Question #3: Examining narrative decolonisation in Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water.

Throughout the novel, King cleverly picks apart and reinterprets a variety of narratives that are familiar to anyone who has been indoctrinated with Christian narratives (i.e., most people in North America at one point or another) to highlight the patriarchal, heteronormative, and strictly rule-oriented themes that characterise European cultural discourse. The two stories that I want to focus on are Changing Woman’s encounter with the Moby Dick story and Old Woman’s conversation with “Young Man Walking On Water”.

From the moment Changing Woman arrives on the Pequod, her frankness and unapologetic Indigenous – not to mention feminine – identity interrupts the expectations of the other characters on board, to the point that they are unable to recognise her for who she is. Instead, they cast her in the roles that they are comfortable with, renaming her Queequeg with blatant disregard to the truth of her identity and experience.

Changing Woman is unable to understand the motivation behind killing whales, and Ahab assures her that in a Christian world, “we only kill things that are useful or things we don’t like,” which, according to Margery Fee and Jane Flick, “covers just about everything” (King 196, Fee and Flick 135). This goes some way to making sense of the relationship that white settlers/explorers have towards Indigenous peoples; Indigenous survival relies upon walking an impossibly thin line of approval that revolves around the whims of an invading group of people. This kind of petulant intolerance reminds me of a child’s temper tantrum, or of the terrifyingly volatile Queen of Hearts from Lewis Carroll’s Wonderland, whose favourite expression is “Off with their heads!”

