While visiting the University of Wisconsin – Madison, two days ago

UW’s Zoological Museum curator handed me a large box and disappeared behind a hobbit-like door leading into the side of a grassy hill leading up to one of the campus’s buildings. I peered into the box: a mangle of delicate swan bones covered in dried pinky-red flesh. I might have dropped it if it wasn’t so feather-light. We – a group of grad students, artists, poets, and professors gathered for the Taking Animals Apart conference – had just spent an hour checking out the museum’s collection of specimens: articulated and disarticulated skeletons, shelves lined with jars of preserved animals, and taxidermied mounts and full animal bodies. Noteworthy specimens: a giant beaver skull (like below) found just a few miles from the university campus in a peat bog, and a drawer full of stuffed passenger pigeons lying tidily side by side on a large pillow.

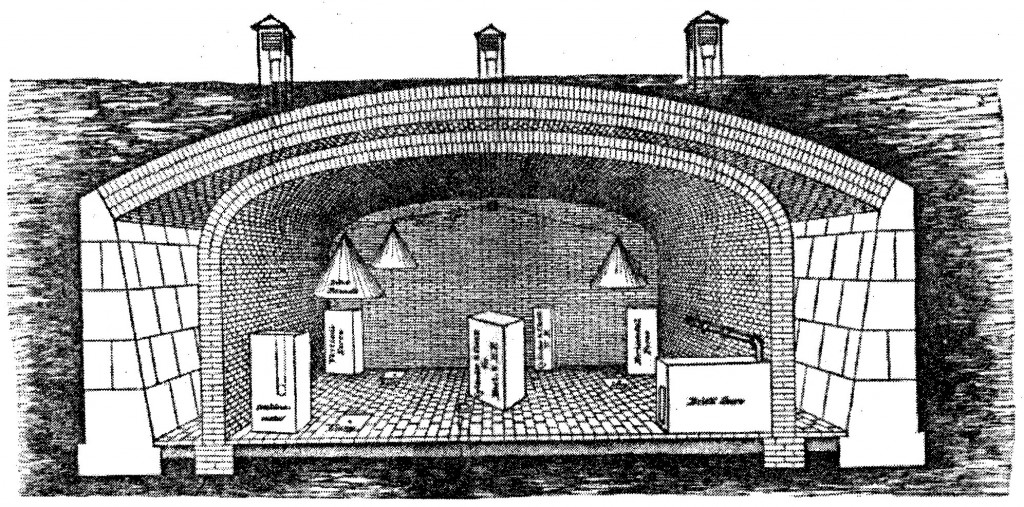

When the curator returned we followed her into the dimly lit, narrow, low ceilinged corridor. The air became increasingly steamy and hot, the walls dripping with condensation, as we snaked out way underground. With a flourish the curator opened a second door and we entered a small cavern thick with steam: the university’s private dermestid beetle colony. Or, flesh-eating beetles.

Spotting two hefty scurrying bugs I exclaimed: “they’ve escaped!” Thankfully only the nearest person to me heard, and corrected me: “uh, those are cockroaches”. Oops (thanks, rural upbringing!). The beetles are much smaller than cockroaches, and filled several raised stainless steel tanks the size of large trunks. Lifting the lid, the curator placed the swan bones in one container and misted the container with water. Within a few days, she explained, the bones would be picked spotlessly clean by the beetles so that only minor prep is needed before the bones can be catalogued into the museum’s research collections.

Dermestid colonies are still used extensively by museum like the UW’s (and by taxidermists). It was hard to reconcile the clinical, sterile, and meticulously organized collection of unblemished, labeled organisms in the museum’s collection with the dank, feral world of the underground flesh-eating beetle colony. A lot of work goes into maintaining the beetles as a living colony that transforms messy remains of death into bones stripped clean and ready to be placed into taxonomically categorized drawers. Both of these worlds – the underground beetle colony and the floors of cabinets full of specimens – gave whole new meaning to Roland Barthes’s comment that “all classifications are oppressive.” I was reminded also of how “taking animals apart” often occurs in a largely hidden space using messy practices, like butchering meat or milking dairy cows. The end product is clean, largely divested of the blood, feces, sweat and bugs that formed it. Our general collective ignorance of these processes is in some ways a classic form of commodity fetishism, wherein the commodity is treated like “it has a life of its own” (as Marx famously remarked) rather than as a social product created through multiple (and usually highly unequal) relations and processes. But animals that are taken apart do or did have lives of their own, bringing a whole new set of ethical and political questions to the fore, and reminding us that life, too, can be doubly erased by the end product of taking animals apart.