by Ziying

- Rinsenji temple

The place was where Tsuneno born. In Stranger in the Shogun’s City, once the baby lived for seven days, then it would be time to celebrate and to give her a name (Stanley, 2020).

Rinsenji temple [Digital image]. (2018). Retrieved March 29, 2021, from

https://www.google.com.hk/search?q=rensenji+temple&newwindow=1&safe=strict&hl=z

hTW&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiHwMXU3NTvAhXBJzQIHeryBP

8Q_AUoAXoECAEQAw&biw=1440&bih=739.

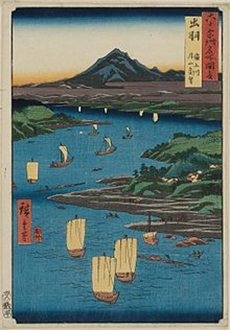

- The Oishida in Dewa province

In 1816, Tsuneno left Rinsenji for the first time. She was headed to an inland river town called Oishida in Dewa province, in the north. In the winter, the fir trees, encased in heavy snow, would look like grimacing monsters frozen to the hillsides. It was a difficult journey from Ishigami village to Oishida, over 180 miles. Tsuneno could get there by boat, sailing up the Sea of Japan coastline and then upriver. (Stanley, 2020). She was going to be married and she knew that girls of her status could not select their own husbands.

The Oishida in Dewa province [Digital image]. (n.d.). Retrieved March 29, 2021, from

https://www.google.com.hk/search?q=The+Oishida+in+Dewa+province&newwindow=1&

safe=strict&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjS9YHktfvAhXLi54KHed8C

yQQ_AUoAXoECAEQAw&biw=1440&bih=739#imgrc=qYpHWlrD5tNTwM

- Joganji temple in Oishida

Stanley, A. (2020). Joganji temple in Oishida [Screenshot]. Retrieved March 29, 2021, from

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5SZl0zTZO_w.

This is where Tsuneno experienced her first divorce. A divorce wasn’t necessarily a catastrophe. Women who divorced in their twenties almost always remarried, but those who were older struggled. Tsuneno was twenty-eight and just on the edge of this possibility (Stanley, 2020).

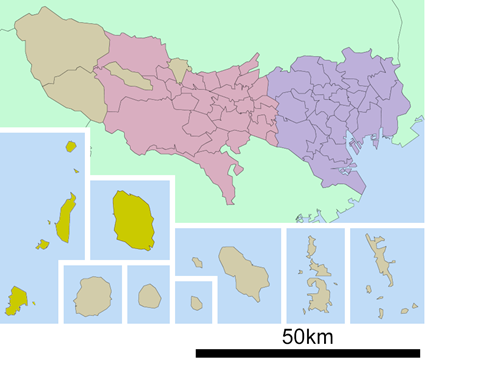

- Oshima

The village where Tsuneno’s second husband lived. Oshima Village hosted a market three times a month, and it was a stop on a minor highway leading through the mountains. In summer, when Tsuneno arrived, travelers and packhorses were still coming through, bringing news with them. It would be much quieter in winter, because the road would be impassable (Stanley, 2020).

Oshima [Ōshima Subprefecture]. (2015). Retrieved March 29, 2021, from

https://www.google.com.hk/search?q=%C5%8Cshima,+Tokyo&newwindow=1&safe=stri

ct&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwizx7qq_NnvAhURr54KHfUNBsIQ_A

UoAXoECAEQAw&biw=1440&bih=739#imgrc=MGDTgW4M1aZZSM.

