“So.

In the beginning, there was nothing. Just the water.” (King 1)

What a wonderful beginning. The opening pages to Green Grass, Running Water hold many of the clues that assist us further on in the text. Because the structure of the novel circles (or, rather spirals) back on itself, King’s opening becomes richer and richer on further readings, and, magically, seems to tell different stories with each revisiting.

“In the beginning” signals a Creation story, the likes of which people have been telling to one another for as long as stories have existed. My Judeo-Christian-indoctrinated mind immediately made a connection to Genesis, but also to the stories my mother told me about the beginning of the world, which were decidedly less patriarchal. The truth is that Creation stories are one of the most essential tools for identifying with community and teaching lessons about our place in the world. I have mentioned the importance of Creation stories before with reference to Leanne Simpson’s theory that the Creation stories we pass on to one another contain the seeds for everything we need to know about life and community.

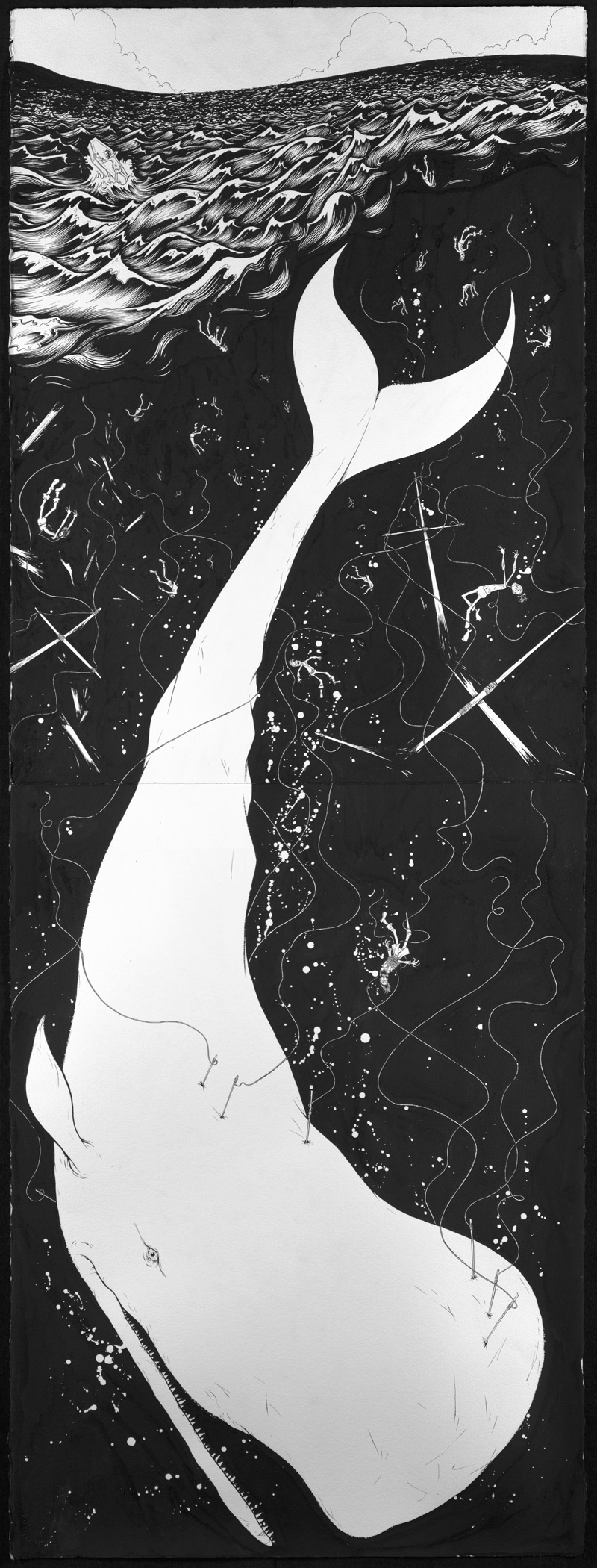

King continues with the creation story, revealing that there was nothing, except the water – and Coyote. This is an important point, because it indicates that Coyote had no creator – s/he simply existed and has existed forever, as long as water and nothingness. Coyote was asleep, however, perhaps indicating that the potential for Coyote was there, but lying dormant. Coyote’s dream, self-important and reckless and a sort of perversion of Coyote energy, runs rampant with no conscious Coyote to keep it in check, and stands in for the Christian god. This sets up the first of many instances in the novel of subverting familiar Christian doctrine to reveal an alternate perspective, questioning and mocking the presumed authority of male figures from Western narratives.

Shortly, the reader encounters the reflexivity of the narrative when the narrator, “I”, engages in conversation directly with Coyote, breaking the fourth wall and indicating that these figures are able to transgress beyond the ordinary bounds of literary convention. There is some question as to whether the “I” is the Creator figure in the text. I am of the opinion that they are – simply because they are telling the story, and the telling is an act of creation. Whether or not there is any definitive god figure is up for debate, and I am personally of the opinion that everything in the text is an expression of god; the narrator figure is simply performing a necessary role, but everything in this world is an aspect and representation of the Creator.

Page 4 greets us with (what looked to my untrained eye) beautiful but foreign writing. When I first read the book several years ago, it registered simply as a series of attractive black squiggles on a cream page. Isn’t that what all writing is, after all, until we learn to decipher the symbols? It reminded me of being a small child, gazing in wonder at the mysterious squiggles on pages that held the key to worlds of adventure and information. This displacement, and the defamiliarisation that the writing provokes, reminds me that I am not in the world I am used to: I am a visitor on someone else’s territory. I think this strangeness and potential discomfort is important for settlers like myself to experience because it de-centres the privileged group from the conversation to make room for narratives that are being gifted to us from another culture.

