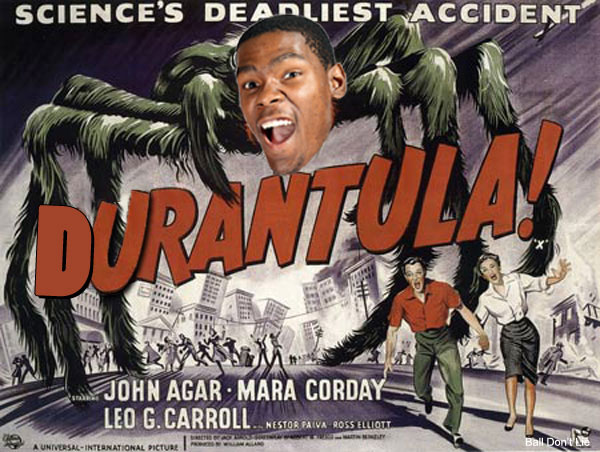

It was hard not to notice the importance of Kevin Durant’s arms over OKC’s incredible comeback against the San Antonio Spurs in the NBA semis. The things were everywhere — intercepting passing lanes, flicking 3 pointers, leading the break. The 6’9 shooting guard reportedly has a 7’5 wingspan, which puts his extensions in rare company for a player at any position. It is for these reasons and the inviting fact of his last name that the multi-skilled scoring machine often goes by nickname alone: “Durantula.”

There are all sorts of great nicknames in the NBA, from the domestic “Hibachi” (Gilbert Arenas), to the goofy “Round Mound of Rebound” (Charles Barkley), to the supremely self-evident — “#23.” Even if we go by one category — say, ‘animate nicknames’, for the sake of this blog’s focus — the NBA offers much in the way of choice. Many fall in the ‘animal-hustle’ category: Jerome “Junkyard Dog” Williams; Dan “the Horse” Issel; Craig “Rhino” Smith; Ken “The Animal” Bannister. Another broad category is ‘animal-predator’: While Trevor “Cobra” Ariza packs a poisonous punch for opposing defenses, far deadlier is the “Black Mamba,” aka Kobe Bryant (though we should also note his dialectical opposite, Brian “White Mamba” Scalabrine, is anything but). A third category is the animal-as-cartoon, like Damon “Mighty Mouse” Stoudamire, giving you way more than his 5’9 frame would suggest, or Toni “The Pink Panther” Kukoc who was smooth and Euro-effeminate, or Jim “Kangaroo Kid” Pollard’s name should need no explanation. A fourth is not ‘animal’ but bio-mechanical: here we have LeBron “L-Train” James, Vince Carter (“half man half amazing”), Dwight Howard (“Superman”), and the grandaddy of the self-appointed NBA nickname, Shaquille “Shaq Diesel” O’Neal (aka “Shaq Fu”, “The Big Aristotle”, “Superman”, “The Big Maravich”, “The Big Felon”, “The Big Cactus”, “The Big Cordially”, and “The Big Shamrock”). By far the best grouping is ‘miscellaneous animal.’ My all time favorite belongs to the mysterious Bill Mlkvy, who played less than one season in 1982, and was called “The Owl without a Vowel” for what seem to be purely mnemonic reasons. The jury may still be out on the Loch Ness monster but it certainly ain’t about the game of John Brockman, aka “The Brockness Monster” (because he so rarely surfaced on the court during games). Streetball legend Earl “the Goat” Manigault was neither of the NBA nor the animal kingdom, but he was considered by some to be the Greatest of All Time (G.O.A.T).

