3.2 maps.

In the opening of Marlene Goldman’s article “Mapping and Dreaming; Native Resistance in Green Grass Running Water”, she explains how Hugh Brody’s experience “testifies to the fact that Native American peoples have repeatedly asserted the legitimacy of their own maps and contested European maps and strategies of mapping, which have played such a central role in conceptualizing, codifying and regulating the vision of the settler-invader society” (17, emphasis mine). This can be seen in the very maps we use today, where Africa and South America are much smaller in terms of relativity to how big they actually are. Here’s a fun, yet informational video about the traditional maps we use today:

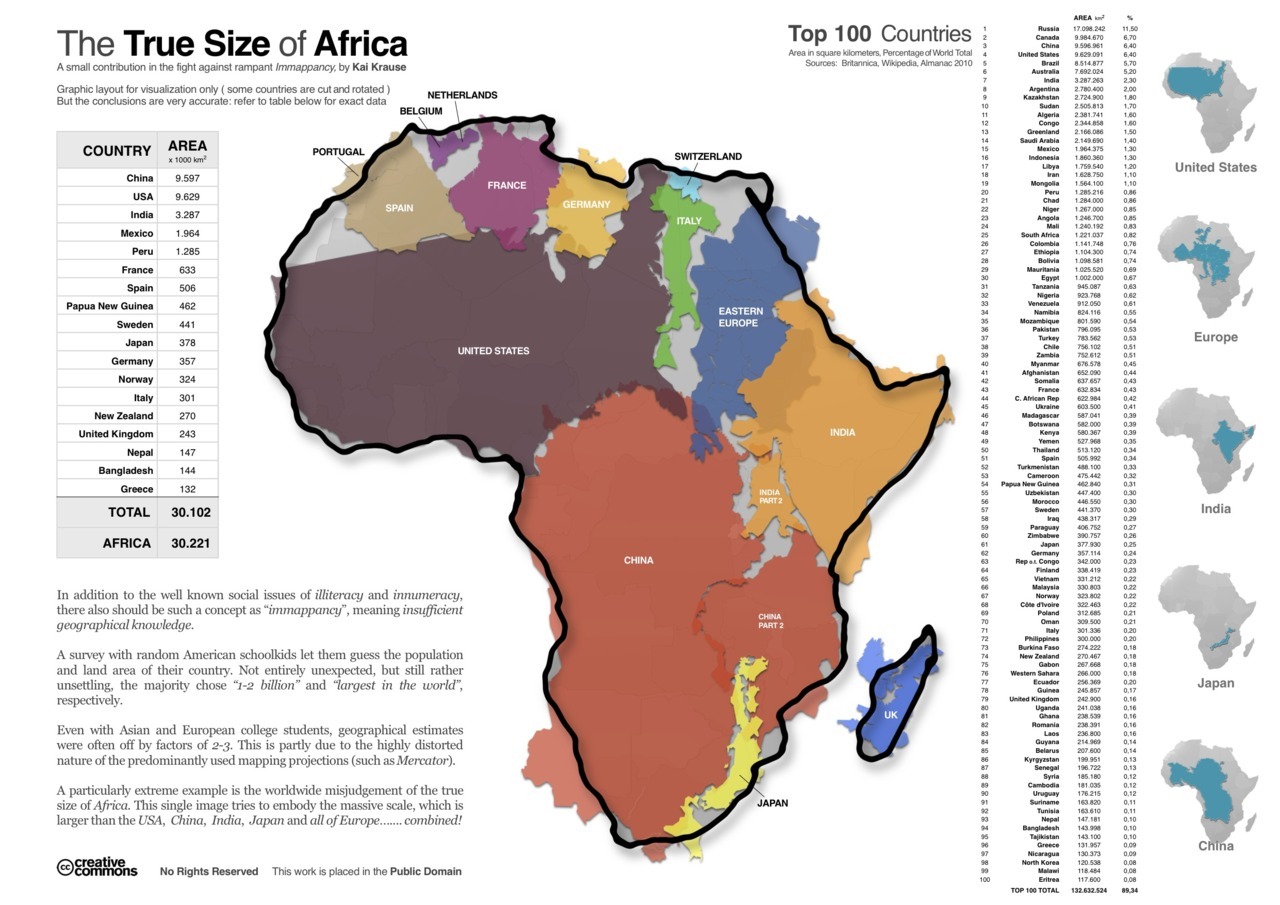

Africa is fourteen! times bigger than Greenland, and yet on the traditional map they appear to be the same size. According to this infographic, 18 countries fit into Africa and yet Africa is still bigger!  Something as basic as a map can greatly reinforce these social systems of European superiority and regulate the European vision of settler-invader society. Just as Africa is diminished in size, importance and cultural integrity, we see how conflicts in mapping and charting has historically diminished the size, importance and cultural integrity of Native Americans. These conflicts have displayed differences between Native American and European ideologies, which are played out in Thomas King’s Green Grass Running Water. He uses mapping and charts as a metaphor to present both European (linear) ideologies, as well as Native American (circular).

Something as basic as a map can greatly reinforce these social systems of European superiority and regulate the European vision of settler-invader society. Just as Africa is diminished in size, importance and cultural integrity, we see how conflicts in mapping and charting has historically diminished the size, importance and cultural integrity of Native Americans. These conflicts have displayed differences between Native American and European ideologies, which are played out in Thomas King’s Green Grass Running Water. He uses mapping and charts as a metaphor to present both European (linear) ideologies, as well as Native American (circular).

