Question 3: Words

In his inspiring book If This Is Your Land, Where Are Your Stories? Finding Common Ground, J. Edward Chamberlin grapples with the universal practice and ceremony of storytelling, and seeks to “find common ground” between cultures as a way of breaking down and complicating our understanding of “Them and Us” in order to establish universal acceptance and respect for all peoples across culture, language, and tradition (8).

Chamberlin spends a great deal of time dissecting the use of words and language, recognising that humans have a tendency to draw a dividing line between “Us and Them,” between savagery and civility, between culture and anarchy, based on use of language. Language is often the dividing line between peoples, and when we are unable to understand another’s language, customs, and practices,they begin to seem more like “babblers and doodlers” than respectable human beings. “The categories of the barbaric and the civilised first take place along the lines of language with the dismissal of a different language as either barbaric or so basic that it could not possibly accommodate civilized thoughts and feelings,” and this conception of barbarism lends credence to the idea that those who speak differently are inferior (Chamberlin 13). If we characterise the ‘other’ as subhuman, incapable of ‘usefulness’ or productivity (as we understand it), and ill-suited to governance of themselves or of land, it becomes very easy to justify their subjugation. This is especially the case when they inhabit or possess things that we ourselves desire – land, for instance, or natural resources like gold or lumber. Greed or desire for resources skews perception in such a way that it is easier for us to think of the other as barbaric, and to justify the theft of homelands.

Chamberlin turns to story to help complicate this dualistic understanding of Us and Them. Communities from around the world all have in common the fact that they tell stories. The tales themselves differ, of course, but the ceremony of storytelling and the practice of believing in metaphor is universal. The very heart of language, as Chamberlin argues, relies on us learning to be comfortable with the paradox of believing and not believing at the same time. When we teach children to read, we teach them to recognise that “C-A-T” is at once a cat and also not a cat. Children take very easily to the world of metaphor and symbolism, they learn very quickly to believe and not believe at the same time, and this liminal space of acceptance/dismissal is essential for understanding stories as well.

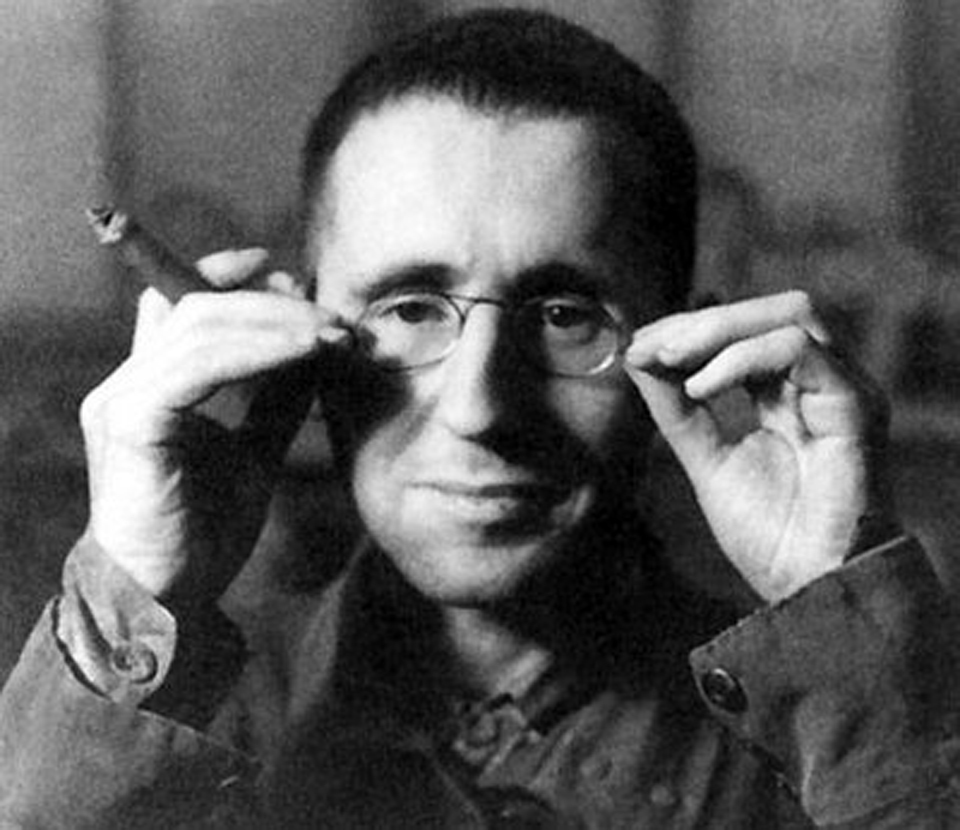

Chamberlin writes that “often it is when we are most conscious of their artifice that we surrender most completely to stories,” and this makes me think of the work of the German playwright and theorist Bertolt Brecht, who wrote a great deal about the dangers of believing too completely in the realism of the story presented on stage. To combat this, he created what he called Verfremdungseffekt, also known as the “V-Effect” or the “Alienation Effect”. He would intentionally disrupt the suspension of disbelief that traditional theatrical conventions require by doing things like exposing the back wall of the theatre, adding musical elements that clashed with the events on stage, and informing the audience of the plot in advance. He hoped that this would prevent them from becoming swept up in the emotional journey of the story and that they would be more able to consider the political implications of the piece. It’s a balancing act between making the audience care enough to think deeply about the issues, but distancing them just enough that they avoid leaving the story behind in the world of imagination without considering its political implications. Ultimately, Brecht was playing with the audience’s understanding of realism and artificiality, putting pressure on dis/belief.

