The elusive seminal paper

Do you ever get a brilliant idea, immediately followed by that nagging feeling of “someone must have already thought of this…”? In science, there is nothing worse than slaving away on a project and parading it in front of your peers, only to find out someone else did it better than you a few decades earlier. See Paul Vallett’s hilarious “science in reality” flow chart for an illustration of how this works. That nagging feeling can lead you to spend countless weeks reading obscure journals in search of the paper that scooped your precious revelation. In the scientific process, this paranoid frenzy is called the “literature review.”

If you’re very lucky, you find nothing; your genius is vindicated and your Nobel Prize awaits. If you’re like the rest of us, you will find a half dozen other scientists that pretty much did what you were going to do, except in their own fields. You accept your place as one of the pawns in the game of science and try to carve out your own mildly originally application of an old concept.

However, as you peruse some dark corner of the internet, you might find a grainy, scanned pdf of a paper written a century ago by some gentleman in tweeds who wrote manuscripts with pen and ink and actually got to do field work. It quaintly lays out everything you wanted to say, but hadn’t thought of yet. Perhaps it outlines a technique that was never taken up in its time, but is perfect for your project. This is the coveted Seminal Paper. In a time when a paper is considered old news if it was published more than 5 years ago, it is refreshing to find new relevance in a forgotten work. It can be a poignant link across generations, and a reminder to think outside the current hype cycle. It also gives you some shoulders to stand on.

I’m starting a master’s degree in the Aitken Lab. My project is about the role of interannual climatic variability in mediating or exacerbating the impacts of climate change on trees and forest ecosystems. A lot has been written in the climate change literature about interannual climatic variability, but the emphasis within forest ecology is still very much on thinking of climates in terms of averages that change slowly over time. My idea is that thinking of climates in terms of averages may be more misleading than helpful. Perhaps the magnitude and sequence of different conditions experienced from year to year are more important to forests than the average of these conditions. This is a compelling thought, but it also seems really obvious. Someone must have already thought of this!

During my literature review over the Christmas holidays, I came across a 1934 paper called “Climatic Years” by Richard Joel Russell, an American geographer. Russell argues that climates are not fixed in position, but instead shift in location from year to year. A location may experience one climate type one year and another climate type the next year. The climatic-year approach classifies climates in terms of conditions that may be experienced in any given year. Climates of individual locations are characterized by the relative frequency of different climatic years over longer periods of time. This is a fundamentally different approach than typical climate mapping, which assigns a climate types to a locations based on that location’s average climatic conditions. Russell’s climatic year concept embraces variability and its ecological importance.

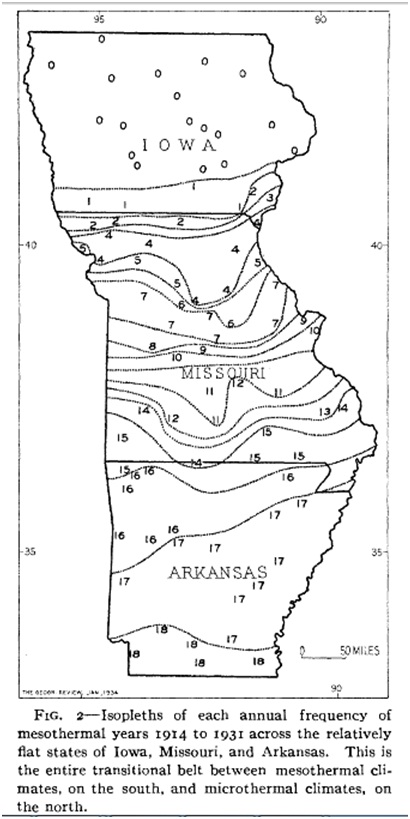

Figure 1: A figure from Russell (1934) showing his approach to mapping climatic transitions using the climatic year concept

Russell primarily uses this approach to characterize transition zones between climatic classification units. Core areas are predominated by a single climate-year type. Transition zones can be identified as areas that oscillate between one classification unit and another from year to year. Furthermore, the relative influence of each climate-year type can be mapped, eliminating the need to establish an artificial spatial boundary between the two climate classification units (Figure 1). This approach to mapping climate without resorting to artificial fixed boundaries is novel to forest ecology even today.

