Bill 18, the new Water Sustainability Act, was presented for first reading in the BC legislature on Tuesday the 11th of March. The legislation appears to embody most of the ideas set out in the legislative framework circulated last fall.

In general, integrating groundwater into the surface water licencing system, providing a clear space for the environment, speaking to First Nations water rights, etc. are good directions. I think that the government deserves some credit for its efforts to engage British Columbians and develop an act that reflects a balance of what it heard. The government also clearly has some priorities that are reflected in the proposal. Reading between the lines, these priorities seem to be that the new act will not be too disruptive to the BC economy, not seriously impact areas of strong current and potential future economic growth, and impose the minimum possible additional costs on current and new water users.

Reading the act, it seems to have very few teeth. Much is left to the discretion of the minister or a decision maker. At one level, this is disturbing. Implementing this act may change very little about how water is managed in BC. On the other hand, this flexibility does mean that the act does not tie our hands too much. Either way, the critical piece will be the regulations that are written to implement the act. Will those regulations provide clear processes for activities like determining minimum flow requirements, initiating a water sustainability plan, etc.? As always, the devil is in the details, and when it comes to implementing the act, those details are still missing.

My internet browser generated a 162 page document when I printed it (to a PDF file, no trees harmed). It is a long, tedious read which is difficult to give full attention to. I am not done with it yet. What follows are things that captured my attention. It is not a comprehensive review, and as I am not a lawyer, these are my opinions only. I hope that they contribute to the discussion of this potentially important piece of legislation. I will keep adding to this document as I find time.

14( 11) For certainty, a use approval may be issued authorizing the diversion or use of unrecorded dedicated agricultural water for any water use purpose on any land.

There was a lot of discussion about an agricultural water reserve in the early days of the Water Act Modernization (WAM) process. Does this clause mean that any agricultural water reserve is a reserve in name only? It sounds like water reserved for agriculture can be used for anything else. There are no conditions here, such as the use approval being temporary, being allowed only so long as there is no agricultural need for the water. Does this clause mean that should a water reserve be implemented, the government can just pull water out of that reserve as it sees fit?

Early on in the discussions about a water reserve I was worried that should the proposal not be developed with a mechanism for moving water into and out of the reserve, the government would retain for itself the authority to do that.

23 (2) On the direction in writing of the comptroller or a water manager, a licensee who holds a licence to which this section applies must submit to a review of the terms and conditions of the licence,

This section does make all water licences (barring explicit exceptions for power, industrial development, or a water use plan), whether issued in the future or issued in the past, subject to a potential review after thirty years. This provides some clarity that will make it easier to change licences that are shown to be inappropriate, such as for over-allocated water sources. Without this statement, I suspect that each effort to amend a water licence would be met with stiff, possibly by lawsuit, resistance. With this provision, the battle will not be about whether the government has the authority to review and change a licence, but rather whether it has applied the right criterion for making such a review.

The authority to demand the review and what will be part of the review rests with the comptroller or a water manager. I suspect that the regulations written to implement the act will provide more detail about how and what to include in the review. Will the decision maker be responding only to complaints? Will there be an automatic trigger for a review if stream flow has been low? If there has been a change in land use? A change in economic activities? Will there be a process whereby a public notice is given that particular licences are now past the thirty year date, so that the public can get involved and push for a review?

30 (1) A person who diverts water must make beneficial use of the water diverted.

The beneficial use clause remains. This is also known as the ‘use it or loose it’ clause. An addition here is the ability of the decision maker to require a water conservation audit. This is a nod to the fact that a water user may not be using their water allocation as efficiently as possible. Whether a water conservation audit is done is again left to the decision maker. How will the regulations influence this? Will there be situations where a water use audit is required? Perhaps if a source is closed to further diversions or over allocated, an audit should be mandatory.

Who will do the audit and how much will it cost? If the government is requiring water users to be efficient, and will use audits to establish whether or not a user is being efficient, will it also ensure that water users have access to the information they need to achieve the required level of efficiency? Will there be financial assistance to help water users achieve efficiency?

