“Yet I cannot let post-colonial stand—particularly as a term—for, at its heart, it is an act of imagination and an act of imperialism that demands that I imagine myself as something I did not choose to be, as something I would not choose to become.” (King 190)

These are perhaps a few of the most powerful words I have read about colonialism.

Thomas King writes in his essay “Godzilla vs. Post-Colonial” that Harry Robinson’s stories, although told and written in English, are crafted with an “oral voice” through “patterns, metaphors, structures as well as the themes and characters [that] come primarily from oral literature” (186). So it was no surprise that the moment I began to read Robinson’s story, I had the desire to read the story aloud. However, as much as I would like to think that, that very initial inclination came from the storyteller’s intention, that is not the case. As a person, who grew up as a colonized member of a colonized land, the moment I was faced with Robinson’s story, it instantly reminded me of the western tradition of poetry (which in itself compels me to read aloud out of habit). That instinct is not biological, but born out of the socialization and colonization of western education. The form itself reminded me of English poetry, simply because of my reading and educational history. It is unfortunate but as much as I attempt to remove myself from a colonized point of view, my way of reading and analyzing Robinson’s text/story is very much rooted in an experience of reading and analyzing writing written in English. I cannot undo the socialization I have experienced, but I will attempt regardless.

As King suggests, Robinson’s story compels his readers to read the story out loud. The sentences are compact, and succinct. They seem like statements of observation collected over a period of time, instead of one particular moment. They are dialogue, but even in the portions where sentences are not in quotations, they sounded like an ongoing conversation.

Who?

What is it?

Looks like a person.

The Little boat’s got a little shack there.

Never see that before.

(Robinson 65)

Most importantly, the oral syntax as embedded in the story by Robinson creates the effect of a story as told by more than one singular perspective, voice, narrator, or storyteller. This is a powerful design because it allows me (the westernized/colonized reader) to be able to understand and read this story, as least to a certain extent, as separated from the traditional western form of poetry. The orality of the story has the effect of a story told by a conglomeration of people and voices, which also echo King’s point about a category of Native stories—Associational Literature. As King explains, this term refers to literature that avoids a “flat narrative line”, and one that “leans towards the group rather than the single, isolated character, creating a fiction that [is] . . . in favour of the members of a community” (King 187).

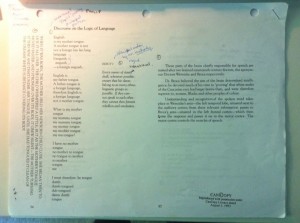

When I discussed the story with a friend of mine, we realized that the storytelling works much better when both of us were sharing the reading. For once, sharing the storytelling was helpful because Robinson’s story is lengthy, but it also highlights that fact that a story cannot be told by one person alone. A story with a singular point of view, and narrator is very typical of western tradition when it comes to literature. So even though the form of Robinson’s story initially reminded me of traditional western literature, by reading it (silently, and out loud with a friend), it distinguishes itself (for me, the colonized reader) from other English literature, while he was working “within the confines of written language” (King 186).. This reminds me of another Canadian poet, and writer M. NourbeSe Philip, who illustrates the theme of marginalization and ethnocentricism through the re-working of conventional “English” poetic forms in “Discourse on the Logic of Language”.

Edit: I’m including an excerpt from Phillip’s poetry since I couldn’t find one online. This is an excerpt, not the poem in its entirety (as I’m not too sure about the copyright laws in private blogging)

Works Cited

![Matthews, James Skitt, Major. Hugh Matthews, son [of] Major Matthews, panning gold Similkameen River, near Princeton, 1919 or 1920. 1919/1920. Photograph. searcharchives.vancouver.ca. Web. 18 June. 2014.](https://blogs.ubc.ca/kayiwong490a/files/2014/06/fb63d58b-97c3-4319-85fd-cf38b09284ed-A71051-300x174.jpg)