The following comments were prepared for presentation in the “VI Cumbre de Ex-Presidentes: Institucionalidad Democrática e Inclusión Social,” organized by the Centro Global para el Desarrollo y la Democracia, Hotel Country Club, Los Eucaliptos 590, San Isidro, Lima, September 11, 2011.

The following comments were prepared for presentation in the “VI Cumbre de Ex-Presidentes: Institucionalidad Democrática e Inclusión Social,” organized by the Centro Global para el Desarrollo y la Democracia, Hotel Country Club, Los Eucaliptos 590, San Isidro, Lima, September 11, 2011.

Executive Summary

The Strengths of the Charter are that it:

– defined democracy as a right;

– encompassed more subtle threats;

– made democracy a condition of OAS membership.

The Weaknesses of the Charter are that it:

– did not recognize multidimensionality of democracy;

– was vague on what counts as an interruption/alternation of the democratic order;

– has very weak enforcement mechanisms.

Recommendations for improvements include:

– clarification of the meaning of interruption/alternation of the democratic order;

– creation of a democracy traffic light;

– establishment of a democracy inspector.

Introduction: The Strengths of the Charter

The Inter-American Democratic Charter, adopted by the members of the Organization of American States on September 11, 2001, represented three major steps forward with respect to the defense and promotion of democracy in the Western Hemisphere.

First, it established representative democracy as a right, and it defined the elements of democracy broadly to include “free and fair elections,” a “pluralistic system of political parties,” and the “separation of powers and the independence of the branches of government.” The Charter also recognized the “right and responsibility of all citizens to participate in decision relating to their own development” as a condition for the “full and effective exercise of democracy.” Despite references to participation, however, and notwithstanding objections by Venezuela, democracy was defined as a representative regime.

Second, the Charter broadened the understanding of threats to a democracy to encompass the more subtle challenges that had confronted Peru and other Latin American countries in the 1990s. For this reason, the Charter refers to “situations” that may affect “the democratic political institutional process or the legitimate exercise of power” (Article 18). Under Alberto Fujimori, for example, Peru had experienced democratic backsliding without recourse to the kind of conventional military coup that policy makers had in mind when they wrote of “sudden or irregular” interruptions of democracy in Resolution 1080 in 1991.

Third, the Charter reworked the compromise between non-intervention and democracy that was already implicit in the 1948 OAS Charter. This meant not only that the entire Hemisphere accepted democracy as the basis of membership in the OAS, but also that the most powerful states in the system, including the US, could not sponsor or accept non-democratic regimes within the OAS. It is worth recalling that the 1976 OAS General Assembly was held in Chile at the height of the Pinochet dictatorship.

The Problems with the Charter

From the outset, the Charter had three problems.

First, the meaning of democracy grew more contested after the Charter was signed in 2001, especially after a wave of left-wing governments emerged in the context of crises of representative democracy. Since that time, Latin America has undergone considerable democratic experimentation. Most governments (across the ideological spectrum) continued to regard free and fair elections as the cornerstone of electoral democracy, but many failed to uphold basic constitutional rules. In particular, judicial independence has often been undermined. A number of governments have promoted direct participation in an effort to make democracy more meaningful, but often in ways that did not reinforce representative institutions. Since democracy is a multidimensional concept, it is possible for progress along one dimension to be accompanied by backsliding along another. The consensus around the key elements of representative democracy in 2001 gave way in the face of a more diverse array of models of democracy.

Second, the meaning of an “unconstitutional interruption of the democratic order or an unconstitutional alteration of the constitutional regime” (Article 20) was left undefined. Despite efforts—both by scholars and policymakers—to specify what this language means, confusion often arose over when countries were not in compliance with the Charter. Even more crucially, the ambiguous phrase was followed by a key qualifier: the interruption or alteration of democracy would only enable the OAS to act if it “seriously impairs the democratic order in a member state.” That, obviously, would be a matter for political judgment. Yet the last decade has seen the growth of tensions within the OAS with respect to the how to exercise such political judgment.

Third, the Charter had very weak enforcement mechanisms. As a political document, it depended on the will of the member states, and they typically did not like to criticize each other. Moreover, the Secretary General needs permission to send a mission to investigate abuses of democracy (see Article 18). But, of course, the abuses of democracy are most likely to occur due to the behavior of the governments and leaders in question. Another way of putting this is to say that the Charter has a bias in favor of the executive: legislatures and courts have no standing in the OAS, and hence no formal role to initiate the enforcement provisions of the Charter.

Recommendations to Reinforce the Charter

In order to more fully realize the Charter’s potential as an instrument for flexible and preventive diplomacy, it needs to be reinforced. These changes would not necessarily require formal amendments to the Charter. They could take the form of codicils or complementary efforts in at least three general directions.

While recognizing the diversity of democratic regimes, it is necessary to establish the minimum features beyond which no country can be considered democratic. This also involves more clarity on what counts as a coup, and what must be done when a constitutional order has non-democratic features. As a point of departure, the 8 points outlined by former US President Jimmy Carter in his 2005 speech to the OAS might be formally adopted on a voluntary basis as a codicil to the Charter.

