The following remarks were delivered in a panel discussion on Anti-Terror Bill, C-51, organized by the Institute for the Humanities, Simon Fraser University on 3/24/2015.

Video of the entire event is available here.

Bill C-51 threatens the foundation of our legal system. It weakens the rule of law and the separation of powers which underpins our democracy. It will make our political institutions not only less democratic, and less robust as guarantors of our rights and freedoms, but also weaker—less capable of responding the threats we face and less capable of mobilizing collective action toward desired ends.

Our political system is based on the rule of law. That means nobody is above the law, the actions of all must comply with the law, and no person should be the judge of his or her own cause. Whenever the rules are made, implemented, and enforced by the same person or group of people, we find ourselves in a situation that is the very definition of tyranny.

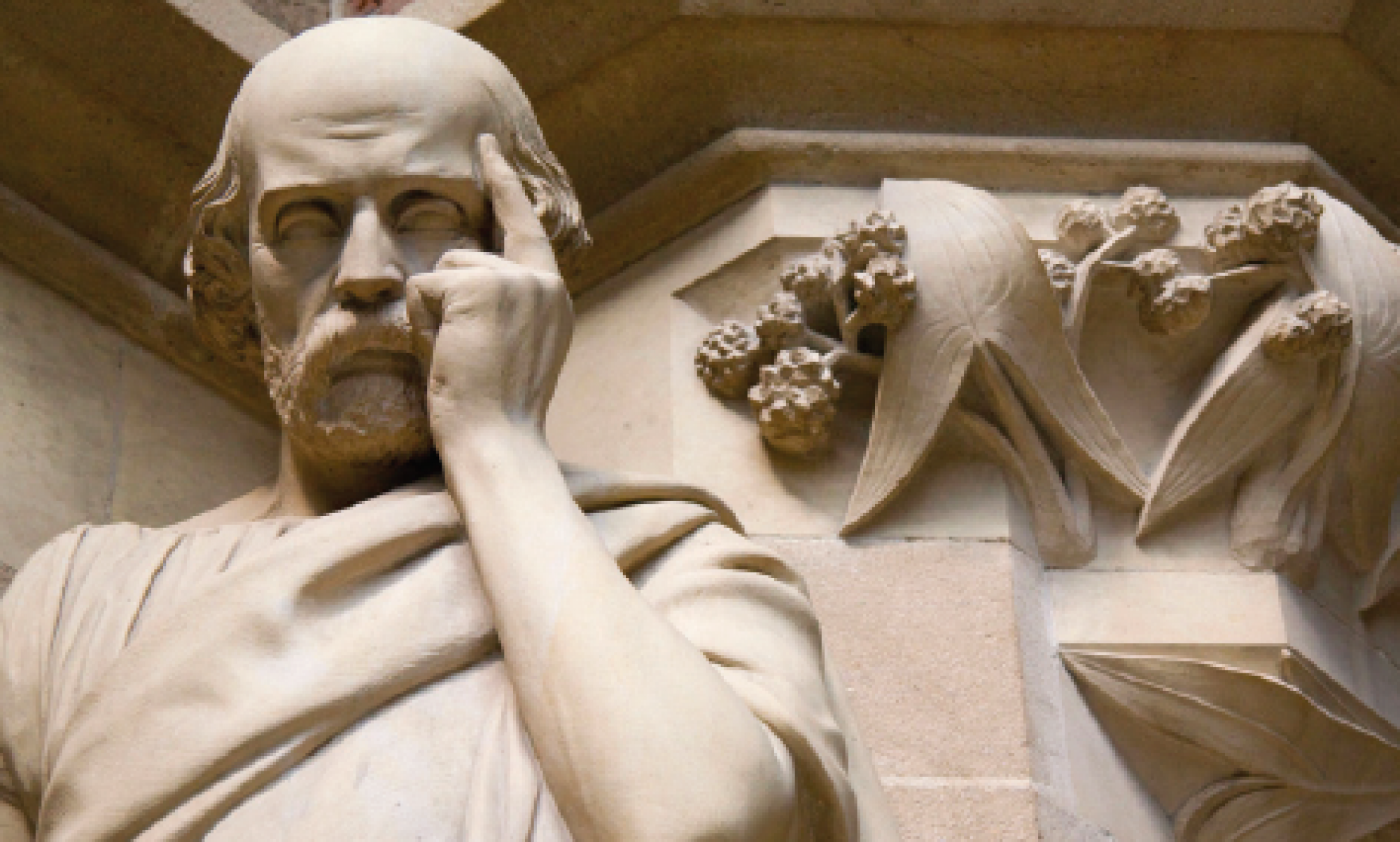

800 years ago the tyrant King John was forced to sign the Magna Carta, which affirmed “No free man shall be seized or imprisoned or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any other way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, expect by the lawful judgment of his equals or by the law of the land.”

