Have you ever been caught in the awkward position of guessing someone’s age? While there may be a number of you who think they’ve mastered the art of age approximation, we can assure you there are geologists out there who can put you to shame. While some people ballpark their mother-in-law’s age a decade below their real guess, geologists are much more skilled with their estimates, even when faced with dating a mountain back millions of years. In this blog post, we’ll be looking at the work led by UBC professor and researcher Dr. Joel Saylor, who dated the formation of mountain ranges in the Peruvian Andes (and these aren’t unfounded guesses, they’re measurements!).

Photo by Willian Justen de Vasconcellos on Unsplash

The research led by Dr. Saylor was primarily the work of his Ph.D. student Kurt Sundell, where together they trekked the stunning Andes mountains with the quest to find out more about its past. When asked about a personal highlight while researching in Peru, the response was a thoughtful pause followed by, “Wow… I mean there’s so many”. Along with the beautiful views that the Andes peaks provided, Dr. Saylor and his team had the opportunity to discover more about its elevation history.

A technique to look at the history of mountain formation

In order to date when and how quickly surface uplift (a dramatic increase in surface elevation) occurred in the Peruvian Central Andes, Dr. Saylor and his colleagues collected samples of hydrated volcanic glass and samples of stream water around the area. The volcanic glass preserved ancient water from millions of years ago, and the modern stream water provided the baseline for calibration. Amazingly, through a comparison of the isotopic components of these samples, the research team was able to find the elevation at which the volcanic glass had formed upon.

Hydrogen Isotopes

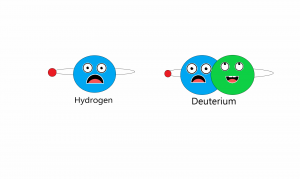

To understand how water molecules are in any way indicative of a rock sample’s elevation, we need to first understand that water is made of hydrogen and oxygen. However, water is not always made up of the same types of hydrogen and oxygen atoms. The hydrogen in water can be different isotopes (AKA different versions, varying in the number of neutrons). Regular hydrogen has one proton and has a mass number of 1, whereas deuterium (the other version of hydrogen) contains one proton, one neutron, and has a mass number of 2. Most water contains hydrogen-1, with deuterium being the less common isotope. Hydrogen-1, or protium, and deuterium are known as light and heavy hydrogen, respectively.

Hydrogen-1 and Deuterium. Image made by Monica Lee

We can measure the ratio of deuterium to hydrogen in water. When there is more deuterium than normal, the water is called heavy water. This is an important tool for geologists and climatologists because the presence of heavy water can tell us a lot about the elevation and climate of the area.

Dr. Saylor explained: “The fundamental reason for using deuterium instead of oxygen is that volcanic glass, which is our recorder for the past, doesn’t record oxygen… The volcanic glass incorporates into itself hydrogen but not oxygen.”

When rain clouds move from the lower elevation coastline to higher elevation mountains, they precipitate heavy water to light water. That is, in areas of lower elevation, water that has greater deuterium to hydrogen ratio is rained out compared to the water at higher elevations. Then, this hydrogen is used in the formation of hydrated volcanic glass. So, by finding the ratios of heavy to light hydrogen in their dated volcanic glass samples, they were able to date the elevation of the Andes into a timeline of the mountain range’s formation. For an easier-to-follow account of how deuterium-hydrogen ratios indicate elevation, have a look at the video below of Dr. Saylor explaining the concept.

Having dated the volcanic glass and measured the deuterium-hydrogen ratios of the hydrogen in the volcanic glass, Dr. Saylor and his colleagues were able to determine when the elevation change occurred and the rate at which it occurred. Through a comparison of his timeline of the Andes formation with changing conditions in the region, the team was also able to analyze the mountain range’s impact on its surrounding area. Their findings revealed that the uplift contributed to the beginning of arid or dry conditions to the east of the Central Andes, providing further evidence alongside other studies, that the presence of mountain ranges impacts the region’s climate.

Moving Forward

To sum it all up, the podcast below provides a basic summary of their research, as well as what we can take from it moving forward. Additionally, Dr. Saylor provides some insight into how paleoelevation work can cross over into other scientific disciplines.

We’d like to extend a special thanks to Dr. Joel Saylor, for providing us with material for the blog, video, and podcast.

Written by: Tim Chan, Tae woo Kim, Monica Lee, Sylvester Li, and Sandra Yoo

Nov. 27. 2019

About Dr. Joel Saylor

Dr. Joel Saylor is an assistant professor at the UBC Department of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences. Dr. Saylor was first introduced to the world of geology whilst taking a class with visiting professor Dr. Paul Taylor in the Himalayas. It was then that Dr. Saylor decided to leave the path of an engineer and become a geologist. During his Ph.D. research in Tibet, Dr. Saylor’s advisor pitched him the idea of studying the elevation history (also known as paleoaltimetry) of Tibet. Dr. Saylor has continued to study paleoaltimetry of locations around the world ever since.

——