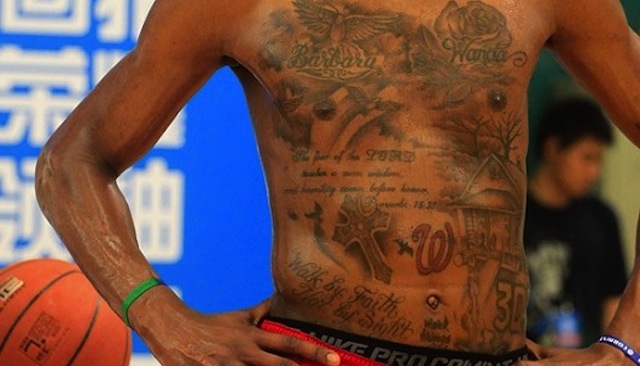

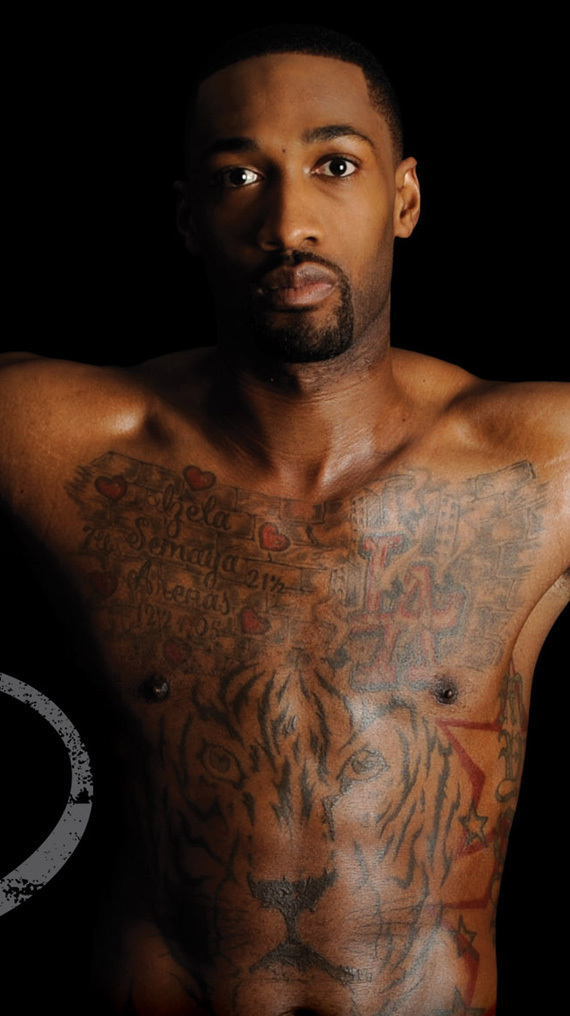

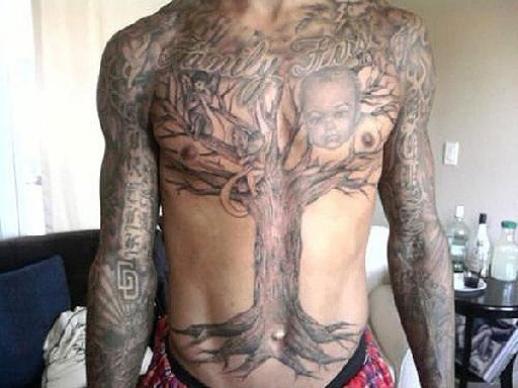

Now the world of NBA nicknames is interesting enough, but it relates to something I find to be much more so: the world of NBA tattoos. Back to “Durantula” here. The OKC star was recently involved in something of a controversy over his secretive deployment of ink. His spider arms are clean, as the photo indicates, but his chest and back are all tattied up. In fact, there’s a fascinatingly weird world down there: a Wallgreens logo, a sort of ‘Little House of the Prairie’ with a pioneer home, trees, and a baby Durant; some scripture; Wanda mother’s name, a cross… there’s also a massive state of Maryland on his back. Durant isn’t alone in his choice of unsual torso tatts — Gilbert Arenas has the face of giant tiger across his chest (with black nipples for eyes); Monta Ellis recently inserted a Tree of Life rendering that extends across his arms; and in what is perhaps the ugliest of them all, Andrei “AK-47” Kirilenko has the World of Warcraft dragon emblazoned across his entire Russified backside.

