This board game is inspired by Edo period travel and the idea of famous spaces. Today, as tourists we often travel to see the sights and have specific foods we want to try and places we want to explore. Major temples are placed on the board game like Ise Shrine and Mishima Taisha. Other iconic places are mentioned in the good luck and bad luck spaces regarding food famous to the lands. High status women in the Edo period would often travel to shrines and temples to receive blessings or to regain some sense of independence. This factor was inspiration for the premise of the trip, women travelling with attendants and trying to explore and see the places they perhaps read about in novels or in poems.

Rules

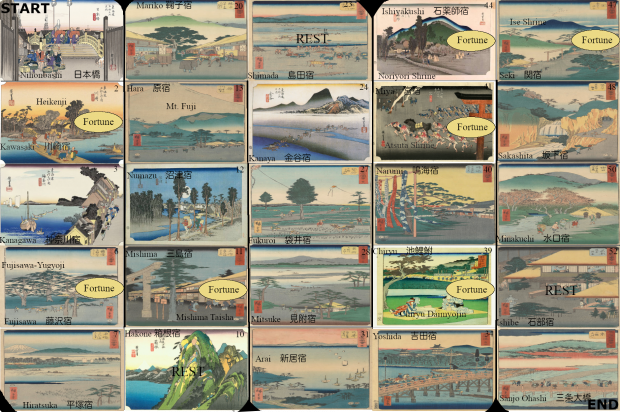

- You start at Nihonbashi in the top left and move down and up the board following the numbers in the top right corner of each square until you reach Sanjo Ohashi at the end.

- Roll a single dice to determine initial luck at the beginning of the game. You can re-roll your luck at the Fortune spaces at shrines marked on the board. 1-3 is Good Luck. 4-6 is Bad Luck.

- At REST spaces, you must stop.

Good Luck & Bad Luck

Good Luck

- Kawasaki: You receive a blessing at Heikenji and feel encouraged for the journey to come.

- Kanagawa: You stop at Sakuraya for tea. The tea stem floats upright, a sign of good luck.

- Fujisawa: You visit Enoshima Island.

- Hiratsuka: You pray for Okiku’s spirit from the ghost story “The Dish Mansion at Bancho” and she is finally at peace.

- Hakone: You take a break and enjoy the onsen.

- Mishima: You visit the abandoned Yamanaka Castle and reminisce in history.

- Numazu: You find extra coins in your pocket. How lucky.

- Hara: You gaze at Mt. Fuji and feel revitalized in its spiritual presence.

- Mariko: You make it in time to get a bowl of Mariko’s famous bowl of yam soup.

- Shimada: The weather is in your favour and low tide to cross the wading water.

- Kanaya: You pay someone to help you across the river.

- Fukuroi: You pass by the path to the 3 major temples are feeling content.

- Mitsuke: Your soba is just as delicious as expected. It was worth the trip.

- Arai: The winds are on your side as you sail. Move +1 move on next turn.

- Yoshida: You appreciate the sights over the bridge. It is one of very few thanks to the Tokugawa regime.

- Chiryu: You admire the pine trees growing along the Tokaido.

- Narumi: You buy one of Narumi’s famous tie-dye fabric.

Miya: You arrive in time to witness the Atsuta Festival and have a lovely time. - Ishiyakushi: You purchase some manjuu and are inspired to write a tanka.

- Seki: Ise Shrine, the home for Amaterasu, you receive a blessing, and the rest of your journey is filled with sunshine.

- Sakashita: The wind is behind you and you make it through the Suzuka Pass with ease.

- Minakuchi: You stop by Daitokuji and visit the rock that Tokugawa Ieyasu sat.

- Ishibe: You stay at the Kojima honjin and relax before the last stretch.

Bad Luck

- Kawasaki: You trip, and your sandal strap breaks. A worried feeling follows you.

- Kanagawa: You stop at Sakuraya, the tea house but the cup splits in half. A bad omen.

- Fujisawa: You’re refused access to Enoshima Island. What a shame.

- Hiratsuka: You are haunted by Okiku’s ghost from “The Dish Mansoin at Bancho” ghost story. Your shoulders feel a little heavier.

- Hakone: You stub your toe and are bleeding. Your trip to the onsen is cancelled now.

- Mishima: Your guide abandons you. You’re on your own now.

- Numazu: You see a tengu off in the distance. This could be trouble.