To me, at the center of King’s mapping metaphor is the idea of subjectivity. In a broad sense, this concrete idea of a map is highly subjective. Cartographers are drawn to difference aspects of a landscape and so their maps reflect that subjectivity. In terms of stories and orality, story telling is also subjective. Based on who we are in the moment of hearing or telling, we are drawn to different aspects of the story, and though the overall structure of the story may remain, the emphasis and content of the story itself might change based on our own subjectivity. The Native American circular way of charting and mapping reinforces this subjective idea more than the European linear/rational way. As discussed in earlier lessons, the European way of thinking reinforces dichotomies and erases possibilities for subjectivity and multiple perspectives.

I found this recent post/story by NPR, where a 34 year old mixed-Cherokee Indian (I say Indian because that’s how he chooses to identify himself according to the story) has spent years researching and creating maps of North America with over 600 tribes and their original names.

Here’s a picture of the map: http://www.npr.org/assets/news/2014/06/Tribal_Nations_Map_NA.pdf

What’s interesting to note is that today’s modern land divisions are not even remotely applicable to the Indian’s tribes.

I’ll leave you with a few memorable quotes from the story:

“This is Indian Country, and it’s not the Indian Country that I thought it was because all these names are different.” Doug Herman

“Naming is an exercise in power. Whether you’re naming places or naming peoples, you are therefore asserting a power of sort of establishing what is reality and what is not” Doug Herman

“But it’s [his mapmaking] a way to convey the truth in a different way” Aaron Carpella

^ More than anything, this reinforces that mapping and charting is ultimately subjective. There is no singular truth; the truth itself is our own perception.

Works Cited

Goldman, Marlene. “Mapping and Dreaming; Native REsistance in Green Grass Running Water.” Canadian Literature 161-162 (1999). Web. 10 July 2014.

Lo Wang, Hansi. “The Map of Native American Tribes You’ve Never Seen Before.” NPR. Web. 10 July 2014.

“West Wing-Why Are we Changing Maps?” Youtube. Youtube.com Web. 10 July 2014.

“The True Size of Africa.” Americawakiewakie.com Web. 10 July 2014.

wow. great post. I love that you comment on mapping and naming as being ways to assert power. I’m immediately reminded of the novel (and film) The English Patient by Michael Ondaatje. In it, Ondaatje uses Egypt during the second war as a setting, and shows how ridiculous it is to see western civilizations coming in to fight for dominion over the land, and then trying to map it. The true absurdity lies in the nature of the land: sand. The landscape is a constantly changing landscape, that can be completely altered over the course of a few hours. For one to then try to draw lines on an ever-changing landscape is impossible.

