Tianqi Chen

Game Commentary:

Filial piety, requiring respect, obedience, and care for one’s parents and elderly family members, was one of the most significant concepts of Confucian values, and a heavy influence on East Asia, including early modern Japan. The classic Confucian expectation of women’s filialness was raised in Liu Xiang’s Lienü Zhuan, emphasizing the highly idealized “exemplary woman” (lienü) as a model for behavior and comportment (Yonemoto, 2017). Within patriarchal Confucian society, the standard of the exemplary woman is based on her devotion to men, such as a husband, father, son, or teacher, and to family honor. Through sacrifices, women offer benefit to others, constituting one of their virtues (Yonemoto, 2017). In the Edo period, a woman’s filial piety was defined by serving her husband’s parents and bringing honor to her family through marriage. Ito Maki (1797–1862), was a commoner woman who was the eldest daughter of a prominent physician in Mimasaka Province. Her father, Kobayashi Reisuke, was a physician with a broad intellectual network and a student of Western science (Yonemoto, 2017). Maki received a good education and was able to express her filial piety and longing for her family of origin in her writing in later days. Maki’s family underwent various traumatic experiences, which profoundly influenced Maki’s life and created a filial bond of attachment between her and her parents. Maki was adopted by her childless uncle Kōzaemon, and she moved from Mimasaka to join her uncle’s family in Edo. Maki’s uncle Kōzaemon has higher social status than Maki’s father. He had acquired hatamoto status (Yonemoto, 2017).

