(or How Urie Bronfenbrenner meets Arnold Sameroff)

Objectives: The next two models will show how looking at the developing child through a model system helps us gain awareness and new perspectives, organize our ideas, guide our practices, and evaluate intervention techniques

Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Model

Those who study children try to understand what factors influence their development within a system (Fig. 1) that includes the children’s families.

Two models that will be used in this course are Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model and Sameroff’s transactional model. Both view the child as existing within an intricate system of variables, all of which could have an effect on their development.

Figure 1 shows the solar system where the planets, stars and satellites are all connected, just like in a family system.

Urie Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model:

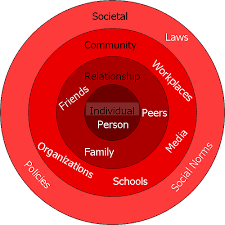

The ecological model (Fig. 1) outlines how the environment influences child development. It’s divided into a number of “systems” that describe different aspects of an environment. They are:

Fig. 1: The ecological model

Micro System: the child and what they bring to the world with them. This includes temperament and any conditions they may have.

Meso System: the immediate setting in which the child lives, such as the nuclear family.

Exo System: the environment in which the child lives. This includes the school the child attends, the community and neighborhood in which the child lives, and the occupation of the child’s parent.

Macro System: the general society in which the child lives. This includes the broader culture as well as the government and any regulations and policies it has, which may affect the developing child.

Chrono System (Fig.2): this includes any transitions in the child’s life that may impact their development.

Fig. 2: Chronosystem

Arnold Sameroff’s Transactional Model1

Arnold Sameroff proposed the “Transactional Model of Development”2 in the 1970’s. He believed that both nature and nurture are constantly being changed by their interaction with one another. This means, developmental outcomes are a function of neither the individual nor the context alone, but both (Fig 3.).

Fig. 3: This picture illustrates the transaction that happens between nature (plant) and nurture (person caring for plant)

The transactional model looks at development as a result of a complex interplay between the child and their natural personality and traits, as well as family experiences and economic, social and community resources.

The transactional models also look at “proximal influences” and “distal influences”. Proximal influences are the factors that influence the child closely. Interactions with the parent and family are examples for proximal influences. Distal influences are those affecting the child less directly, for example, the family income and the type of community. Infants and young children spend more time with their parents and caregivers; this is why they are more dependent on their “proximal influences.” Older children would tend to be more influenced from distal factors including their school and community.

At the same time, distal factors do impact parents/caregivers in ways that may affect their ability to provide for their child. Sometimes negative factors, such as family unemployment, may result on additional risks to the development of a child. Risks are not measured one by one, in terms of how negative the outcomes could be, but in their combined effect on a child’s development.

Sameroff uses the following terms to illustrate his model (Fig. 4):

Fig. 4: This image shows that certain genes (genotype) work together in the make-up of an insect (phenotype)

Genotype (see full Glossary) – related to the child’s genes; for example, eye colour or dimple on cheeks;

Phenotype (see full Glossary) – how the child looks; for example, child’s height and weight;

Environtype (see full Glossary) – related to child’s own family and culture (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5: This image shows a child behaving in different ways in two different environments