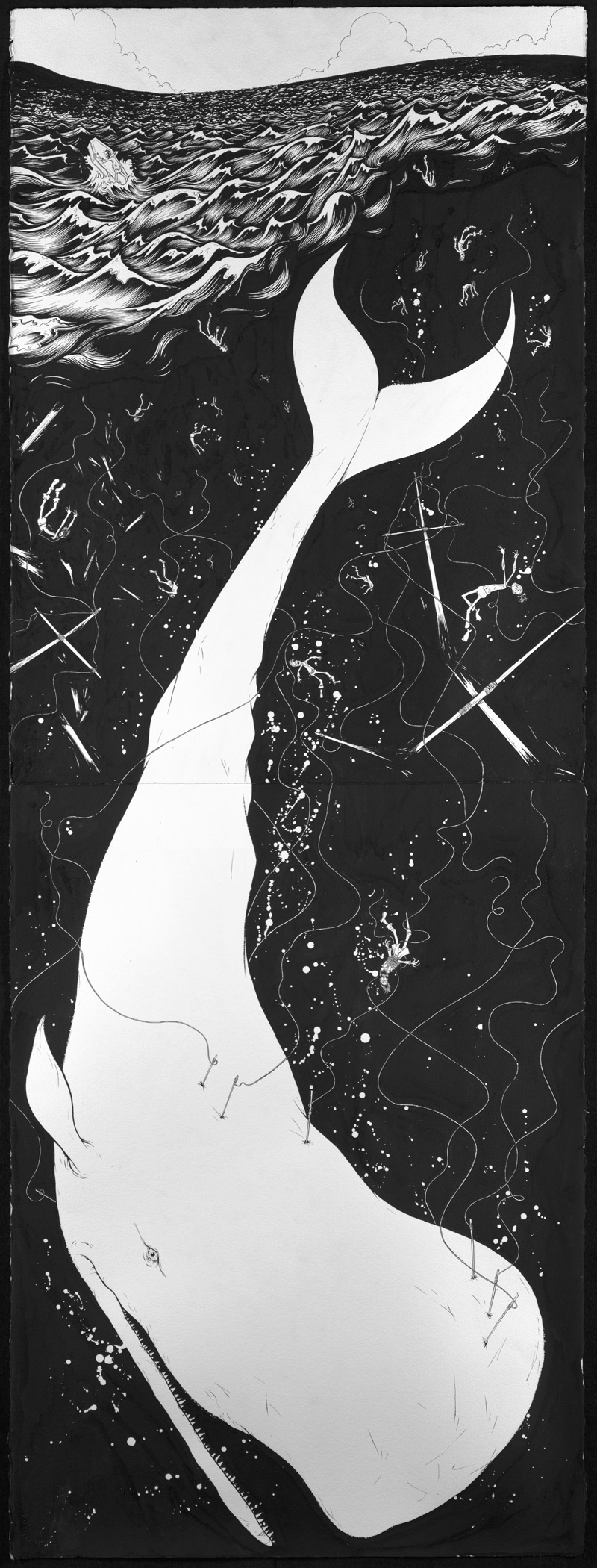

Coyote recalls the traditional story of “Moby Dick, the great white whale who destroys the Pequod,” but the narrator’s reminder that “it’s English colonists who destroy the Pequots” creates a useful parallel from which to discuss recurring themes of violence and subjugation towards Indigenous populations. This play on Pequod/Pequots “reminds Coyote that he may have been reading part of the Western canon, but he ought to have been reading Native history: Moby-Dick covers over a white society that killed its foes, sold all the survivors into slavery, and abolished the use of any Pequot names, effectively wiping out any record of them.” (Fee and Flick 136).

Moby Dick positions nature as a destructive force with humans (read: white men) as its victims, while King’s re-envisioning highlights the violence and cruelty with which white men treat the natural world. European narratives are consistently anthropocentric, imagining humans to be separate from and at odds with the natural world, while Indigenous narratives tend to place humans as part of a natural system.

King’s efforts at decolonising the Moby Dick narrative also involves highlighting the invisibility of blackness, femaleness, and queerness in European patriarchal society. As Margery Fee and Jane Flick note, what we have here is “an attack on lesbians and the refusal to recognize black-ness,” as Ahab throws overboard anyone who sees Moby Jane for what she is (black, female, lesbian) and insists on the whale’s whiteness and maleness (135). Changing Woman is instructed to pick up a harpoon, but instead jumps overboard and joins Moby Jane for an erotic ride through the ocean, “swimming and rolling and diving and sliding and spraying” (King 224). The great adventure about men and male domination becomes a story about female relationships and eroticism that is completely independent from male influence. “This inability to see blacks, females, lesbians as people explains why no one [except Babo] has noticed that the four old Indians are women; because they act like men, they have been mapped on to male mixed-race pairs of Western literature that operate on the hierarchical model of the Lone Ranger” (Fee and Flick 135).

Another element of Indigenous narratives that has been layered onto this European story is the cyclical nature of events. Moby Jane remarks to Changing Woman that she and Ahab have the same battle every year. “He’ll be back,” she says, “He always comes back,” and when she leaves Changing Woman in Florida it is because she has a duty to go back to sink the ship again (King 197). There is a quality of long-suffering patience to Moby Jane’s attitude, as if she were a mother indulging a small child’s request to read the same story again and again. Clearly, she performs this service for Ahab’s benefit, not for her own. Instead of considering this a cyclical narrative that loops back on itself pointlessly without progression, I consider it a spiral, as each turn of the wheel brings new insights and development. We can trust that the whale will repeat the cycle as many times as necessary for Ahab to learn the necessary lessons.

When Old Woman encounters Young Man Walking On Water, it is clear to anyone who has had any exposure to Christian doctrine that the man she meets is Jesus, but King defamiliarises his identity by renaming him – denying him his chosen name just as Indigenous figures have been denied their own names. Contrary to Biblical teachings, Young Man Walking On Water is characterised as forceful, proud, masculine, and determined to be self-sufficient. As in all the stories that the four mythical women encounter, there is an emphasis on Christian rules that consistently privilege white maleness and ignore feminine autonomy and wisdom. Jesus attempts to save the men in the boat by ordering the waves to submit to his will, but Old Woman rebukes him for his domineering attitude: “You are acting as if you have no relations,” she says, highlighting the importance of respect for one’s elders, and also a sense of familial connection to the natural world (King 351). Instead of forcefully working against nature, Old Woman works with the waves, singing a song to soothe them so the men in the boat can be rescued. While the men in the boat are grateful for being rescued, they are unable to recognise that a woman could have exercised the power to save them, and so they default to masculine authority and credit Jesus for their rescue (King 352).