The approach to efficiency represented here is something of a negative incentive. Water users have a duty to use the water they are allocated as efficiently as possible, for fear that their allocation will be reduced if they don’t do so. There is no real benefit to being efficient. Assuming there are no benefits to efficiency beyond water conservation, the best thing for a water user to do is to wait until there is an audit, and then implement the technologies required by the audit. To do otherwise would be to absorb costs that do nothing other than save water, and may in fact simply enable other water users to continue to be inefficient. I.e. if I reduce my water use, leaving more water in the stream I draw from, then there may be less risk of the stream drying up, and less to trigger a review and water audit of other users on the same source.

39 (1) If the Lieutenant Governor in Council considers it advisable

(a), (b), (c), (d), …

the Lieutenant Governor in Council may reserve all or part of the water that is in the stream or the aquifer, and that is unrecorded and unreserved and is not dedicated agricultural water, from being diverted or used under this Act …

Sounds like agriculture is getting special treatment. Dedicated agricultural water cannot be taken to be part of a reserve for other purposes, such as retaining water in the stream. Does this mean that agriculture does not have to give up water for environmental needs?

However, there are a couple of qualifications too:

39 (8) Despite subsection (1), a licence may be issued authorizing for domestic purpose or a land improvement purpose the diversion or use of water to which a reservation established under subsection (1) applies.

39 (9) Despite subsection (1), a use approval may be issued authorizing, for any water use purpose, the diversion and use of water to which a reservation established under subsection (1) applies.

So, a reserve is not really a reserve, as use approvals may be issued for any purpose. As noted earlier for 14 (11), it seems that a water reserve is a reserve in name only. It sounds like can be overridden. It makes sense to have a means of adjusting a reserve, as situations do change. Perhaps the details of an adjustment process will be part of the enabling regulations. Absent some clear process, it sounds like a water reserve is not a particularly strong tool.

40 (3) Despite anything to the contrary in this Act, a water reservation established under subsection (1) for purposes authorized by the final agreement

(a) is deemed to have been established on the date specified in the final agreement as the reference date for the priority of the water reservation, and

(b) has priority for those purposes over water licences issued after that date in relation to the same stream, except water licences given priority by that final agreement.

Discussions with First Nations were a significant part of the WAM process. This section sets out that if treaty negotiations lead to an agreement about water, that agreement will be treated like a water reserve. That reserve will not be subject to 39 (8) and 39 (9), which I described above. I.e., if a treaty is negotiated, the resulting water reserve cannot be overridden by the water manager.

Section 40 (3) though seems to read that the priority date of water in a First Nations water reserve is the date of conclusion of the treaty negotiations. My naive understanding of the treaty process is that First Nations are just that, Nations, and that they have reserved for themselves all rights that were not explicitly signed over by treaty. Thus, First Nations in BC have never signed treaties providing the provincial government to set up a water rights system and assign priorities to water use. If this section means that a First Nations water reserve will be junior to existing water rights in the area of concern, I doubt it will get very far.

I’m not a lawyer and not familiar with First Nations water litigation in Canada. In the US, the precedent case is the Winters v. United States case decided in 1908. It held that when treaties were signed, there was an implicit agreement that there were water rights sufficient to make economic use of the reservation lands agreed in the treaty. Will a similar interpretation be made here? The Winter’s Doctrine refers to water rights that are implicitly created to accompany treaty lands. If First Nations in BC do not have treaties, does that mean the courts will agree with the wording in the proposed act? Namely, that any First Nations water rights will only have priority consistent with signed treaties? Does the Aboriginal Rights and Title provisions in the Canadian constitution imply water rights that have a priority ahead of all others. More work for the courts I suspect.

Water objectives

43 (1) For the purposes of sustaining water quantity, water quality and aquatic ecosystems in and for British Columbia, the Lieutenant Governor in Council may make regulations

(a) establishing water objectives for a watershed, stream, aquifer or other specified area or environmental feature or matter

This section seems to provide more clarity to the water managers when making decisions around water, if water objectives have been established. The decision makers had considerable discretion under the previous act, and I suspect could have made many of the same decisions as are enabled under this new wording. However, issuing a water objective will provide direction and bring some consistency to decisions.

65 (1) The minister, on request or on the minister’s own initiative, by order, may designate an area for the purpose of the development of a water sustainability plan

There are a number of clauses that refer to water sustainability plans. Water management plans existed under the previous act. The new wording leaves the authority for starting the planning process with the minister. Interested parties in a potential planning area can request that a planning process be initiated, but unless regulations specify otherwise, the minister is not obligated to act on such a request.