What you do is state that mapping and charting are ultimately subjective. This is great. It would only take one question to both China and Tibet to prove that statement as correct.

Thanks for sharing! The video was great, really demonstrated the attitudes we often have about “the way things should be.” Also, thanks for including that beautiful map of North America with the original names of the different tribes. In a way, it’s difficult to see a map like this without projecting mown geographic perceptions of where cities and provincial borders belong. I think that without the provincial and state borders shown on the map, the map would look very strange to me, even uncomfortable, much like how the lady in the video felt when shown the new, more accurate map of the world. I’m amazed by the power of mapping to shape our perceptions of the world around us!

Hi Fidelia,

I really enjoyed your blog. I can’t believe how subjective maps are. My mind if officially blown. Reading your post, the desire/need for borders/lines drawn in the sand, interests me immensely. Like Lian mentioned, I too ‘think that without the provincial and state borders shown on the map, the map would look very strange to me.” But taking a closer look at the Indigenous map you posted that shows the many tribes that lived all over North America, I am struck by how liberating it would be to live without the borders of our degree. With that said, I can’t help but think of all the problems that those “lines in the sand” have caused all of us; how people are kept out of certain countries or even not allowed to leave others. Likewise, it’s scary because even land around the North Pole is now being fought over (http://metronews.ca/news/world/980914/the-far-north-turf-war-who-really-rules-the-arctic/). With global warming, it is becoming increasingly evident that soon oil and natural gasses will be able to be extracted from the North Pole and I have heard people mention that it will be World War Three (http://youtu.be/LtMF0lvolbM). After all, “13 per cent [(15% according to the video)] of the world’s undiscovered oil and a third of its untapped natural gas lies in the Arctic, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.” Which begs the question, will land disputes ever end? It seems like lines will keep being drawn right until the day that there is nothing left. It’s a scary thought, but it’s quickly turning into a reality.

What an interesting discussion! Like Lara, my mind is totally blown… haha!! I cannot believe that something I have taken for granted as being an indisputable truth, is actually so subjective. The clip from “The West Wing,” when the world map is shown upside really illustrated this point for me, because I realized “why not?”, it is equally as accurate as the way we have been viewing the world. I did a bit of my own research about this and learned something quite obvious (which again, I hadn’t really considered), that an accurate map of the world is impossible because the world is spherical and putting it on a flat surface automatically distorts it (http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/apr/02/google-maps-gets-africa-wrong).

With this in mind, my question for you is, how do we remedy this situation? Is there a better way to map the world? For example, is flipping the map upside down at great solution or too drastic?

Thank you!

Hi Fidelia,

I was just browsing through lessons and found yours so fascinating. The extent to which Eurocentrism dictates so many ordinary parts of our lives and education system truly is tremendous. Your example of the maps really captures it well and like other classmates said, it really is mind-blowing how far fetched the proportions of certain countries and continents are. I did some digging and found out that the western map we are commonly exposed to is the result of a distorted map created in 1596 to help sailors navigate their journey’s- For me, this is shocking considering that modern cartographers know this great inaccuracy and yet there is so little public knowledge to share the information. Also kin of interesting, North America looks as large as Africa and Greenland on this traditional map, however in reality the size of North America fits into Africa and STILL leaves room for India, Argentina and Tunisia. Crazy! ( check out this article for more: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-2596783/Why-world-map-youre-looking-WRONG-Africa-China-Mexico-distorted-despite-access-accurate-satellite-data.html) Of course, in the process of transcribing an image of the globe, proportions are bound to be a bit distorted, but I can’t help but wonder how much influence Eurocentrism must have had in projecting the ‘new world’ as a massive, powerful feature of the globe.

By the way, If you are interested in this topic, I encourage you to check out “The Challenge of Eurocentrism: Global Perspectives, Policy, and Prospects” by Rajani Kannepalli Kanth. I read it for one of my IR requirements and really provides some shocking insight on various European and American crafted stories that serve to promote Western civilization over all others, including Indigenous cultures.

Sorry for the ramble, and thanks for such an insightful post!