- Hara: The view of Mt. Fuji is blocked by grey foggy clouds.

- Mariko: The store runs out of yam soup right before you can get a bowl. How unfortunate.

- Shimada: The rains flood the river, and you have to wait at the inn for another night. Skip 1 turn.

- Kanaya: Your belongings are washed away in the river.

- Fukuroi: You reach the temple gates but are turned away.

- Mitsuke: Your soba is soggy and you’re disappointed.

- Arai: The winds are against you and the travel is slower than normal.

- Yoshida: Construction on the bridge makes you lose a day of travel. Skip 1 turn.

- Chiryu: You attend the horse market but do not have enough to buy one.

- Narumi: You spill tea and ruin the tie-dye fabrics you were hoping to bring home.

Miya: You’re pickpocketed during the Atsuta Festival and lose your spending money. - Ishiyakushi: Your stomach feels unsettled, perhaps the manju from the stall gave you food poisoning.

- Seki: You are stopped at the Ise Suzuka Barrier and your food supplies are taken from you by officers in an inspection.

- Sakashita: The weather in Suzuka Pass is too intense and your progress is slowed down.

- Minakuchi: You are stopped by soldiers on your way past Minakuchi Castle.

- Ishibe: The weight of the trip has tired you out and you rest an additional day at the honjin.

Nihonbashi as a starting place felt to be key as it was seen as the center of Edo. Nihonbashi was positioned at a central crossroad for those entering and exciting the city. Its presence as a popular urban space grew in the late Tokugawa period and images of the bridge came to include people crossing and also the movement of goods into the city (Yonemoto, 1999). I thought this would be fitting to the start of this journey. Mount Fuji has been a point of cultural focus and seen as a sacred mountain for Japanese people. Climbing the mountain for religious enlightenment became popular during the Edo period (Sugimoto & Koike, 2015). It had been a place of worship from a distance and very revered by people in the city of Edo. Rather than going themselves, people would pay others to go in their stead and climb the mountain for their blessings. This religious pilgrimage is suggested as the roots for the modern travel to visit Mount Fuji (Matsui & Uda, 2015). Mitsuke-juku was a place known for its lodgings and restaurants. People would come from far away to have soba in Mitsuke before taking the ferry across the water. Atsuta Shrine close to Miya-juku is another important shrine for Japanese mythology. The shrine houses the sword of Susanoo no Mikoto, Amaterasu’s brother who is the god of storms. Atsuta Shrine is a cannot miss stop for those who wish to reminisce about Japan’s mythology, and it is an important stop right before Ise Shrine. Ise Shrine has been a very important religious place in Japanese history. Seki-juku is very close to the shrine and as this game’s main focus is to visit shrines along the Tokaido, I thought it would be a must-see place to visit for any traveler. The pilgrimage to Ise has been taken for centuries with poems written on the subject such as A Journey to Ise (1686). The Ise shrine is dedicated to the sun goddess Amaterasu among others. There were bustling tea stores, inns, and shops around the shrine in the Edo period that were thanks to the high pilgrimage culture at the time. Ise mandalas were placed at the shrine to show how to perform prayers for pilgrims and depict maps of the shrine area (Hardace, 2017). Sanjo Ohashi, like Nihonbashi in Edo, is another centre of cultural importance. Bridges as a symbol of connecting spaces and connecting people felt like the ideal end point for the journey. It was built in 1590, over the Kamo River which divides Kyoto in two. It held significance to Tokugawa Hideyoshi who had it built with stone pillars to replace the old, unreliable timber bridges (Stravos, 2014). It is an important landmark in Kyoto and a point of crossing to get to the other places of interest like the imperial palace or Nijo Castle.

References

Hardacre, H. (2017). Edo-period shrine life and shrine pilgrimage. Shinto: A History. Oxford University Press.

Matsui K., & Uda, T. (2015). Tourism and religion in the mount fuji area in the pre-modern era. Chigaku Zasshi, 124(6), 895-915.

Sugimoto, K., & Koike, T. (2015). Tourist behaviors in the region at the foot of mt. fuji: An analysis focusing on the effect of travel distance. Chigaku Zasshi, 124(6), 1015-1031

Stavros, M. G. (2014). Kyoto: An urban history of japan’s premodern capital. University of Hawaiʻi Press.

Yonemoto, M. (1999). Nihonbashi, edo’s contested center [ie centre]. East Asian History (Canberra), 17(17-18), 49-70.