Mr. Carter’s 8 points include: “1. Violation of the integrity of central institutions, including constitutional checks and balances providing for the separation of powers. 2. Holding of elections that do not meet minimal international standards. 3. Failure to hold periodic elections or to respect electoral outcomes. 4. Systematic violation of basic freedoms, including freedom of expression, freedom of association, or respect for minority rights. 5. Unconstitutional termination of the tenure in office of any legally elected official. 6. Arbitrary or illegal, removal or interference in the appointment or deliberations of members of the judiciary or electoral bodies. 7. Interference by non-elected officials, such as military officers, in the jurisdiction of elected officials. 8. Systematic use of public office to silence, harass, or disrupt the normal and legal activities of members of the political opposition, the press, or civil society.”

Making assessments with respect to whether member states are in compliance with the Charter along the lines of Carter’s 8 points should be based on solid empirical evidence. The Inter-American system lacks robust monitoring and reporting on the state of democracy. Such reporting should be arms-length from both the OAS and member states, and should result in publicly accessible, peer-reviewed research. At the same time, the empirical research needs to be presented in a format that is useful for policymakers.

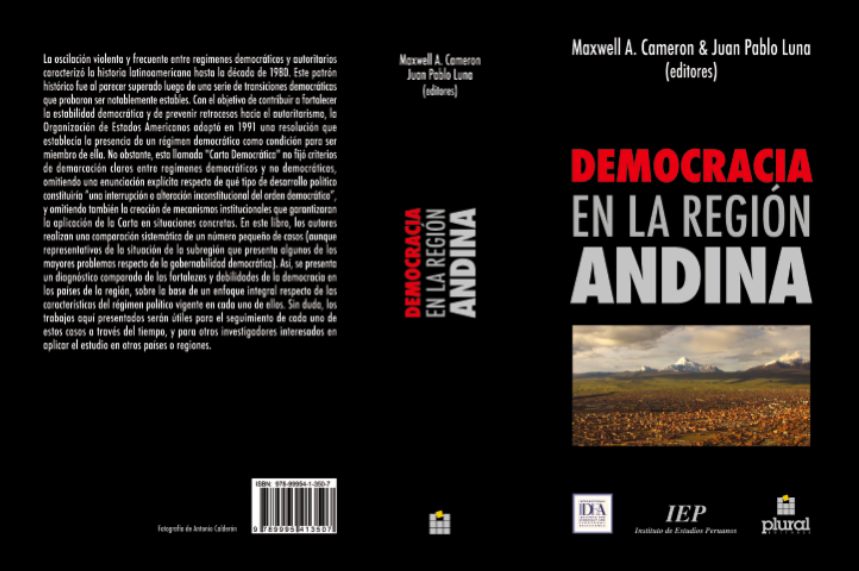

An effort to develop a mechanism for monitoring and reporting on the state of democracy in the Andean region was undertaken by a group of scholars under the aegis of the Centre for the Study of Democratic Institutions at the University of British Columbia, the Andean Commission of Jurists, International IDEA, and the Carter Center. Together, these groups created the Andean Democracy Research Network and commissioned a series of studies on the state of democracy in the Andean region. Over 20 scholars were involved from six countries. These studies adopted a common methodological template which examined not only the electoral and constitutional features of democracy, but also the issues of citizenship and participation that have become central to the debates on the quality of democracy over the past decade.

Monitoring would be most useful if it were to highlight those situations in which a member state is at risk of serious impairment of democracy. A “democracy traffic light” could usefully identify the political regimes in which such risks exist. Member states in good standing would be given a green light. There is one country in the Western Hemisphere that is unequivocally non-democratic, and which would be given a red light (Cuba). But there are a number of other regimes that have both democratic and authoritarian features. If the authoritarian features are sufficiently strong this may indicate the impossibility of holding elections that can be considered to be free and fair by the international community. Such regimes exist in a zone of indeterminacy between democracy and authoritarianism, and would be given a yellow light.

A yellow light would indicate the need for collective deliberations by OAS member states. Ideally, this would trigger the Chapter IV provisions of the Charter. Since this does not occur due to the Charter’s “Catch-22,” alternative institutional mechanisms are needed. For example, the Inter-American system could create a “democracy inspector.” The work of the democracy inspector would be similar to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in Honduras. A less ambitious version of the same idea would be a peer review mechanism. This might begin with the development of a compendium of best practices in democratic governance, an idea proposed by the Canadian government in the most recent General Assembly of the OAS.

Conclusion

The Democratic Charter is a work in progress. It represents an advance over previous instruments and has the potential to be use in proactive and preventive ways to reinforce democracy in the Western Hemisphere. At the same time, it is a flawed document that has a number of loopholes and vague provisions that need to be tightened and more sharply defined. Much of this can be done without amending the Charter, but it demands leadership with vision and energy, both inside and outside the OAS.