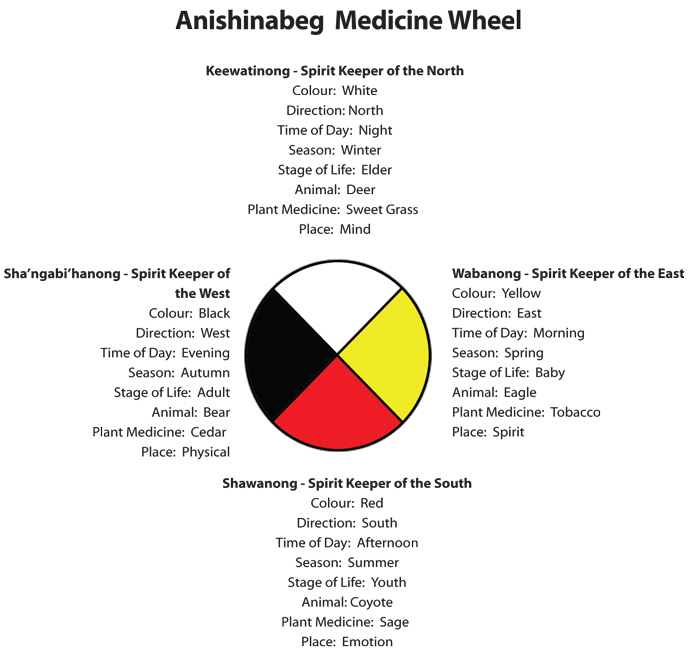

These title headings are, of course, references to the Medicine Wheel, which represent the seasons, the four cardinal directions, and four aspects of human experience, among many other things.

The first part is East. East represents Spring, new life, and calls for the recognitions of the interconnectedness between all beings and things, and also recognising the importance of all human senses in knowing (Chisila 183). This part of the wheel is about spiritual experience, childhood, and new beginnings. In her “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water,” Jane Flick quotes Peter Powell’s Sweet Medicine: The Continuing Role of the Sacred Arrows, the Sun Dance and the Sacred Buffalo Hat in Northern Cheyenne History to describe the qualities of each direction, noting that “the East represents the new generation, still green, and just beginning to grow” (Powell, qtd in Flick 143). This gives us some clues into the nature of the following section: we’re setting up beginnings, telling the stories about how we got to where we are today, and setting the ball rolling to embark on this adventure. These stories are just beginning, and King uses the qualities of the Medicine Wheel to frame the storytelling.

It is natural, then, that we begin with Lionel trying not to fall asleep at the wheel as his Aunt Norma asks his opinion about carpet colours. He is straddling the boundary between consciousness and unconsciousness, being and not-being, the place of being born, which is arguably the place of spirit.

The most interesting part of this mini-segment, to me, is the last two lines:

“Everybody makes mistakes, auntie.”

“Best not to make one with carpet.” (King 8).

Because this is right at the end of the introduction to the first realist characters we meet, I find those two statements reverberating in my mind: clearly they are important. In such a simple gesture, King sets up a theme of mistakes and differing value systems which he later weaves masterfully into his narrative. Those two sentences are dynamic and revealing without telling too much. Here, too, he manages to touch on the importance of orality, as they are almost audible. I can almost hear the words in my mind when I read them.

Next, we turn to the Lone Ranger, Ishmael, Robinson Crusoe, and Hawkeye to carry us further into the story. This is the Lone Ranger’s take on the events, and s/he clearly has some trouble rallying her compatriots and settling the scene. In the brief dialogue between the four of them, many hints are revealed about the end of the novel, including “the jacket” which turns up later in the John Wayne film and as a birthday gift to Lionel, which is also the appropriated property of George Morningstar; “turn[ing] on the light,” a reference to Genesis, and “the apology” that Coyote must perform (King 9). Right here at the beginning, King establishes the circular structure of the story – although we won’t know that until the end.

Next, we turn to the Lone Ranger, Ishmael, Robinson Crusoe, and Hawkeye to carry us further into the story. This is the Lone Ranger’s take on the events, and s/he clearly has some trouble rallying her compatriots and settling the scene. In the brief dialogue between the four of them, many hints are revealed about the end of the novel, including “the jacket” which turns up later in the John Wayne film and as a birthday gift to Lionel, which is also the appropriated property of George Morningstar; “turn[ing] on the light,” a reference to Genesis, and “the apology” that Coyote must perform (King 9). Right here at the beginning, King establishes the circular structure of the story – although we won’t know that until the end.

The Lone Ranger begins “Once upon a time…” and is reprimanded by their compatriots for getting the beginning wrong (King 11). This is a recognisable beginning of many Western fairy stories, but the other character’s rejection of this beginning indicates that we are in different territory, telling the story of a different culture. It also establishes the importance of beginnings, which brings us back to the vital task of telling Creation stories, and telling them right.

“Best not to make [a mistake] with carpet,” Norma says, but King might as well say that it’s best not to make a mistake with beginnings, because they form a foundation for the rest of the story (King 8).

Works Cited:

Chilisa, Bagele. Indigenous Research Methodologies. Thousand Oaks, Calif: SAGE Publications, 2012. Print.

Favorite, Mary R. “Medicine Wheel.” Anishinaabemodaa – Ojibwe Language Website. June 27, 2011. Web. July 28 2014.

Flick, Jane. “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water.” Canadian Literature 161-162 (1999): 140-172. Web. 17 July 2014.

“Genesis 1.” Bible Gateway. Web. 28 July 2014.

King, Thomas. Green Grass, Running Water. Toronto: HarperCollins P, 1993. Print.

Marlow, Jess. “Double, Double, Binary Trouble.” ENGL 470A: Our Home On Native Land. UBC Blogs. 25 June 2014. Web. 27 July 2014.