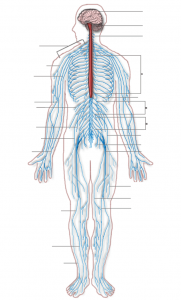

Children with Cerebral Palsy (see full Glossary) have a movement and posture control disorder resulting from damage to the brain anytime during pregnancy or between birth and age 3 years. CP does not result from conditions that affect nerves or muscles themselves1.

Cerebral Palsy may be caused by genetics disorder (see full Glossary) and other factors such as abnormal brain development or injury to the brain, including lack of oxygen during pregnancy or birth.

A baby’s brain can be injured by drug or alcohol exposure, lack of enough oxygen to the brain, maternal infections, infection in the infant or young child or head injury.

CP is a non-progressive disorder; that is, it does not get “worse.”

Description2

Children with CP have a range of movement disorders. These disorders are categorized depending on both the location on the body and the type of movement affected.

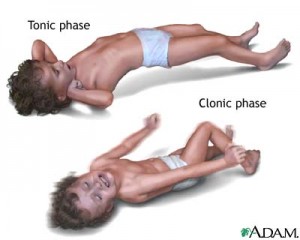

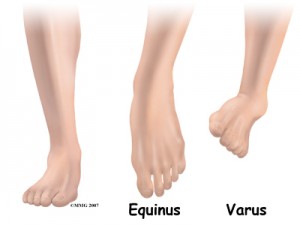

Cerebral Palsy may cause abnormal muscle tone, involuntary movements and/or lack of balance and or/coordination. This is why the description of CP includes the type of movements affected; e.g., ataxic, spastic, athethoid, or mixed CP.

Figure 1. Cerebral Palsy

For the spastic CP type (see full Glossary), depending on the location of the body that is affected, it is known as:

- Monoplegia (one limb, arm or leg)

- Diplegia (affects the legs, with spasticity and problems with balance and coordination );

- Hemiplegia(affects one arm and leg on the same side of the body);

- Paraplegia (lower limbs);

- Triplegia(affects three limbs; e.g., one arm and both legs; similar to quadriplegia, but with arms less affected);

- Quadriplegia (affects all four body limbs; it is often more severe than the other forms; sometimes with head and neck paralysis as well);

- Double Hemiplegia (this term is one that is less specific so the definition is also less consistent. It is often used to describe cerebral palsy that affects all four limbs so both arms and legs are weak, but with asymmetry (see full Glossary) between the right and left sides).