So why would Durant hide his? They have been described by some as “business tattoos,” the insinuation being that one of the league’s biggest rising stars doesn’t want to jeopardize his marketability by marking up his lineaments. Less than 15% NBA players had tattoos at the outset of the 1990s. By 2002, the number spiked to 50%. Many of the NBA’s other highly marketable stars — Lebron, Wade, Kobe — are all filled with exposed tattoos, but Durant can have a squeaky clean image if he wants it. Its an interesting decision on his part — and one many of his best rivals — Blake Griffin, John Wall, and Durant’s teammate, Russell Westbrook — have chosen to follow as well.

In a sports world full of canned promo and potted interviews, the highly regulated body of the NBAer is a fascinating site for the convergence of all sorts of cultural-economic forces — from health insurance to hip hop. Tattoos reveal how iterative and self-reflexive the branding process really is — and how much more is at stake than simplistic accounts of self-commodification would suppose. In a now decade-old piece for the Village Voice, David Shields notes that players of body-contact sports opt for tattoos far more than those in non-contact sports (eg. baseball, tennis). There is no better example of this than the NBA. For many NBA players, tattoos describe maps of self-narrativization that speak in ways they never would. A wide array of tropes are written across the skins of any number of players: the grieving son, the grieving sibling, the family breadwinner, the state hero, the shoe rep, the former thug, the current thug, the rich man, the black man, the spiritual man. And once the ink dries to face the world, tattoos combine with the nicknames, the marketing of the nicknames through the shoes (like Durant’s Adidas Predator), the trademark spin-moves, the overly-speculated upon injuries, the Gatorade consumption — to spiral outwards to the relatives, the fans, the hangers-on, the agents, the video-game designers, the executives, and so on. NBA bodies occupy a site within something largely understudied in the social sciences despite its centrality to American social life: the intersection of race, representation, and sport.

No one player was more responsible for the mainstreaming of the NBA tattoo than Allen Iverson (my personal G.O.A.T., for what its worth). Iverson, whose cat-like quickness made him unguardable, and at six feet 165 pounds has been called the “pound-for-pound most gifted and fearless guard to ever play pro basketball,” entered the league in 1996 with single marking on his right arm and a two-word inscription beneath it. The bulldog tattoo branded him as a Georgetown Hoya, and the “the Answer” became both his self-appointed nickname and best selling shoe. He was product of a 15 year old mother and had two counts of gun-possession to his name before he turned 21. While many players’ would permit theirs some wackiness after they got rich, Iverson’s tattoos remained painfully self-revealing: “F.A.M.E” (Fuck all my Enemies); “RA Boogie” (a childhood friend who was shot); “Only the Strong Survive”;“Loyality;” “Money Bagz.”

Over the course of his NBA career, Iverson’s body got many more tattoos and became involved in many more controversies — over skull-caps and cornrows, jewelry and rap skills, and somewhat hilariously — practice. His 2001 outburst upon hearing that the NBA’s Hoop Magazine had airbrushed his tattoos off a photograph of him for a magazine cover, was memorable and justified: “That’s not right. Hey, I am who I am. You can’t change that. Who gives them the authority to remake me? Everybody knows who Allen Iverson is. That’s wild. That’s kind of crazy…. They don’t have the right to try to present me in another way to the public than the way I truly am without my permission. It’s an act of freedom and a form of self-expression.”

Iverson played fearlessly and wildly selfishly at times, winning scoring championships despite limited surrounding talent. He played through a tailbone contusion, a right shoulder dislocation, multiple broken fingers, and fractured left hand. Like his tattoos, Inverson’s body was used to sell other products and to be consumed as one. It will bear these decisions for the rest of its life cycle. Now 38 and unable to secure another NBA contract despite a stated willingness to play anywhere, Iverson will have watch the Durantula & Co. finals as a spectator. Though its widely speculated he really needs the money, its a shame no one signed him because you know he would have given his all regardless. As much as I am awed at the physical abilities of these players, nothing replaces their story-lines.

One response to “Storylines”