I have been participating in a partnership project involving the Nepal office of the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) and the Okanagan Sustainability Institute (OSI) here at UBC. The project, “Preparing for an Uncertain Water Future in Nepal through Sustainable Storage Development,” was funded by the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA). CIDA no longer exists as an independent agency, being integrated into the department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada. This places support for international development more directly under ministerial control, and integrates that support with other foreign policy goals of the Canadian government.

I have been participating in a partnership project involving the Nepal office of the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) and the Okanagan Sustainability Institute (OSI) here at UBC. The project, “Preparing for an Uncertain Water Future in Nepal through Sustainable Storage Development,” was funded by the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA). CIDA no longer exists as an independent agency, being integrated into the department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada. This places support for international development more directly under ministerial control, and integrates that support with other foreign policy goals of the Canadian government.

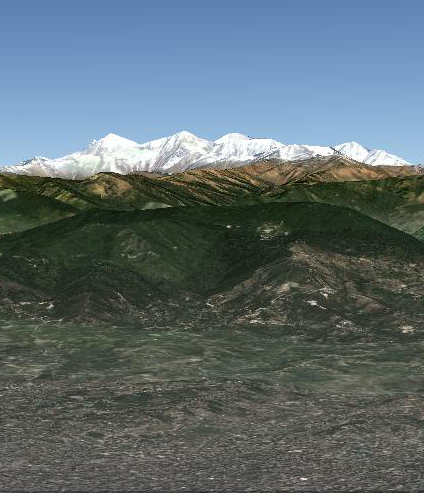

Nepal is a small country sandwiched between India on the south and China on the north. Its northern border joins some of the highest peaks in the world, including Sagarmatha (Everest), the worlds highest at 8,516 meters. Nepal is a small country, less than 900 kilometers long and less than 200 wide. Along the southwest border with India, elevations range between 60 and 180 meters above sea level, while most of the northern border with China is above 4000 meters, sometimes substantially so. The cordillera is punctuated in a couple of places by deep canyons, the floors of which are only 2000 meters above sea level, draining part of the Tibetan plateau. This elevation change occur over distances of less than 200 kilometers, the most extreme on earth.

Nepal is a small country sandwiched between India on the south and China on the north. Its northern border joins some of the highest peaks in the world, including Sagarmatha (Everest), the worlds highest at 8,516 meters. Nepal is a small country, less than 900 kilometers long and less than 200 wide. Along the southwest border with India, elevations range between 60 and 180 meters above sea level, while most of the northern border with China is above 4000 meters, sometimes substantially so. The cordillera is punctuated in a couple of places by deep canyons, the floors of which are only 2000 meters above sea level, draining part of the Tibetan plateau. This elevation change occur over distances of less than 200 kilometers, the most extreme on earth.

The images below show a horizon, simulated by Google Earth, as viewed from about 800 meters above Calgary and above Kathmandu, the capital of Nepal. Calgary sits at about 1100 meters above sea level, while Kathmandu is slightly higher at about 1300 meters. From Calgary, the 2970 meter peak of Mount Cornwall is just over 70 kilometers away, while from Kathmandu, the 7104 meter peak of Pabil is almost 80 kilometers away. The fact that Pabil rises almost four kilometers farther up substantially changes the horizon!

Nepal is a developing country, with more than 26 million people in an area that is less than five times the size of Vancouver Island, or about two and a half times the size of Nova Scotia. It has a gross domestic product (GDP) of about $1,200 per capita, when measured in terms of purchasing power (less than $750 at currency exchange rates). Here in British Columbia, our per capita GDP is more than $47,000. Nepal’s population has been growing at close to two percent per year for most of the 21st century, with a drop during the civil war in 2009. Life expectancy is less than 70 years, and more than 40% of the population is illiterate. It also falls in the worst 30% of countries in terms of corruption. Life expectancy in Canada is over 80 years, and we rank in the top five percent of the least corrupt countries.

Nepal has abundant water resources, having 7,296 m3 per person per year of renewable water. The US has renewable water of 9,847 m3 and Canada has 87,255 m3. However, Nepal lacks the resources to both make full use of the water it has and to protect the quality of that water. In urban areas, water supplies are often inadequate and not safe to drink. During the monsoon, flooding and damage to infrastructure can be substantial. Months later, many communities face water shortages. Within this context, our project sought to help identify those storage technologies that would best help rural Nepali people sustain their livelihoods in the face of the many challenges that they face.

What can we learn about water management in the Okanagan by working with people in Nepal? In spite of the substantial differences between Nepal and Canada, there are some similarities that stand out. Nepal is a mountainous country with snowfall serving an important role in sustaining dry season streamflow. Like the Okanagan, climate change will likely reduce snowfall and increase rainfall, leading to higher spring (monsoon) peaks and less water during low flow periods. Nepali communities, like communities throughout the world, struggle to find ways to work together on projects valuable to the community. Government intervention aimed at helping Nepali communities has sometimes had serious unintended consequences, a story not unfamiliar in Canada. Many of the challenges that Nepali academics and government officials identify – lack of communication between disciplines, lack of coordination and cooperation across departments, overlapping and confusing jurisdiction, public apathy and ignorance – sound surprisingly familiar. And, fundamentally, people in Nepal and people here in the Okanagan are looking for ways to sustain and enhance their quality of life in a complex, changing world. Over the next few months I hope to provide a bit more detail on the ways I think working in Nepal has provided insights valuable to water management here in the Okanagan.

Follow

Follow