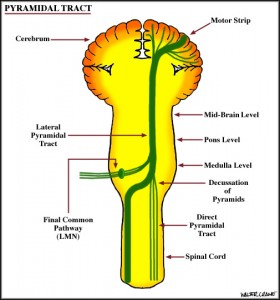

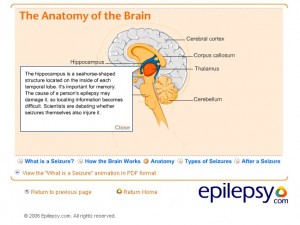

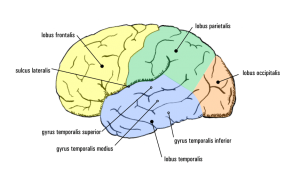

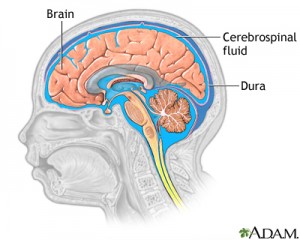

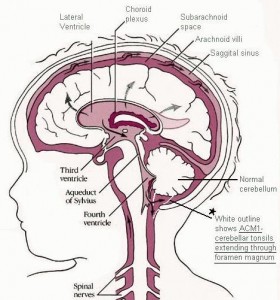

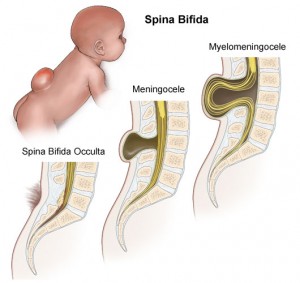

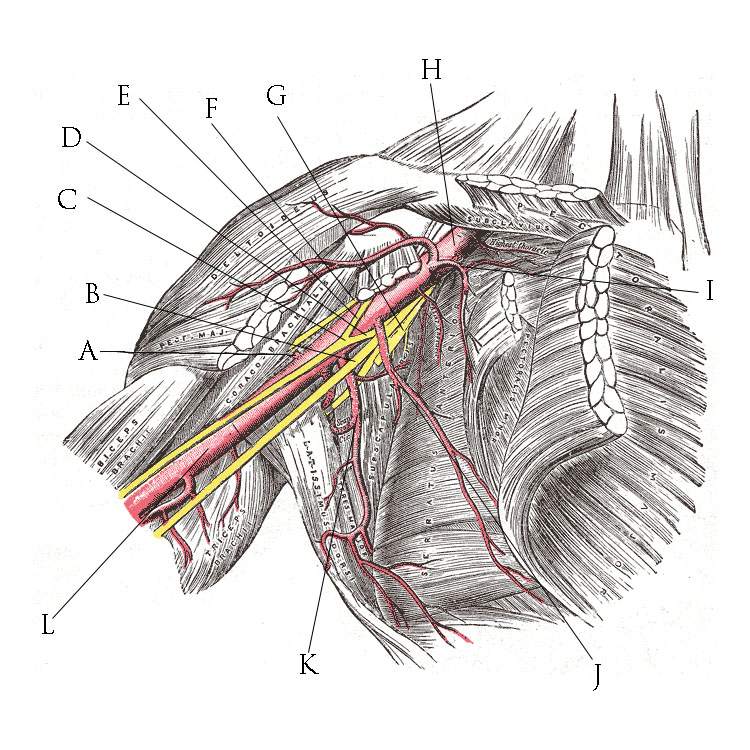

The description of CP also includes where the damage or injury comes from in the brain1; For example, CP may be pyramidal (Fig. 2), meaning the motor paths in the brain are damaged. Or it may be extra-pyramidal (Fig. 3), meaning areas in the brain that deal with motor function are damaged.

Figure 2. Pyramidal CP – The motor paths in the brain are damaged

Figure 3. Extra-pyramidal CP – Areas in the brain that deal with motor function are damaged

Intervention options

Intervention for children with CP usually requires the attention of different health, therapy and educational professionals. This is because, in addition to dealing with movement challenges, children with CP may also have other conditions, including vision and speech impairments. A large number of children with CP also have seizures.

- Physiotherapist (PT): May address hypotonia or hypertonia difficultiesby trying to lessen the effects as early as possible.

- Occupational Therapist (OT): May address quality of movements and how to use limbs affected by hypotonia or hypertonia ; in this way, effects are lessened and children are aware of how to utilize their working muscles.

- Speech and Language Pathologist (SLP): May address delays in the development of language and communication skills as a result of either motor and/or cognitive difficulties.

- Consultants in British Columbia’s early intervention and child development support programs, IDP and AIDP, and SCD and ASCD: Children birth to age 3 years may be referred to IDP/AIDP. Children 3 to 12 years, and who have a special needs or medical designation that requires special support, and who attend a center based program, may also be referred to SCD/ASCD.

- Mental health specialist: May assist with any mental health difficulties a child with CP may experience.

- Vision and hearing specialists: Vision and hearing should be checked on a regular basis.

- Academic preparation-Learning Assistance teacher: Some children with CP experience cognitive and language delays. Getting them ready for school could be beneficial.

Assistive technologies: Some assistive technologies may be used to help to develop cognitive, social, academic and communication skills.

To learn about cerebral palsy in the middle childhood years, please visit the six to 12 part of this course.

1. Cerebral Palsy — The Dana Guide By Alexander H. Hoon, Jr. and Michael V. Johnston, March 2007.

2. Origins of Cerebral Palsy at http://www.originsofcerebralpalsy.com/