In his chapter on chapter “Paper and the Printing Press” in Empire and Communication, Innis (1950) analyses the impact of print upon the world across approximately 500 years. With particular emphasis on Europe and North America, Innis probes the relationship between printing technology and the socio-political and economic developments that he saw as highly influenced by the speed up of communication afforded by technological innovation and the sudden expansion in the availability of printed material (particularly printed material on secular topics). Innis appraises this relationship with the eyes of a political-economist and repeatedly draws attention in his continental and trans-Atlantic tour, to the cultural disruptions that he saw as driven in large part by the force of technological change.

The scale of the change is truly extraordinary, especially if one just considers the main product of the increasing numbers of printing presses: pages, Bibles, secular tracts, political pamphlets, plays, poems, books, newspapers. Both the number of printed materials and the speed of their printing saw dramatic increases. For instance, Innis talks about the printing press blazing away at the speed of 20 to 200 leaves per hour in 1538 in France. Approximately 150 years later, in 1701, Innis refers to the development of the first daily sheet, the precursor to the modern newspaper. The technology now supported the production of 250 sheets an hour, or 2000 sheets in an 8 hour shift, a long shift for the printers who still worked the presses by hand. With the introduction of steam power in the Industrial Revolution, the rate of production increased dramatically. Between 1814 and 1853, according to Innis, the “production of newspapers was increased from 250 to 1000 copies an hour, then to 12000 copies an hour” (160). This increase in speed especially favoured the formation of print monopolies like that of The Times in London. Innis mentions a further jump in speed in the United States a mere 30 years later. “The cylinder press, the sterotype, the web press, and the linotype brought increases from 2,400 copies of 12 pages each per hour to 48,000 copies of 8 pages per hour in 1887, and to 96,000 copies of 8 pages per hour in 1983” (161). Therefore, in the 350 odd years that Innis sweeps through during the early development of this technology, the printing press accelerates the rate of information production from approximately 200 pages an hour to approximately 768,000 pages an hour. In this wake, the modern world is born and whole societies are transformed.

