some thoughts on this issue in a future post. In the mean time, I’d welcome any thoughts you may have. You may change my own ideas before I post again!

Follow

Follow

I am all for increasing he amount of xeriscaped back yards in the Okanagan; but there are a couple of important differences between Southern Nevada and here that need to be considered when making any comparisons: average temperature and average rainfall. Kelowna gets at least ten times as much precipitation as Las Vegas and the summer temperatures are considerably lower. In Southern Nevada hardly anything grows without irrigation. In Kelowna in a xerscaped yard a lot of unwanted plants will come up, even when weeds are suppressed with woven landscape cloth. This means either increased use of herbicides or increased hand labour pulling weeds. Short of paving the backyard, which is not desirable for reasons of storm water management, unwanted plants will be an issue.

Another question I would like to see discussed is whether green lawns reduce the need for air conditioning?

Interesting post. I have one comment in relation to the cost benefit analysis. The analyses appear to be based on current water rates. However in BC at least, many water suppliers do not set water rates at a level that truly reflects the cost of the water supplied. In particular costs to improve or even adequately maintain infrastructure are not included in setting rates paid by consumers. Would the time to recover the cost of xeriscaping be significantly reduced if the true cost of water was used in the analysis?

Andrew, you have hit one of the main issues, the disconnect between what residents pay in their water bill and what the benefits to the community as a whole are for conserving water.

It’s doubtful that residents of Kelowna would embrace 100% Xeriscaping in their front and back yards, and it’s not likely that our water conservation program would promote that. Turf grass does have its benefits, including reduced soil erosion and reduced heat buildup. Plus, it is ideal for children to play on. However, there are many instances where front yards, side yards, and areas that are seldom used could be Xeriscaped. Perhaps up to 75 per cent of a landscaped area could be Xeriscape, leaving 25 percent turf for play areas, etc.

I believe there are less expensive ways to convert an existing landscape to xeriscape than $8/sq ft. I did mine for $2.50/sq ft (not including labor), which included a small patio and retaining wall. And I think the maintenance cost savings in your analysis could be fleshed out, for example, I know instances where maintenance can go from 8 hrs monthly to 1 hour monthly, at $30/hr (which is not unreasonable in my opinion), this is $210 savings a month.

I’m not sure why Kelowna residents wouldn’t embrace 100% xeriscaping, given that xeriscapes include turf! We need awareness of what defines a xeriscape – it is simply a method of gardening that uses less water, no chemicals (*if done properly*), and needs less maintenance (*if done properly*). I still have 300 sq ft of gorgeous turf in my home xeriscape.

As usual, analyses like these seem jarringly over-simplified. For example, part of my own reason for xeriscaping is to increase my property value in a gentrifying neighborhood where all the new nice houses have nicely xeriscaped yards. There are also reasons like wanting to have a nice yard even during droughts when I can’t water because of restrictions, or wanting to have my yard fit into my sense of what’s appropriate in this semi-arid environment. The latter is somewhat a matter of aesthetics (a large green lawn clashes garishly, in my mind, with the golden browns and grays of the surrounding hillside), but also my desire to leave resources for others (do all economics models have to assume selfishness?). I know that economic models have a place in this, but it is difficult to have robust generalizations.

In response to some of the other comments, I have no fear of xeriscapes – weeds, heat islands, etc…, because I lived for many years with a great xeriscape in California, where the piles of natural wood mulch on the ground and large healthy plants made things feel cool and luxurious.

Here’s my own xeriscaping blog post: http://www.obwb.ca/blog/2012/05/learning-from-the-landscape-cultivating-a-sense-of-place-in-the-okanagan/

Thanks Anna, and everyone else, for participating in this discussion. There have been many good points here, things which are not captured when one looks only at the impact on the home owner’s wallet. Please stay tuned, as I hope to present some more xeriscaping economics in a couple of weeks.