The minister is also responsible for setting the area, the issues to be included, and the issues to be excluded, from a planning process. Those in the planning area cannot decide for themselves what the plan will deal with. They can only try to influence what the minister specifies. Of course, it is possible that regulations will set out a process for consultation that leads to the development of a plan.

68 (1) The terms of reference for a proposed water sustainability plan must include the following:

(a) …

(e) an estimate of the financial, human and other resources

required for the plan development process and a description of the

funding commitments and committed sources of other resources

identified in the estimate;

(f) …

Developing a plan will be expensive. Thus, it makes sense to have an estimate of what the cost will be and how it will be paid for. Will the government provide the financial support necessary? Based on recent experience, it would not be surprising that the government response would be ‘we don’t have the resources’. This will mean that people in a watershed will likely have to come up with the resources for the planning process on their own.

At one level, this is not necessarily a bad thing. Most of the benefits of a plan will flow to those in the watershed area affected by the plan. It therefore makes sense that those in the watershed also pay for the cost of developing the plan. However, in most situations where a plan would be valuable, there will be current water users who will not want a plan. Getting people to voluntarily contribute to the cost of developing a plan will be challenging. Getting everyone involved will also be difficult if some people feel they will be better off staying out of the process and sabotaging the process. Voluntary processes work best when they are backed up by a big stick.

For raising revenues, one option would be a surcharge on water rentals. For example, if a planning area is determined and a projected cost is estimated, the water rental rates on all water licences in the planning area can be increased to raise enough money to pay for the planning process. This would make every water user contribute to the cost of developing the plan. Initiating the planning process could also depend on a referendum or some other approach that can reasonably assess if the majority of people in a watershed or relevant area want to develop a water sustainability plan.

74 (2) If a proposed plan submitted to the minister under subsection (1) recommends a significant change in respect of a licence or a drilling authorization and the holder of the licence or drilling authorization has consented to the change, the proposed plan must be accompanied by

(a) …

(b) a detailed proposal assigning to each person or other entity who would benefit from implementation of the recommendation some or all of the responsibility for compensating the licensee or drilling authorization holder, consented to in writing by each such person.

74 (3) If a proposed plan submitted to the minister under subsection (1) recommends a significant change in respect of a licence or a drilling authorization and the holder of the licence or drilling authorization has not consented to the change, the proposed plan must be accompanied by

(a) a list of the affected licences and drilling authorizations,

(b) a statement of the public benefit from the significant change, and

(c) a statement of any available source of funding to pay compensation or for compensatory measures for the involuntary significant changes.

One of the key stumbling blocks for any planning process would be bringing in those who felt they would be worse off with a plan. Existing water users who would have to reduce their use and make room for other users or the environment are of course the most likely to be opposed. These clauses put compensation for those changes front and center.

Recognizing that some people who have been using water in a way that they are legally entitled to may be made worse off by a plan is critical. Too often the conversations seem to assert that those using water have a moral responsibility to reduce their use for the good of the environment, with little recognition that to do so may adversely affect the water user. A classic Okanagan example would be hay or fish. A rancher’s living may depend on growing hay, while the fish depend on water in the stream. Historical ignorance may have lead us to over allocate water from a particular stream, and as a result the fish in that stream may be under threat. However, the rancher using the water is legally entitled to do so, and uses that water to make a living. Requiring her to use less, thereby having to purchase more hay, and seeing her already thin profit shrink even more is the reality of putting more water in the stream. If she knows that she will be fairly compensated for her loss, then she is far more likely to participate in the planning process. Absent this security, she is likely to stonewall or even try to oppose the process.

The challenge of course is how to determine fair compensation. The WAM process came down quite clearly against any sort of tradable water rights. Absent a water market, determining the value of the water to the user who is being asked to give it up will require some form of accounting exercise. The value of water will depend on what it is being used for, where it is being used, when it is no longer available, and how much will no longer be available. It is highly context specific. Where a water sustainability plan is being developed, I expect that the government will strongly encourage the involved parties to arrive at a negotiated agreement, as by 74(2). A freely arrived at agreement is also more likely to be followed by the participants.