Cultures around the world draw on the ideas of riddles and charms to teach lessons, tell stories, entertain, enchant, and instruct. Chamberlin understands riddles and charms as devices that drive a wedge between reality and imagination. They create a situation that requires the disintegration of language itself, or of our conception of the way the world works. Under the pressure of understanding charms and riddles, either we must radically rewire our understanding of the world, or our sense of language itself must dissolve.

In the case of riddles, “it is the language that gives” under this pressure: our understanding of the way language works cannot exist alongside the rules of the world, so the trick and the delight of the riddle is in showing us the artifice of words and metaphor, and, indeed, it is language that solves the problem in the end (Chamberlin 161).

It works the other way with charms. Ceremonies, national anthems, well-known prayers, and creation stories all manage to work some magic on our experience of the world. The logic of language is pitted against that of the world, and “in a charm, it is the world that changes – if only for that moment” wherein we truly believe in an ideology or community that we may otherwise dismiss (Chamberlin 239).

“Riddles highlight the categories of language and life; charms collapse them. Neither does away with them” (Chamberlin 239). This, I think, is what Brecht was trying to achieve as well, trying to drive a wedge between realism and artificiality so that we may explore the liminal space of our instinct to categorise. Words “make us feel closer to the world we live in” because we inhabit a world of contradictions, and language requires us to become comfortable in the practice of believing and not believing at the same time (Chamberlin 1). It is only by achieving this balancing act of embracing contradiction that we are able to move forward into finding common ground.

Works Cited:

Chamberlin, J. Edward. If This Is Your Land, Where Are Your Stories? Finding Common Ground. Toronto: Vintage Canada 2004. Print.

National Theatre Discover. “An Introduction to Brechtian Theatre.” Online video clip. YouTube. YouTube, 26 July 2012. Web. 22 May 2014.

Thury, Eva. “Brecht on Alienation (the A-effect, or, from the German Verfremdung, V-effect), an Essential Element of Modern Drama.” Web. 23 May 2014.

Hi Jess – 🙂 I will just say hi for now and come back to hopefully find some comments later this week. Enjoy

Jess! What a wonderful blog post – thouroughly enjoyed all of your insights, your theatre background gives your analysis a really unique perspective. Liminality is one of my favourite concepts – I especially loved what you said about the “space of our instinct to categorise.”

As I made my way through Chamberlin’s book, I kept thinking about plurality – how, for most of us, the binaries that he discusses (reality vs. imagination, us vs. them) are lived on a spectrum. It’s interesting to think about the colonialism and oppression that pervade these categories – and how they are all bound by the rigidity of language.

I feel like both Chamberlin’s discussion of words/language and your careful analysis of these concepts are both inextricable from the other main theme of the work – what constitutes ‘home.’ I would be interested to hear what your thoughts are!

Liminality is one of my favourite concepts, too – so much magic to be found therein! Other aspects of my life (clowning, bodywork and massage, yoga) also deal with the subtlety of in-between spaces, and it’s fascinating.

Language is such a funny thing. Even discussing liminality and the problems of binary thinking are confounded by the English language (the language of colonisation). How are we to transcend this thinking when our very language limits our thinking? Just as the fact that our language has no natural gender-neutral pronouns (although we’re working on it…) makes it difficult to melt the concept of a gender binary, so too is it challenging to discuss Us and Them, reality and imagination, savage and civilised within the constructs of a language whose very structure relies on binaries. So yes, talking about spectrums and continuums is an essential part of the process of decolonisation within the self – not to mention the wider community.

Home has always been an interesting concept for me. I was born in Vancouver, then moved to England for seven years, before moving back to Canada with my family when I was 14. Upon moving back (to the Sunshine Coast, to be precise), my parents divorced, and from that time on my sense of home has been split between people, houses, and codes of conduct that differed in each environment. I realised later, after having moved back to Vancouver for university, that for a long time – even before my parents split up – I have located ‘home’ in people rather than places. Now, my mother and sister live in England, my father on the Sunshine Coast, and my brother in Lynn Valley. I am used to missing people – but I am also accustomed to having ‘home’ spread all over the world. I’ve learned to build home within a community, and within my own habits and patterns of being. I find home on the yoga mat, in the shower, in the studio, in the forest, in the company of loved ones, in a good cup of tea; it’s always evolving. The more I get to know myself, the more I find my sense of home. Here, language fails again! Words can’t quite seem to encompass my relationship to home – it’s too complex, and it confounds the idea of a binary. There is no ‘home’ and ‘not home’, because my life has forced me to learn to construct my own home within myself wherever I go. I realise this is a very personal response to an otherwise theoretical question, but I suppose questions about home will always inhabit a personal sphere. I never really took the time to articulate this before – thanks for making me think, and forcing me to put it into words.

Lovely to read your response. Can we be friends and get coffee and talk about these things in person? Please.

Yes please! I will befriend you on the book of faces.

Hi Jess,

I really like the way that you use theatre to illustrate Chamberlin’s idea of the fine line between reality and artifice- it gave an interesting perspective to Chamberlin’s argument. I too found much of what Chamberlin discusses in his book to be inspiring, especially the concept of the understanding of language being a balancing act between believing and not believing. That is, language is both real and not real at the same time; a representation and a reality. Language can never truly represent objective reality and yet language (or the way that we communicate) can actually fabricate our idea of reality. Therefore it is crucial that we understand the limitations of language and its hypereality, as it can become dangerous when we validate our own language and dismiss others, resulting in an “us vs. them” mentality. Chamberlin illustrates that this can potentially be avoided, by first recognizing the awkward position language inhabits between the real and the not real and then understanding universality of this position that we occupy. I have never looked at the problem of the “us vs. them” dichotomy in quite this light before and find it very engaging.