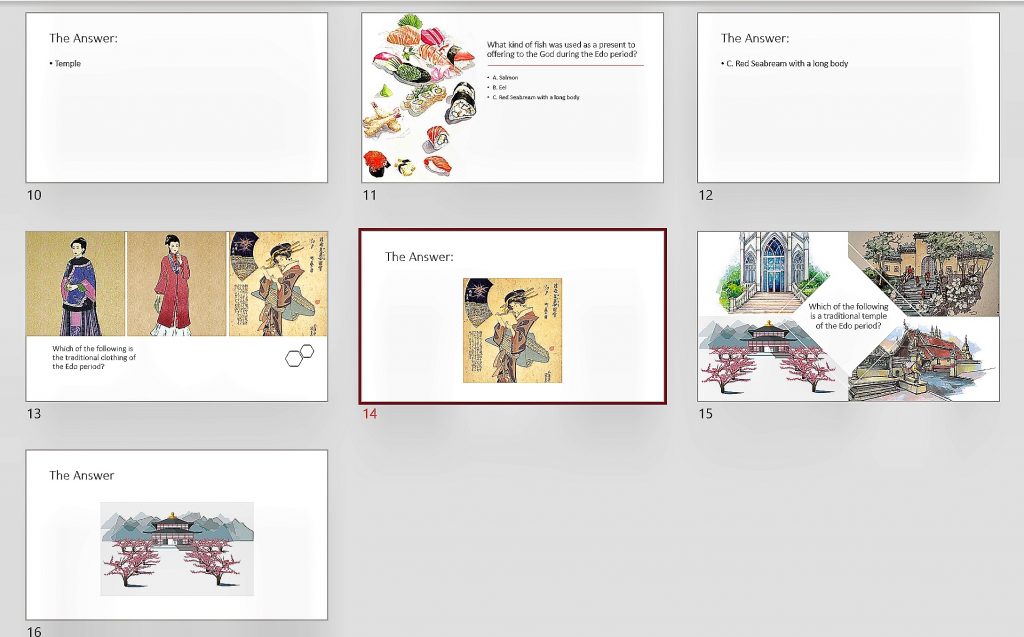

Because marriage in the Edo period was about equal social status, through adopted by her uncle, Maki could raise her social status and marry into a better family, fostering a good reputation for her natal family. Therefore, this journey from Maki’s hometown Mimasaka to join her uncle’s family in Edo became a life-changing choice that would define the rest of her life. Based on historical evidence, Maki chose to be adopted by her uncle and married into a better family, thus fulfilling her duty of leaving a good reputation for her natal family. However, Maki also paid the price. She was not allowed to contact her original family at all, even though she missed them dearly. Maki could only express her filial piety to her parents by writing letters, and she once mentioned that she felt delighted when she saw the map of her hometown. Unfortunately, Maki never returned to her hometown for the rest of her life. She noted in her letter a desire to fly back to her hometown like a bird. Although women had very few choices in the Edo period, there were still some choices that women could make to escape the fate of marriage, such as serving in a wealthier home. Therefore, this map game adapts Ito Maki’s real-life story by giving her a second option to serve in a household of rank and to raise her stature and that of her natal family through hard work. Two routes are given to her as two different options: go to Kyoto and work, or go to her uncle’s house at Edo. These two routes both travel via the Tōkaidō highway, the most essential and convenient route during the Edo period, following the fifty-three post stations (limited here to six critical post stations).

Game Instructions:

Material and Procedure:

- Two single six-sided dices

- The map board with the number of each station, and each station has two numbers

- The question cards

- There are two options for the player: one is to go to Kyoto and work, the

other to go to Maki’s uncle’s home in Edo–the player make the choice. - After the players make decisions and roll the two dice, the number of dices the players

throw determines the station where they land. - When the players arrive at the station, they must answer the common knowledge

questions about Edo Japan, and only when they give the correct answer can they move

on. - The players who arrives at their destination first is the winner.

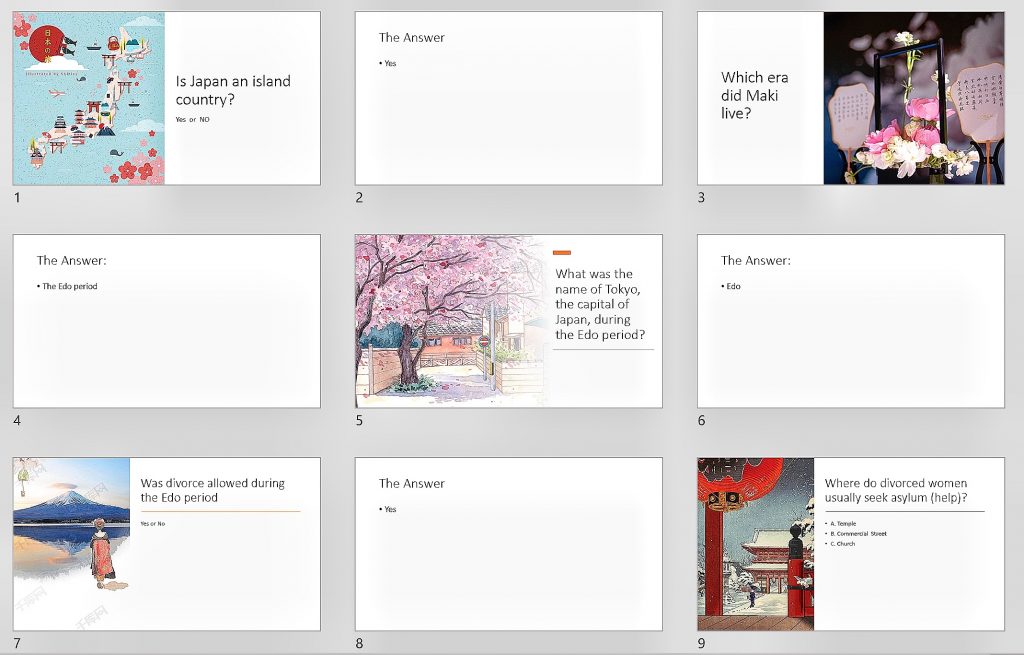

The question cards with answers:

Power point link to question cards:

https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/17BGoX9Zu06KoXmkvrkhSngXmKWHmRXkQ9

Vmq26ImVUw/edit#slide=id.p1

The Game Board:

The link of the dices:

https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1O5BAYfX4uRIYETumdkKtKCzHw84T_pR3Fu-3

O-fBiiw/edit#slide=id.gd3777506be_0_12