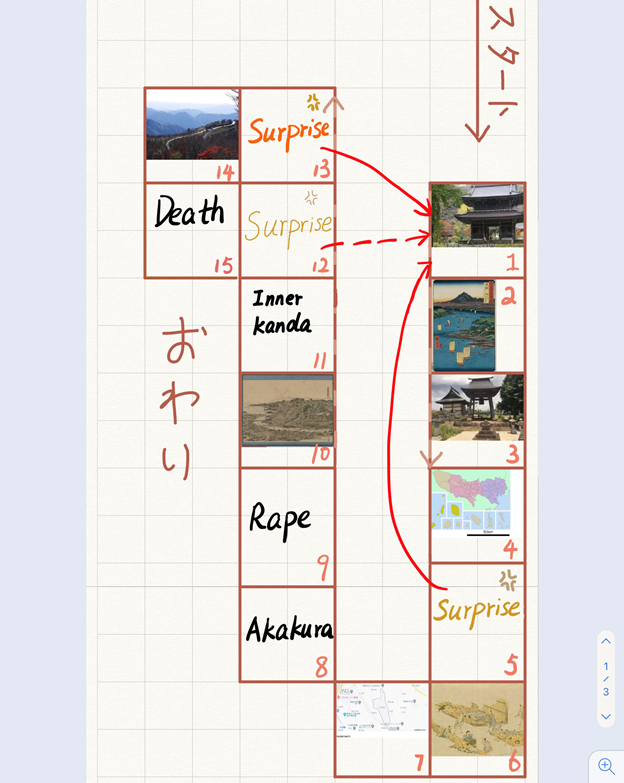

5. Surprise

- Tenpo Famine

During Tsuneno’s second winter in Oshima, she watched her neighbor’s struggle. Farmers brought in less than half the usual rice crop, and the soybean harvest was so bad that no one could make miso. Tsuneno was in no danger of starving, but she wasn’t entirely sheltered. Her husband, Yasoemon, had spent all four years of their marriage waiting in vain for something to change.

Tenpo Famine [Digital image]. (n.d.). Retrieved March 29, 2021, from

https://www.google.com.hk/search?q=Tenpo+Famine&newwindow=1&safe=strict&tbm=i

sch&source=iu&ictx=1&fir=EclhumhKOH0hRM%252CfBj552VNfdGcYM%252C%252

Fm%252F08c5dp&vet=1&usg=AI4_kRXQWZhYH87X9Df_cblwaMJBemg&sa=X&ved

=2ahUKEwijhOm_dnvAhUUpZ4KHSWWBCIQ_B16BAgZEAI&biw=1440&bih=739#i

mgrc=EclhumhKOH0hRM.

- Inadamachi

Tsuneno was thirty-four years old and married her third husband in Inadamachi. In midwinter, while the villages were sleepy, waiting for the thaw, Takada felt alive. The spring would be blinding, a sudden flood of sunshine after months of dim, filtered light. In the end, Tsuneno’s third marriage lasted four blurry moths. She was divorced before the last of the snow melted (Stanley,

2020).

Inadamachi [Map]. (2021). Retrieved March 29, 2021, from

https://www.google.com.hk/search?q=Inadamachi&oq=Inadamachi&aqs=chrome..69i57j6

9i60l3.1349j0j4&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8.

- Akakura

Tsuneno and her travel partner Chikan stayed there for a few nights and prepared for the rest of their journey (Stanley, 2020).

- Rape

Tsuneno didn’t have the words to describe sex with a man she would not have chosen, under circumstances she couldn’t control (Stanley, 2020).

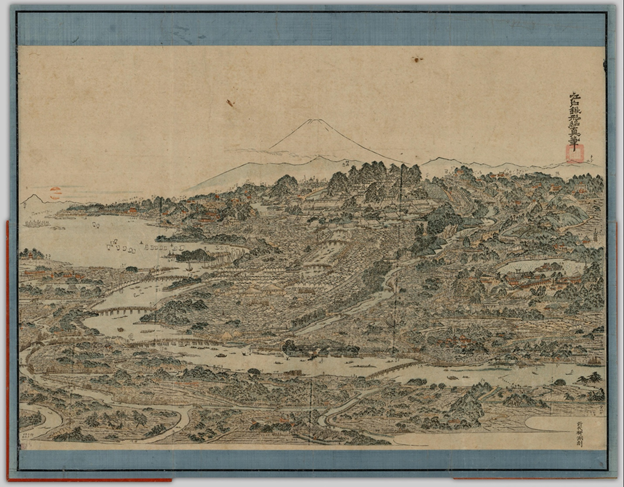

10.The Edo

People in Edo were everywhere, carrying palanquins in the streets, fighting fires, pulling handcarts, and raising scaffolding. Theirs was the common fate of the migrant: to make the city work without ever quite belonging.

Shōshin, K. (1803). Edo meisho no e [First edition]. Cover attached. This is the first edition; a facsimile of a later edition engraved on another woodblock is reproduced in 日本古地図大成 Nihon kochizu taisei, pl. 77, exposition volume, p. 76. Cited in: WSN; 142]. Retrieved March 29, 2021, from

https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/tokugawa/items/1.0216039#p0z-5r0f:The%20Edo

11.Inner Kanda

Tsuneno’s immediate destination lay in the western reaches of Inner Kanda, in a crowded, nondescript neighborhood that backed up against the moat of Edo castle (Stanley, 2020).

12. Surprise

13. Surprise

14.Minagawa-cho

Tsuneno spent her first night in the city. People all over Edo were remarking on the warm start to the winter, but Tsuneno had no nightclothes and no futon. She had no extra clothes. She had no money. Chikan was a useless liar, and Sohachi was threatening to send her to work as a maid (Stanley, 2020).

Minagawa-cho [Digital image]. (n.d.). Retrieved March 29, 2021, from

https://www.google.com.hk/search?q=Minagawacho&newwindow=1&safe=strict&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjorojwg

9rvAhVGj54KHZFTANUQ_AUoAXoECAEQAw&biw=1440&bih=739#imgrc=04GUY7

BeuJtOJM.