Bill C-51 amends the Canadian Security Intelligence Act to allow CSIS to respond to threats to “the security of Canada” by means of measures that contravene rights and freedoms guaranteed in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. It also allows them to break Canadian law. That is, this is a law that explicitly authorizes law-breaking and violations of the Charter by our intelligence service.

What would the barons at Runnymede have thought of the idea of a judge-issued warrant to “enter any place or open or obtain access to any thing,” “remove or make copies or record any information, record or document,” or “install, maintain or remove any thing”? Such sweeping powers were precisely their target.

Such abrogation of the law or the constitution are to be given a fig leaf of legality, which only makes matters more obnoxious. Law-breaking is to be authorized by a warrant from a judge. Except that a judge may not authorize specific illegal activities that are explicitly exempted: CSIS shall not cause death or bodily harm, obstruct or pervert the course of justice, or “violate the sexual integrity of an individual.” What is wrong with this?

We cannot put a judge in a position of saying “the law says you must do X, but notwithstanding that you have my permission to do Y.” Permission on what basis? When a judge issues a warrant it is to guarantee—that is the origin of the word warrant—guarantee the legality of the actions of the police. It is not to find exceptions. It is not to exercise discretion with respect to what is the law. As Paul Ricoeur puts is: “The most fundamental limitation juridical argumentation meets has to do with the fact that the judge is not a legislator, that he applies the law, that is, that he incorporates into his arguments the law in effect.” It is the job of the judge, strictly, to say what is the law—neither more nor less. The very idea that a judge might counsel an illegal act is inimical to our rule of law tradition. It strikes at the very heart of our system of justice.

These provisions undermine the principle of the hierarchy of laws. This principle requires that when a higher law conflicts with a lower law, the higher law shall prevail. Constitutional guarantees cannot be trumped by statutory law; statutory laws cannot be abrogated by municipal ordinances; municipal ordinances cannot be negated by contracts between individuals.

Bill C-51 uses statutory law to interpret which guarantees contained in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms can or cannot be abrogated by a judge. It essentially creates two classes of constitutional guarantees—those which can be abrogated by a judge and those which cannot, and it does so in legislation that ranks below the constitution. Who gave the parliament of Canada the right to reinterpret our constitution and to decide that there are two tiers of guarantees?

To reinterpret the Charter through ordinary legislation makes nonsense of our entire legal system and our constitution. It makes nonsense of the separation of powers.

As Roach & Forcese have said: “For the first time, judges are being asked to bless in advance a violation of our Charter rights, in a secret hearing, not subject to appeal, and with only the government side represented.” The Canadian Bar Association says C-51 “brings the entire Charter into risk, and is unprecedented.” The BC Civil Liberties Association claims: “The role of the court in our constitutional system is to ensure that both the executive and the legislature act in accordance with the law. To ask the court to authorize constitutional violations is simply offensive to the rule of law…”

The separation of powers requires that legislatures legislate, judges judge, and executives execute policy. There is a purpose to organizing the powers of the state in this manner. It is because no law, no matter how carefully written, is unambiguous or free from multiple interpretations.

Take a term like “terrorism.” What does it mean? We could argue all night about the intrinsic meaning of the word, but the reality is that law demands that we take general rules and apply them to particular cases.

To get the best results, you don’t write sweeping legislation and then leave it up to administrative agencies to decide how to best implement the law. You need to build in checks and balances, not to hinder the functioning of government as a whole, but to guarantee its consistency by ensuring that actions by government officials are deliberate, implemented effectively, and enforced impartially.

And the best way to accomplish this is by creating branches of government that are specialized in distinctive activities and that work together to generate authoritative interpretations that guide collective action in accordance with the public interest.

The sad truth is that our parliament has been emasculated to such a degree that it is no longer a meaningful deliberative body. We have omnibus bills that are so complex and comprehensive that their effects can hardly be understood by the MPs who pass them. These bills are rushed through committees that no longer do meaningful work, passed without amendments, following closure to cut off debate.

Among the weaknesses of our parliamentary system is the lack of parliamentary oversight of the intelligence service. Such oversight is absolutely necessary to ensure that the implementation and enforcement of the law is compatible with the rule of law and the public interest.

Many people will object to Bill C-51 because they fear it will excessively enhance state power at the expense of the citizen. That is a real danger. My objection, however, is to the way that this Bill weakens our political institutions.

It will do this not only by making them vulnerable to the abuse of power and to the loss of legitimacy that this will entail.

It will also do so by making it harder to mobilize the resources in our society that enable effective collective action in response to threats. It will create confusion over what intelligence agencies can and cannot do, what constitutes legitimate dissent, the role of the courts, and deliberative quality of our legislative institutions.

Elements of Bill C-51, if passed, must be disobeyed. By whom? By our courts. I expect that this legislation will set up a major conflict between the executive and judicial branches of government. The courts must strike down this legislation as inimical to the Charter.

Canada cannot and should not mark the 800th anniversary of the Magna Carta by tossing key principles from it in the dust bin.