GIS and Crime – March 18th

This lecture covers how crime, space, and GIS can be related as criminal activity is assumed as non-random phenomena. Crime analysis overall can be qualitative or quantitative and generally analyzes crime data or any law enforcement agency’s response to crime, which ultimately contributes to reducing crime overall. There are three main environmental criminology theories that have underlying geographic assumptions. Routine activity theory applies a network of nodes where criminal victimization is likely to happen and utilizes socio-demographic features of environments to theorize the chances of criminal activity. Network analysis is also used to study organized crime. Next, rationale choice theory examines how the spaces most familiar to criminals are more likely to be spaces where criminal activity occurs. Finally, criminal pattern theory uses past data to explore possible patterns and create predictive models for future occurrences. GIS has become used widely by law enforcement agencies in municipalities to better understand potential threats and spacial patterns of crime.

GIS and Health Geography – February 29th

Today we discussed how we can apply GIS in the field of health geography. Health data can be extremely sensitive, uncertainties are always a factor, and it is difficult to incorporate good practices to form solid research. Using a well defined population group, using surveyed data, allowing for latency times and population movements are some good practices that make up a well considered study. Some studies approach issue by mapping the actual disease and others may focus on mapping disease determinants. GIS can effectively look at accessibility, exposure, social networks and capital that permit accessibility, and even physical activity opportunities. Often times GIS analyses are measuring the proximity of populations to health care facilities or potential health risks. I also learned that cluster analyses in health geography research commonly employ the Poisson distribution.

What is Health Geography – February 12th

Relating place and health

In today’s lecture we discussed what health geography is and the types of problems that are explored in the field. Health care geography is generally concerned with disease ecology, health care delivery, and how the environment impacts human health. Brian mentioned an emerging trend of wellness geography research that studies where people are well and healthy in the world. Health has always been intimately related to geography and I learned fluoride is actually in toothpaste because of work related to health geography.

There are many approaches you can take in health geography. All carry assumptions about society and what is deemed natural. For example, a humanistic approach would emphasize qualitative research and see illness as socially constructed with one’s perception of health as a major determinant of health. There are also cultural, structural, and spatial approaches to the strands that make up health geography research.

In the history of health geography, medical geography was initially the norm and research was led by physicians, which tended to have a heavy colonial influence. Brian explained that because GIS depends so much on quantitative data that geographers and social theorists remained very critical of GIS research. So there has been a shift in health geography from having traditional perspectives of disease and health as naturally occurring to a more nuanced perspective that relates human health to power relations. Brian noted that the BC government failed to acknowledge Lyme disease because ticks weren’t supposed to cross borders.

Landscape Ecology – January 29th

The presence of a water body in the desert allows for trees to grow nearby. Landscape Ecology!

In lecture we discussed how to approach landscape ecology and the key considerations used to study it. First, landscape ecology is all about the reciprocal interactions between the form of the landscape and the ecological processes occurring within the landscape. Ecological problems and processes are non-random because there is natural spatial autocorrelation happening because of the way landscapes or shaped. We discussed 1st order effects in landscape ecology, which occur when the underlying features of the land are creating the variability in observations from place to place. 2nd order effects also occur when the interactions between ecological forces form the land. Features and processes in landscape ecology can also exhibit stationarity if there is no differences over space (first order) or no interaction between objects or events (second order). The major types of processes that occur in landscape ecology can be summarized as abiotic, biotic, anthropogenic, and natural disturbances.

We ended this lecture with a brief mention of Brian’s work on fractals in landscape ecology. He mentioned there are many ways to explore the complexity and heterogeneity of a landscape, and that is what we will be doing in the first lab.

Geography is Important, but why? – January 22nd

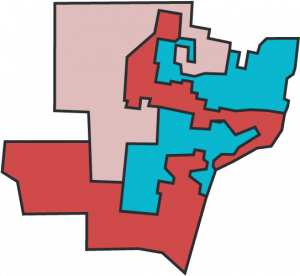

Gerrymandering (Clipart)

In today’s lecture we discussed three salient issues that have come about through spatial analyses. First we have the ecological fallacy, which occurs when we attribute characteristics of an environment based on some aggregated data to an individual. Next, we went over the Modifiable Arial Unit Problem which arises when we represent data at different scales or zones and end up with different statistical results. The MAUP should always be considered when we represent data and a fair way to recognize it is by representing the data at different scales to show how the MAU effect could be affecting the data. The MAUP arises in U.S. politics with the issue of Gerrymandering and is in part why Republicans hold so many seats in the House of Representatives in states like North Carolina. Finally we have the Simpson’s paradox, which can be observed when we agglomerate local data and ultimately show a broader trend that conflicts with the trends of data in local scales.

We discussed these issues in the context of the decisions that go into deciding the extent and scale of study areas. Edge effects can potentially change conclusions in a study, because often times data collected in the field is interpolated in space using Kriging methods.

Introduction to Course – January 8th

Today, we discussed the different applications of GIS and reviewed the three major topics that will be reviewed in this course, which will be Health Geography, Crime and Landscape Ecology. Brian reminded us that GIS is often used in these fields to identify potential spatial patterns, such as hot spots and clusters. GIS effectively attempts to model the interactions occurring within an environment. In Landscape Ecology we will be looking at how the landscape affects and reacts with abiotic and biotic processes. In Health Geography there are three major facets where GIS application is especially useful; disease ecology, health care delivery, and the environment and health. Using GIS we can model things like the spread of infectious disease, the accessibility of health care facilities in a region, or the potential geography of pollutants in an environment, and all of these applications are related to Health Geography. Finally, we will also explore how GIS can be used in Crime analysis. Specific crimes can present spatial patterns and crime is always related to environmental factors such as population density and geographies of opportunity.

Think spatially!