79 (1) For the purposes of a water sustainability plan, the Lieutenant Governor in Council, by regulation applicable in relation to all or part of the plan area, may direct the comptroller or a water manager to

(a) amend the terms and conditions of licences identified in the regulation, regardless of the precedence of the rights under those licences, to reduce, in accordance with the regulation, the maximum quantity of water that may be diverted under the licences from a specified stream or aquifer, or

(b) cancel licences identified in the regulation.

Water sustainability plans are potentially a very powerful tool. Under the terms of a plan, water licences can be amended or cancelled. Other sections of the act also assert that a water sustainability plan may put limits on land use.

82 (1) For the purposes of a water sustainability plan, the Lieutenant Governor in Council, by regulation applicable to all or part of the plan area, may dedicate, for qualifying agricultural use on qualifying agricultural land in the plan area or part, a specified quantity of water, in a stream or aquifer, that is

(a) both unrecorded and unreserved, or

(b) held under a licence issued for a qualifying agricultural use on qualifying agricultural land in the plan area.

82 (3) A regulation amending or repealing a regulation under subsection (1) must specify the date on which the amendment or repeal is to come into force, which date must be at least 30 days after the amending or repealing regulation is published in the Gazette.

Section 82 (1) describes the agricultural water reserve. Any agricultural water reserve must be part of a water sustainability plan. To me, this makes sense. We cannot reserve water for agriculture without taking into account the other water uses in a watershed. Making it part of a water sustainability plan means that the agricultural community must engage with the other communities and arrive at an assignment to reserve for agriculture that everyone can agree with. An agricultural water reserve will therefore not become a way for agriculture to secure water for itself, irregardless of the impact on others.

Section 82 (3), as some other clauses mentioned above, sets out the limits of an agricultural water reserve. A reserve can be overturned. This is of course necessary, as situations may change, making an agricultural water reserve a burden. This clause does not set out how decisions to amend or repeal an agricultural water reserve will be made. Will the government prepare a process for this, or will it be left to the discretion of a minister or a decision maker? Will we have an “Agricultural Water Commission” that can approve or deny changes, based on net benefit to agriculture or some other criteria. The final regulations will be very important.

84 (3) A plan regulation does not apply to licences applied against a water reservation referred to in section 40 [treaty first nation water reservations] or 41 [Nisga’a water reservation].

Good.

85 (1) The minister, by order, may direct that a water sustainability plan be reviewed to determine whether the plan should be amended or cancelled.

Necessary, but how? Will this be left to the minister’s discretion, or will there be a process for review? It is interesting that section 73, which specifies the content of a proposed plan, does not include a review process. This is likely one of the greatest weaknesses of the water sustainability planning process.

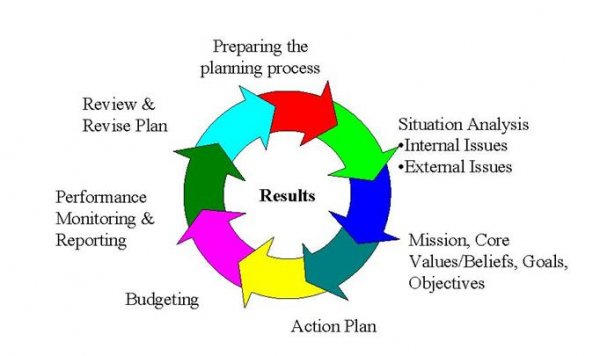

There are a wide variety of ways to describe the strategic planning process. The one unifying feature is that it is described as a cycle. Plans are not made and then followed, but rather implemented, then reviewed, then revised, then implemented, then reviewed, … Planning is ongoing, and the review and revise step is critical. The sections of the act describing water sustainability plans does enable the plans to be very powerful. However, the plans continue to be something that is imposed on an area from above. At best, there will be continual engagement between the ministry and the people in the plan area, and the plan itself written to be adaptive. However, there is no guarantee in the legislation that this will be the case. Given the scarce resources of government, a water sustainability plan may be seen as a way to solve a problem, and then move on. A plan would only be revised when it is clearly not doing the job it was meant to. It would be much better for the plan to be built so that those affected by the plan are engaged in an ongoing way in assessing its effectiveness and making adjustments where the effectiveness is shown to be lacking.