15.Death

Tsuneno died a few weeks later. She had been sick for nearly three months by then. If Tsuneno had lived a little longer, she would have seen a new city, Tokyo, emerge from the destruction (Stanley, 2020).

Tsuneno died, but her momentum didn’t.

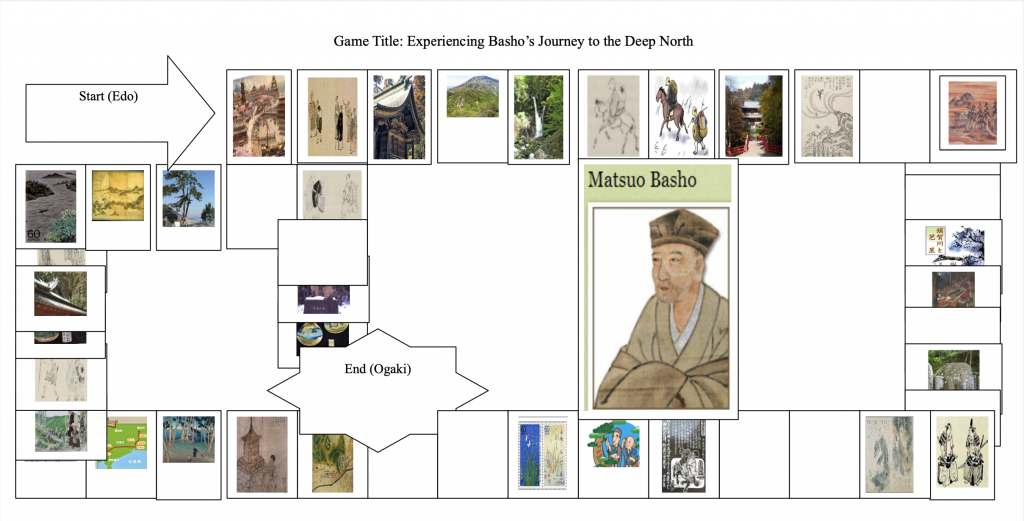

Commentary

The main character in this game is Tsuneno, a figure of Stranger in the Shogun’s City. The background of this game is the early 19th century. The whole journey is designed based on Tsuneno’s travel route. To be specific, the game starts from where Tsuneno was born and ends where Tsuneno died (with some cuts within her journey for the purposes of this game).

Instructions for game play

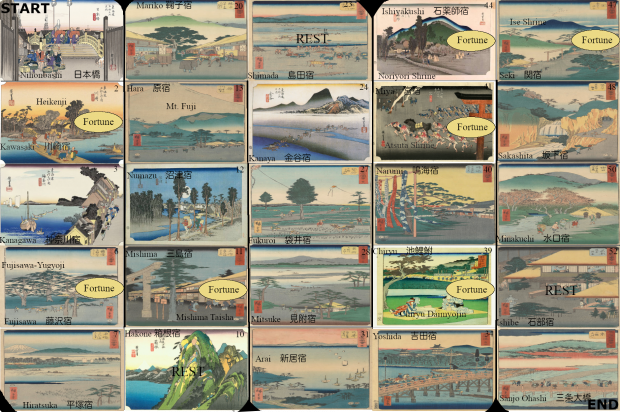

Assuming two players in the game (it can be played with more):

Each player throws the dice in turn and the one with the highest total moves the set number of spaces based on the dice and reads the associated short paragraph (each space is accompanied by an information card).

“Surprise” spaces require a detour or a return to the start. If one player lands on a “surprise” square they receive the lowest points for that round only. The information on the cards may also include images. Meanwhile, while one player reads the information provided, the other player must carry out “burpees” (a squat thrust with an additional stand between reps; an exercise used in strength training) until the other player is done reading. The burpee is intended to convey to the player that they are consuming energy during their travels.

By retracing Tsuneno’s steps I hope you can experience both the joys and tribulations of travel and imagine what it would have been like to be a woman making her way through the floating society of her time. This is not only a tale of travel, but also a journey of one woman’s growth. On the way to Edo, her path was unknowable and it could involve detours or reversals. For this reason, the game contains “surprise” spaces–just like her life, the game may be rough or smooth. The game also highlights gender issues, historical background, marriage issues, family issues, culture and nature disasters, and how these all intertwined leading up to her death. Tsuneno is a “product” of times. Finally, the main idea shared through this game and borrowed from the Stanley book is: “The crucial and irrevocable part of the story—was that she was moving forward. Her momentum carried her” (Stanley, 2020).

Bibliography

Stanley, A., & ProQuest (Firm). (2020). Stranger in the Shogun’s city: A Japanese Woman and Her World (First Scribner hardcover ed.). New York: Scribner.