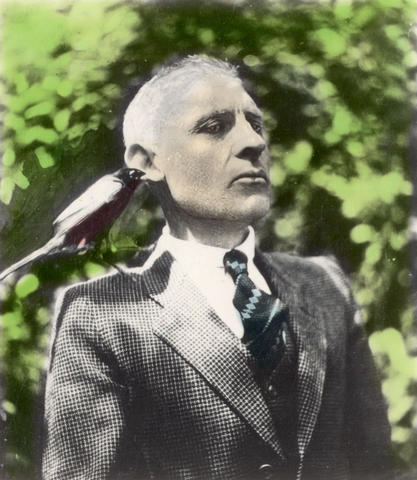

James Skitt, Matthews, Major. For all the world Bob “peels” the Bell; Rings out the old ‘ear–makes the New ‘ear “swell”. 1938. Photograph. Charles E. Jones and family. searcharchives.vancouver.ca. Web. 2 June. 2014.

As I head to the radio station with my last minute story, if you could call it one, my cell phone vibrates with a new text message from the producer.

Just thought I will let you know that we will be recording in studio 22 instead of 21. We’re really looking forward to hearing your story. See you in a bit!

I did not intend to write this story. I started out with a draft about a father with an addiction to alcohol and two sons. When news broke out last night about a drunk shooter at the local strip mall killing five passersby, I knew I had to come up with something new, or at least something else.

I did not intend to tell the story but I tell it anyway.

There was a group of birdwatchers, and this was their first time meeting one another. They have met through a classified posting, which one member of the group had put up a month ago on the community notice board. The five birdwatchers had nothing in common, except for their intention to compete in the National Geographic annual photography contest, and their fear of being killed by a madman.

Any experienced birdwatcher would know that it would be counterintuitive to chase birds in a group. Most of the time, birdwatchers go out alone, or in a pair. However, since the news of the serial killer broke out, not even the mesomorphic, free-spirited, young man wanted to wander around Beacon Hill Park alone.

There has been no witnesses, who has come forward, and no bloodstained objects has been discovered in the vicinity of the found bodies. The only thing the authorities claimed to know, was that each body had exactly five stab wounds. It’s been six months since the discovery of the first body, and the killer was still at large, free as a bird. By the time of the birdwatching trip, there was no lack of stories going around. The island is huge but it was a village back then. Everyone was related by blood or acquaintance.

There was a story about the killer, who picked his victims randomly at bars because all of them had a good number of empty bottles in their garbage, but at that time, who didn’t? And there was another story about a Bay employee, who committed all the murders because the five male victims were her ex-boyfriends. The speculation was so persistent that a bunch of elementary school kids bullied the suspect’s daughter to death. She was found on the floor of her school’s washroom five days after the rumour started. It was later revealed that the suspect was a lesbian and her daughter was not even her biological offspring.

The birdwatching group was going to start on Dallas Road, walk to Beacon Hill Park, and head to Rocky Point on a rented van. But a sudden downpour had forced them to duck under a gazebo on Beacon Hill until the rain relented. The man, who posted the ad at the community noticeboard and organized the whole trip, began some small talk, and the conversation gradually advanced to the evil killer drifting around the island without a shadow. A few members of the group began taking out their packed lunch to distract themselves from the chills.

“I don’t think he is actually from the island.”

“He? I can bet you the serial killer is a crazy bitch, who lost her trailer park boyfriend.”

“Where do you think he actually kills his victim since the police are saying that they were not killed at home? A barn perhaps?”

“Do you think this guy has a day job? Or a hobby? Or may be killing is his hobby?”

“Probably some creepy ass shit like assembling miniature dollhouses.”

“Wouldn’t it be funny if the killer was actually a birdwatcher too?”

The group broke out in brief, polite laughter.

“What if the killer was actually a part of the group? Haha.”

The laughter died down and the rainfall took over conversation again.

When everyone reverted back to staring at their ham and cheese sandwich, the man who posted the ad took out a spear-pointed knife from the back pocket of his rucksack. Everyone edged to the periphery of the gazebo, subconsciously and irrationally hindered by the rain as if getting wet was worst than being dead.

“If you’re the serial killer, you better come forward now. I don’t want to die yet, I will take the chances and kill all of you before I let myself be killed,” said the man with the knife.

“Put the knife down, man. No one is the madman here. We’re just here for the birds.”

“Yeah. And the weather isn’t cooperating anyway, may be we should do this some other time.”

Everyone nodded in agreement, knowing that they will never do this again, but not for the actual reason that determined this their last birdwatching expedition.

“Jason Pierson is a writer, and ornithologist based in Victoria, British Columbia. We will return after a short break, to learn about the fate of these birdwatchers.”

Elijah turns off his microphone, and turns to me. “Hey Jason, not sure if we didn’t communicate clearly enough, but we wanted original writing. We don’t do creative non-fiction here. Your story is just the birdwatching incident in 1955. What’s up with that?”

“What if I told you that my story—or the “retelling”—of the event has actual details about the event that has never made it to the public before? Would my story be worth telling then?”

I begin with the engraving on the knife, and the constellation of moles on their bodies. Then there was the precision of the incisions, and the oozing of the guts, in details as vivid as my obsession with crossword puzzles enables me. Everything, except for the rationality because there was not any known to me.

“But where would you have gotten this information after all these years? All but one person died in that mass murder . . .” Before Elijah could finish the sentence, he freezes. So did the producer, and the sound engineer, whose fingers are still fastened to the buttons of the sound board.

“If I had known you would react this way, Elijah, I wouldn’t have told the story,” I say to his now bloodless face.

“I wish I haven’t heard it either,” Elijah says as his fingertips touch the edge of the telephone. So I do what I have to do, the same thing I had to do, when I was a teenager.

As the producer, the sound engineer, and Elijah’s eyes blink for the very last time, I realize a red light has been beaming quietly in the corner of the studio.

Recording.

Recording.

So I do what I haven’t had the guts to do, the same thing I should have done when I was a teenager.

-Kayi Wong

Continue reading →

![Matthews, James Skitt, Major. Hugh Matthews, son [of] Major Matthews, panning gold Similkameen River, near Princeton, 1919 or 1920. 1919/1920. Photograph. searcharchives.vancouver.ca. Web. 18 June. 2014.](https://blogs.ubc.ca/kayiwong490a/files/2014/06/fb63d58b-97c3-4319-85fd-cf38b09284ed-A71051-300x174.jpg)