There are a wide variety of ways to describe the strategic planning process. The one unifying feature is that it is described as a cycle. Plans are not made and then followed, but rather implemented, then reviewed, then revised, then implemented, then reviewed, … Planning is ongoing, and the review and revise step is critical. The sections of the act describing water sustainability plans does enable the plans to be very powerful. However, the plans continue to be something that is imposed on an area from above. At best, there will be continual engagement between the ministry and the people in the plan area, and the plan itself written to be adaptive. However, there is no guarantee in the legislation that this will be the case. Given the scarce resources of government, a water sustainability plan may be seen as a way to solve a problem, and then move on. A plan would only be revised when it is clearly not doing the job it was meant to. It would be much better for the plan to be built so that those affected by the plan are engaged in an ongoing way in assessing its effectiveness and making adjustments where the effectiveness is shown to be lacking.

121 (1) Except as otherwise provided in this Act or by regulation, no compensation is payable by, and no legal proceedings may be commenced or maintained against, the government or any other person for or in relation to loss or damages arising from an effect on …

It is interesting that within a water sustainability plan, water users whose licences will be significantly affected can expect compensation, while if the government chooses to change licences, claims for compensation are expressly prohibited. If one is concerned with the cost of taking actions that have such impacts, such as reducing or temporarily suspending licences to secure environmental flows, then this seems to make sense. However, this may be somewhat simplistic.

If water users are confident that they will be compensated if government changes the terms of their licence, then they are far more likely to cooperate when such changes are contemplated. For example, if an irrigator is drawing water from a stream that has fish in it, then there is a risk that water levels will fall so low that the government will suspend or cancel licences to protect the fish. If the irrigator is confident in fair compensation, should this happen, then the fish in the stream are not a threat. Absent such compensation, the existence of fish in the stream creates a risk for the irrigator. If the irrigator can take actions that either eliminate the fish from the stream or interfere with the ability of the government to measure the existence of those fish, then the threat will be reduced.

Compensation also creates a sense of fairness that can foster cooperation. Water users recognize that each water course is unique. However, when a water user on one source can have their licence reduced while a similar water user on a different source doesn’t, it creates a sense of inequity. When people feel they are not being treated fairly, they are far less inclined to cooperate. This sense of fairness may also compromise inspection and data reporting. Government staff are community members as well, and if they know that a decision they make will adversely impact a water user in their community – imagine a small rancher who is just scraping by – then they may choose to look the other way. They may do so because they know the rancher, or because they know that they want to have a peaceable relationship with the ranching community. Either way, enforcement and data collection becomes inconsistent. The compensation clauses in the water sustainability plan portions of the act make sense, as they will help facilitate cooperation and compliance with the plan. Compensation provisions for other parts of the act that adversely affect water users would similarly improve cooperation and increase compliance.

134 The Lieutenant Governor in Council may make regulations for the purposes of section 121 [no compensation] respecting the payment of compensation by the government, including, without limitation, …

This is interesting. Section 121 expressly protects the government from compensation claims. This section explicitly states that the government can make regulations that specify compensation for many of the things that are listed in section 121. I guess what the government is doing is protecting itself from lawsuits in relation to compensation, while at the same time recognizing the importance of compensation. What it probably boils down to is that water users who are adversely affected by a change in their licence will have to accept whatever compensation that the government offers. The water sustainability act will not give them any protection.

6 (1) Subject to this section, a person must not divert water from a stream or an aquifer, or use water diverted from a stream or an aquifer by the person, unless

(a) the person holds an authorization authorizing the diversion or use, or

(b) the diversion or use is authorized under the regulations.

I guess this is the powerful one. Short, but includes the word ‘aquifer’. It gives the government the power to regulate groundwater as well as surface water. This is coupled with 5 (2), which vests the property right to groundwater in the government as well. Short but strong.

Follow

Follow

Thank you for your work here…my concern, shared with many other people, is that BC MOE Honourable Minister Mrs Mary Polak’s department doesn’t appear to have the capacity to implement the WSA or to do the necessary compliance monitoring and enforcement…so the WSA might look good on paper, as does the Mexican Environmental Legislation, but will be a paper tiger with little credibility on-the-ground, in-the-real world…

The devil is in the details. What will the regulations be? What resources will be made available to support implementation? Still a lot left to do.