Fabiola Bazo and Maxwell A. Cameron

From FOCALPoint

When Peruvians gather at the polls on Sunday April 10, 2011, they will choose between 10 candidates for the presidency, and from 13 congressional slates fielding hundreds of candidates to fill 130 legislative seats. Their task will be complicated by the lack of a coherent party system and a large number of candidates. Most of the presidential aspirants are running with candidate-centred electoral vehicles. A second round seems unavoidable.

Photo: © Paolo Aguilar/epa/Corbis

Gana Peru party leader and presidential candidate Ollanta Humala greets supporters during a campaign rally in Lima, Peru, March 24, 2011.

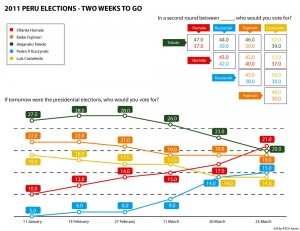

There has been remarkable volatility in Peru’s presidential race over the past three months. Outgoing President Alan García’s Alianza Popular Revolucionaria Americana (APRA) lost its presidential candidate Mercedes Araoz in January when she resigned over the composition of the congressional list. Now the once formidable APRA may be reduced to a rump in the legislature. In addition, the two late front-runners have failed to excite voters and have slipped in the polls. Luis Castañeda Lossio (Solidaridad Nacional), the former mayor of Lima who was considered a favourite a year ago, has been dogged by allegations of corruption. The exquisitely timed release of an audit of his administration in mid-March, combined with his poor performance in presidential debates, helped derail his generally ineffective campaign. Alejandro Toledo (Perú Posible), president from 2001-2006, had also quickly moved to the top of the pack, but faltered toward the end of the race. Keiko Fujimori (Fuerza 2011), a member of congress and the daughter of incarcerated ex-president Alberto Fujimori, has been another serious contender throughout the race, but she has had trouble expanding beyond her core base.

Two previously low-profile candidates have managed to pull up from behind with the decline of Toledo and Castañeda: Ollanta Humala and Pedro Pablo Kuczynski. At the end of March, Humala (Gana Perú) took the lead. In 2006, he won the first round of the general election only to be defeated by García in the runoff. This time he has moderated his image and distanced himself from Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez —an association that cost him dearly in that campaign.

Humala has walked a fine line between tapping into the frustrations of those left behind by a decade-long economic boom and trying not to frighten investors. He has worked with advisors from the Brazilian Workers’ Party to cast himself in the mold of successful leader Luis Inácio Lula da Silva. Humala has also benefited from the release of confidential cables from the U.S. Embassy in Lima by Wikileaks, which show how cravenly some of his opponents courted Washington’s help to cause his 2006 defeat. With the resignation of Manuel Rodríguez Cuadros (Fuerza Social) in early March, Humala is now the sole candidate to occupy the left of the political spectrum.

Kuczynski (Alianza por el Gran Cambio) has run on his record as former prime minister and minister of finance for the Toledo administration, competing with his ex-boss for credit as the architect of Peru’s current economic model. Kuczynski’s rise has probably contributed to Toledo’s decline. He has relied on a strong web presence, and met with TV celebrities to bolster his well-financed campaign. His good sense of humor when a woman grabbed him between the legs on the campaign trail has humanized him, especially among youth. However, the buzz around Kuczynski may not translate into votes; right-wing candidates in past elections have been limited in the number of votes they can attract beyond certain social groups.

The remaining five candidates, a collection of colourful characters, failed to collectively garner more than one per cent of voter intentions in most polls. With no candidate remotely close to the 50 per cent mark, a runoff seems unavoidable, though it remains hard to predict who will pass into the second round, as differences among candidates fall within the margin of error. The final stretch will be tense, and may hinge on effective campaigning for the substantial undecided vote.

Overall, without coherent parties this election has lacked distinctive programmatic alternatives, and campaigns have emphasized celebrity and spectacle. In part, this is because the candidates, with the exception of Humala, tend to agree on many issues.

However, Peru’s preferential congressional list system encourages this type of candidate-centred competition, with contenders competing against their peers on the same ticket as much as against rival parties. As a result, campaign spending and advertising often reaches a level of intensity that confuses and annoys voters.

The lack of party organization has resulted in a series of extensively publicized problems within internal primaries, and a lack of quality control in the nomination of candidates. Media reports of allegations regarding the sale of nominations and political donations from drug traffickers have contributed to public cynicism.

Notwithstanding the volatility of the electorate, there are a number of relative constants in Peruvian politics. Most voters are pragmatic centrists and have a penchant for turning the tables on the political establishment. The coast, especially Lima, carries a lot of electoral weight, and support in the south and central highlands, when combined with votes in the coast, can create a powerful bloc of voters.

Humala’s ideological stance has the potential to attract voters for the first round, especially since the right-wing vote is split among several candidates. The result of the runoff, however, will depend on how those who voted for losing candidates in the first round decide to vote in the second. This is a big problem for Fujimori, Humala and Kuczynski, who probably have reached their electoral base. Toledo, for his part, would have a good chance of winning if he can make it into the second round.

As is generally true in Peruvian electoral politics, the best bet is to assume volatility to the end.

Fabiola Bazo is an independent consultant and founder of the “Peru Election 2006” blog. Maxwell A. Cameron co-ordinates the Andean Democracy Research Network in the Centre for the Study of Democratic Institutions at the University of British Columbia. The authors are grateful to Steve Levitsky, Cynthia Sanborn and Ann Cameron for comments.