by Max Cameron and Fabiola Bazo

The Mark

April 14, 2011

The resurgence of the Fujimori family in this year’s elections threatens Peru’s development.

This past Sunday, Peruvian voters selected Ollanta Humala (under the banner of Gana Perú) and Keiko Fujimori (Fuerza 2011) to enter a second round of voting, or ballotage. Voters chose between 10 candidates for the presidency, and from 13 congressional slates. Definitive parliamentary results will not be known for days (or weeks), but it appears that Gana Perú and Fuerza 2011 will obtain the largest number of seats in Congress, followed by Alejandro Toledo’s Perú Posible. The runoff will be held on Sunday, June 5.

Humala was the only candidate to occupy the centre-left of the political spectrum. This is what got him into the top running in the last presidential election (2006). At that time, he lost in the runoff against a superior tactician, Peru’s current president, Alan García of the Alianza Popular Revolucionaria Americana (APRA). Under an amendment to Peru’s 1993 constitution, García was not allowed to run for re-election this time, and APRA did not even field a presidential candidate.

Unlike in 2006, when Humala aligned himself with Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez, in this election he has presented himself as a leader in the mould of the former moderate-leftist president of Brazil, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. By running a tighter, more professional campaign – one that cast him in a kinder, gentler light, as a caring father and husband and a moderate democratic leader – Humala significantly lowered the number of voters who viewed him negatively.

Humala’s success in the first round exposed the errors of politicians on the democratic right, many of whom believed that García’s victory in 2006 signalled the definitive triumph of moderation and market-friendly policies over populist nationalism. If Humala failed in 2006, they reasoned, his chances were even bleaker in 2011 after another five years of rapid economic growth. The assumption that the economic model was not at risk lulled the right into complacency.

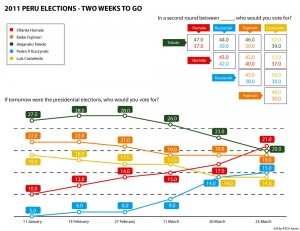

Discounting the need for unity, the right ran three candidates rather than one: Alejandro Toledo (Perú Posible), president from 2001-2006; Pedro Pablo Kuczynski (Alianza por el Gran Cambio), former prime minister and minister of finance in the Alejandro Toledo administration – which ran the country from 2001 to 2006; and Luis Castañeda Lossio (Solidaridad Nacional), former mayor of Lima. Try as many did, Peru’s right could not unite for this election.

Running against Humala is Keiko Fujimori, daughter of former Peruvian president Alberto Fujimori, who is currently serving a 25-year prison sentence for crimes against humanity. A victory by Keiko Fujimori would be a serious setback for Peru’s democracy. It would open the doors to the return to mafia rule and rampant corruption, to the abuse of power, and to the violation of basic constitutional precepts. It would also be a step toward the consolidation of a dynasty: Keiko Fujimori is not the only member of the Fujimori family to do well in this election. Alberto Fujimori’s youngest son, Kenyi Fujimori, who ran for Congress, appears to have obtained the largest number of votes in Lima, just as Keiko did in 2006. Many believe that, if she were elected, Keiko would immediately pardon her father. The joke is already circulating that Kenyi will run in 2021 so he can pardon Keiko, a clear allusion to the view that Keiko would end up in jail at the end of her mandate, as her father did, for human right abuses and corruption.