Another notable aspect of this story is that the narrator dismisses the authority of textual narratives. Coyote repeatedly proposes story elements taken from the Bible; “Forget the book,” the narrator says, “We’ve got a story to tell,” indicating that this narrative transcends the written word, and that oral stories can carry more validity than text.

Telling these familiar European stories of masculine conquest with an Indigenous twist defamiliarises them and sheds light on the strangeness of the rules that govern Christian doctrine, highlighting in particular the way European narratives present a disconnection between humans and the natural world. The mythical women who fall from the sky repeatedly encounter other characters and situations that diminish or ignore the wisdom of women and Indigenous people. King’s narrator acknowledges that the stories that the four old Indians are telling are all the same: they are spiralling around themselves, telling the same story from different perspectives, looping back around time and again, just like Moby Jane, for as long as it takes for us to learn the lesson.

Works Cited:

Fee, Margery and Jane Flick. “Coyote Pedagogy: Knowing Where the Borders Are in Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water.” Canadian Literature 161-162 (1999): 131-139. Web. 14 July 2014.

Gingerich, Jon. “The Spiraling Narrative.” LitReactor. 26 April 2012. Web. 15 July 2014.

King, Thomas. Green Grass, Running Water. Toronto: HarperCollins P, 1993. Print.

“Off With Their Heads! — Allen (1985).” 30 September 2012. Youtube. Web. 16 July 2014.

Hey Jess,

Thanks for this post and breaking it down so well. I think this section brings up some of the great differences of the two leading societies in Canada, highlighting the great polarity in values and understanding such as matriarchy and its contrast to patriarchy. The treatment and attitudes towards nature also reminds me of the arguments about the ‘state of nature.’ French philosopher Rousseau criticizes Thomas Hobbes belief that man is above nature by rather saying that it is in nature that humanity is truly free. As the English were highly influenced by Hobbes, I wonder how their approach to colonization would have been different if they were more influenced by Rousseau. I also wonder what the connection to the French colonizers in Canada was to Rousseau at the time because it seems that their approach to the First Nations was also quite violent and disrespectful?

Hi Bara,

You make a great point by bringing Hobbes and Rousseau into the discussion. Even though the French may have been influenced by Rousseau, any expectation on our part for them to be kinder for the Indigenous people they met is reliant on the assumption that they considered the Aboriginal inhabitants of the land to be people in the first place. Even though they may have thought that true freedom was found in nature, my (admittedly cynical) mind can’t help but assume that the freedom they were seeking was their own, not that of the Indigenous people they encountered.

I wonder if it would not help to turn to some Indigenous narratives and prophecies (such as the 8th Fire Prophecy) to shed some more light on the way Indigenous people viewed first contact and where we can go from here.

This was a really detailed and analytical blog post 🙂 I also wrote on Young Man Walking on Water for one of my blog posts and Prof. Paterson linked me over and said your analysis was definitely worth reading. I thought this line from your blog was particularly insightful:

“Telling these familiar European stories of masculine conquest with an Indigenous twist defamiliarises them and sheds light on the strangeness of the rules that govern Christian doctrine.”

I like how you don’t say European stories and indigenous ones contrast each other. Rather they defamiliarize and make you step back and acknowledge the absurdity of some of the things that govern Christian doctrine.

Thanks Leo, I’m just about to go over and read your post – I’d be interested to hear what you have to say!

And yes, I am often hesitant to set two cultures up in opposition to one another, as I believe that that approach can only lead to antagonism and an “us vs them” mentality. Instead, if we can learn to see different perspectives and remove the dominant group from the centre of the narrative, it gives us an opportunity to appreciate that we are all as strange as one another, and just as human.