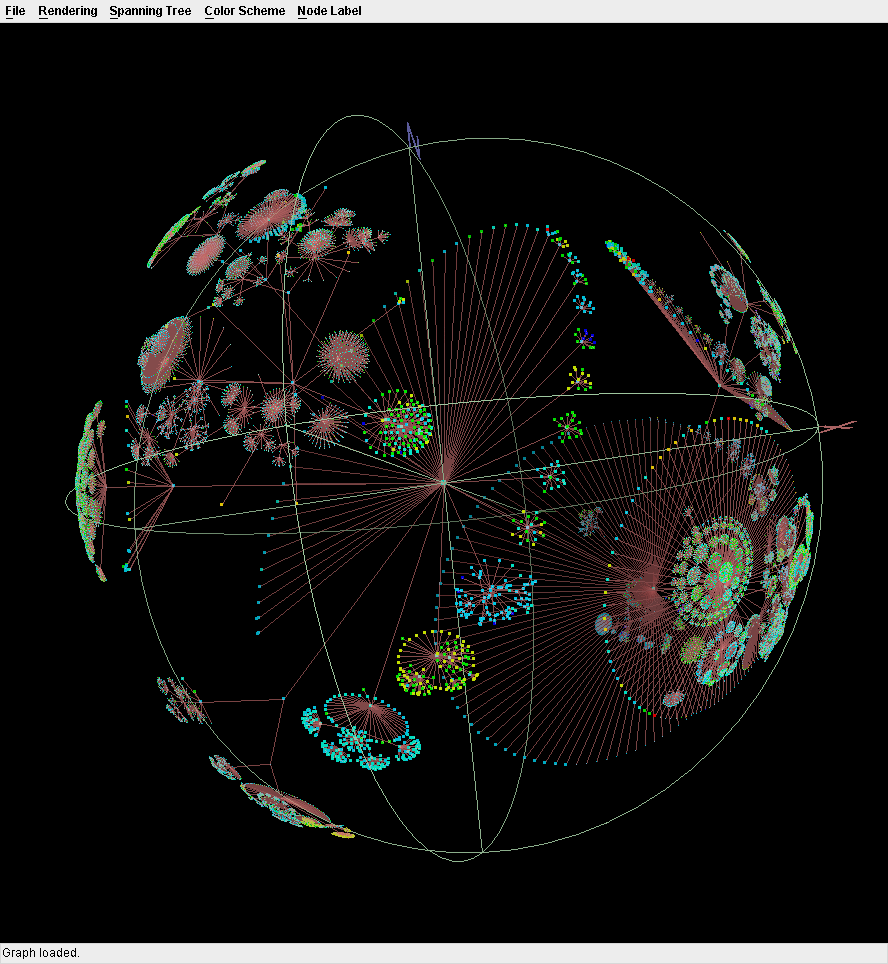

It is interesting to consider Innis’s points concerning the impact of the speed of communications in relation to what we see today with the development of the Internet. In 1994, the World Wide Web, a medium contained within the communications network of the Internet, was emerging as a powerful new way to exchange information across a distributed network of connected machines, dubbed the “Information Superhighway”. Marc Andreesen started an exciting new company called Netscape, and introduced a way to access pages that combine text and graphics. At this point, in Canada most people were connecting to the Internet using 28kbps or slower modems, so it was only practical to exchange text or simple graphical information. In 2004, data traffic on the Internet was estimated to be in the range of .006 Terabytes per second. Video conferencing was possible, but still only practical between specialized facilities and dedicated networks using high-speed network or satellite connections. This was, of course a very expensive and complicated way to connect people. Educators were very excited about the amazing opportunities afforded by the almost limitless expanse of 640 MB on a CDROM. Such amazing multimedia CDROMS were possible because of the power of the latest computer: a Pentium processor running at 90 Mhz with 16 MB RAM, 4 MB of Video RAM and a 500 MB Hard drive, running Windows 3.11. A powerful desktop computer like this cost in the range of $2000 US.

In 2004, the World Wide Web, or the Web, as it was then called, reached into almost every area of human communication. People connected to it using everything from desktop computers, to small personal digital assistants to cellular phones to, even, refrigerators! Broadband connections now extended into homes in many parts of the world, with penetration of high-speed connections with Cable, DSL and Optical lines reaching over 50% in places like South Korea, Sweden, and Canada. The rate of data was now over 30 terabytes a second. Good quality point-to-point video conferencing from desktop computers was now within reach of anyone through high-speed connections (for video and audio) and even 56k for audio-conferencing. And while CD-ROMs were still being produced by textbook publishers to support multimedia delivery of learning resources, people were now excited by the possibilities of DVDs and 4-8 gigabytes of storage. High-speed computers could easily handle these multimedia and networking challenges: $2000 US would buy you a 3.4 Ghz Pentium 4 processor, with 512 MB RAM, 250 GB of storage, a DVD burner, running Windows XP.

In 2009, the Web is now ubiquitous and reaches into most other media, creating a curious convergence of other media formats within its own network. Almost any media, from television, to radio, to movies can be found within the Internet (or are actually broadcast via the Internet, and this reality is having a dramatic impact on the knowledge monopolies of dominant sectors of society. The usage of the Internet in countries like Canada now is approaching 84% of the population. The rate of growth in data seems to be somewhere in the range of 100% per year, with Internet traffic in the range of 160 terabytes per second. Point-to-point and multi-point video conferencing is now readily available with consumer grade computers (and some cell phones). With optical media, music CDs are dying and a new format, BlueRay, is trying to usurp DVDs with the promise of 50 Gigabytes of storage. The future of physical optical media, however, is being challenged already by the increase in streaming media both at standard and high-definitions. The latest computers are no longer simply chasing after greater speeds or storage limits, and increasing numbers of users are choosing portability over speed. Netbooks (small, low-powered notebooks that take advantage of network based media and software) and cloud computing platforms (where applications are based on the network rather than on a local computer) now allow for computers well below a thousand dollars, not to mention phones or music players that are, essentially networked computers.

Innis would certainly marvel at the rates of change that recent telecommunications and computer technologies have achieved, though he would likely have little trouble in extending and refining the tools that he honed in examining the development of Gutenberg technologies into the 21st Century.