Russell’s climatic year concept is obscure in the scientific literature. It is only cited only 15 times in Web of Science. The climatic year concept is not even mentioned in a detailed biographical memoir of R.J. Russell published in 1975 by the National Academy of Sciences. It appears that the climatic year concept fell flat during Russell’s lifetime, likely due to the mainstream assumption that climates are unchanging over scales of decades. Nevertheless, it is clear that Russell’s approach has come of age. It appears to be gaining some traction within the American geographical tradition as an effective way to assess climate variability and change (e.g. Grundstein (2008) and Kunkel and Changnon (2003)). I will certainly be standing on Russell’s shoulders for my own research.

Some juicy quotes from Russell (1934)

In addition to providing the climatic year concept, Russell’s 1934 paper also includes some beautiful passages of subtle thinking and ecological wisdom. Here are some of my favourites:

On ecologically critical thresholds along a continuous climatic gradient:

“If we assume that gradual transitions in nature, here and there, encounter important critical limits, it is clearly these we seek in climatic definitions. If these limits are inconstant in position from one year to the next, we have the reason why climatic boundaries are transitional zones.”

On different necessities and approaches for considering extremes (“the unusual experience”):

“In [some] cases a climatology of extremes is more significant than one based on normals. On the other hand, many unusual experiences are not expressed in landscape-at least for significant periods of time. Mature plants are less likely to succumb to the vicissitudes of climate than are young ones. Though an occasional desert or tundra year may upset vegetational balances temporarily, recurrence at such a rate as once a century very likely has little bearing on the distribution of forest or grassland. Yet, if the recurrence is so frequent that individual plants are prevented time after time from reaching sufficient maturity to withstand such extremes, it becomes highly significant. The westward extent of forest toward the Great Plains of the United States is more probably related to the recurrence of desert years than it is to the distribution of normal precipitation. While some unusual experiences deserve emphasis in certain climatic studies, others should be deleted from the records rather than averaged into normals.”

On the artificiality of boundaries in climate mapping:

“The substitution of a cartographic line for a transitional zone in nature should be clearly understood… There is real merit in the omission on climatic maps of a detailed grid or other means for the close identification of boundary positions, for the reason that the reader is thereby more or less forced to recognize boundaries as transitional zones.”

On the relative importance of core (“nuclear”) zones vs. transition zones in climate mapping:

“While theoretical reasons possibly exist for the recognition of climax climatic landscapes in terms of very small areas, thereby leaving most of the earth’s surface within transitional zones, the ends of geographical inquiry are better served by the adoption of climatic definitions sufficiently broad and flexible to admit more extensive type regions and narrower transitions.”

On different ecological meanings of climatic oscillations over different periods of time:

“The student of successive landscapes may require a successional climatology involving a whole series of climatographies, each based on possibly less than twenty-year periods. As we dissect the landscape into its component groups of forms, we find that individually these demand longer or shorter periods for the reason that they travel toward equilibriums at differing rates. During a twenty-year interval, ten desert years-occurring as a rather unusual experience in terms of the events of the past century-probably alter vegetation much more than land, drainage, or soil forms.”

References

Grundstein, A. (2008). Assessing Climate Change in the Contiguous United States Using a Modified Thornthwaite Climate Classification Scheme. The Professional Geographer, 60(3), 398–412.

Kunkel, K. E., & Changnon, S. A. (2003). Climate-years in the true prairie: temporal fluctuations of ecologically ctritical climate conditions. Climatic Change, 61, 101–122.

Russell, R. J. (1934). Climatic Years. Geographical Review, 24(1), 92–103.