I’ve moved this blog to be hosted at my podcast website. All new content can be found at www.lessonimpossible.com/blog!

I’ve moved this blog to be hosted at my podcast website. All new content can be found at www.lessonimpossible.com/blog!

Have you ever given students ten minutes to write, only to realize that they’ve only written three lines? It’s not that they’re being uncompliant, they just “don’t have any ideas”, or, for many students with negative language-learning experiences, they are scared to write anything if it’s not perfect. This is where getting into the habit of doing a “quickwrite” is useful!

I love starting a class with a quickwrite, especially if we’re not starting with a sharing circle. It eases us into the day, and gets us in that French mindset. It’s also a great reminder for students, because I repeat it again and again, that it’s about communication and not about being exact! If students don’t know a word, they don’t stop and look it up, they just put it in English between brackets or virgules, and look it up or ask after the quickwrite is done. The whole idea is fluidity of thought, not worrying about mistakes, and realizing how much you actually know when you’re pushed for time!

If we’re going to be talking about specific content, it’s also a great way to get the students thinking about ideas. For example, I do a technology unit, and there are A LOT of great discussion questions: where measure of privacy should we expect? how should we treat robots when AI inevitably become sentient? Is the use of parental controls fair? And on and on. For the students who don’t like spontaneous discussions, and need time to ruminate before speaking, putting it all down in a quickwrite is a way to put them at ease.

So what are some good quickwrite prompts?

What do we do with them when the ten (or however many minutes you choose) are up?

How do you use quickwrites in your classes? How long do you usually give students? Feel free to comment!

I think a lot about language revitalisation. In fact, I have a whole blog post here.

Obviously, I think it’s an important conversation to have with students as well. I was volunteering with foreign exchange students during COVID, and developed an activity package and facilitated a very interesting session where we discussed this issue! I’ve decided to post it the blog(it’s more of a social studies resource than a language one, but it can be adapted! Or left for a sub who doesn’t speak the target language!)

The activity has four parts, along with multiple extension activities:

Feel free to pull whatever you’d like to use, personalize it to your students, or do whatever! I’ve used the Marie’s Dictionary video with my language students and had GREAT discussions. I’ll let you guys know if I translate this into French!

RESOURCE: Language Preservation Activity 2020

This is Part II of my two-part entry on using Genius Hour Projects! Part I can be found here, which explains why I love these projects so much!

Note: I exclusively did these projects with my senior students as a way to showcase their five years of language learning. This was because French 12 was an elective, so students had chosen to be there, students were capable of doing self-directed work, and their language ability was such that this was possible. However, I do think there’s a way to adapt this for lower-level language classes, if you’re willing to try.

Step One: Introduce the project to students

This was done in the first couple of weeks of class. I had a powerpoint where I would start with a turn-and-talk about the idea of ‘genius’ and how it’s all in the eye of the beholder, and include one of the most well-known teacher cartoons of all time:

Tout le monde est un génie. Mais si vous jugez un poisson sur sa capacité à grimper à un arbre, il passera sa vie à croire qu’il est stupide – A. Einstein

We would then watch a video explaining genius hour, and some other YouTube inspirational stuff. Sometimes I would do some creativity exercises (I’ll post some soon). Then, I would explain the project and have students start to brainstorm what they’d like to do. I’d explain to students that this was in lieu of a final exam, and a chance to showcase everything they’d learned in French.

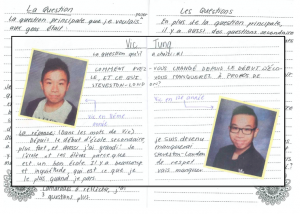

Students would submit an ‘application’ for approval of what their project would be. Once approved, they would write their inquiry question on a piece of paper which we affixed to a bulletin board on one of my walls. Since I had multiple classes, it was cool for them to see what other people were working on! I could also put up any updates or messages about the genius hour projects on that board.

RESOURCE: Project hand-out/application: Genius Hour Proposal

Step Two: Work on it throughout the semester/year

This was the hard part, as I always felt like I had too much curriculum to cover, and not enough time. However, the more time I gave for students to work on the project in class, the better their projects would be. Moreover, the more time I had to check-in with students and see how they were doing, guide their project, and do small, informal conferences, the easier it was for me to mark the projects! Giving students a heads-up was invaluable, as many of them had a lot of material they wanted to bring in to work with (I loved seeing students, for example, pull out a block of wood and start carving!)

There was a lot of ways to incorporate current lessons, such as starting the class with a chance for students to chat about their project’s progression using, for example, four adjectives or in the past tense. Mostly, though, I just enjoyed seeing them do their thing!

Some students used blogs, which was a great way to keep an eye on what they were doing if I didn’t have time to check-in during class

This was also FANTASTIC if I knew I was going to be away for a meeting. I’d tell students that they’d be working on their genius hour projects on X day, and then my substitute plan was just an explanation of the project and directions to supervise so I didn’t need to worry if my replacement spoke French or not.

I would also do goal-setting and check-in dates to keep students on track.

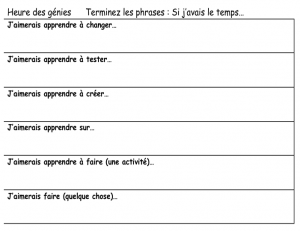

RESOURCE: goal-setting form: L’heure de genie goal setting

RESOURCE: check-in form (mid-way through project): Genius Hour Check-In

Step Three: Presentation time!

At the end of the semester I was lucky in that we ended up doing these HUGE half-day classes (2.5 hours) in the last week so everyone could present. Before that, I would do 3 rounds of 20 minutes in an 80-minute class. So students would be at “stations” (usually 5-6 at a time) and the other students would wander around to check it out and ask questions (see below). Then, they would ‘switch’ and new stations would be set up, so the focus was only on 5-6 students at a time, usually talking to 3-4 students at a time.

RESOURCE: Questions prompts for students to use in a variety of tenses: L’heure de génie questions

A few times I invited other classes to come check out the projects. This was great if I could get grade 11 students since a) it was good advertisement for taking French 12, an elective, which meant I got to keep my job and b) it allowed the students to present to an audience that hadn’t seen the progression of their project. I also invited the administration (as a new teacher, great to showcase cool things you’re doing) who were allowed to ask questions in English or French. My favorite, of course, was when students would bring their pets or bake yummy things to share!

During this time I would go around eaves-dropping and interacting with students so that I could give them a speaking mark based on their fluidity and vocabulary use. I found that I had enough time to get a good sense of students’ abilities during the time we had, though another option would have been a 1-on-1 scheduled appointment for an oral interview. I run a pretty interactive class to begin with, so I had also heard students speak daily for the entire semester.

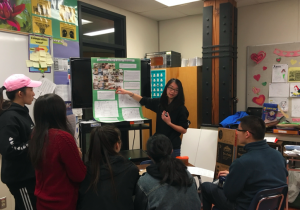

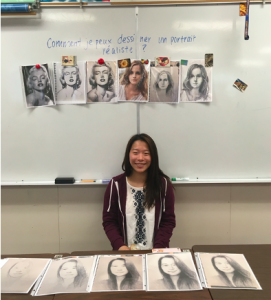

Student presenting to peers; me spying and taking pictures

Then, I would do a mad scramble for evaluating the written part before submitting my marks. I also had students do self-evaluations. Depending on the students I would have certain criteria (demonstrate certain tenses, use vocabulary from our musique mercredi weekly assignments, etc.) Because I wanted in-depth feedback, students had the option of doing their self evaluation in English or in French.

RESOURCE: Genius hour evaluation: Genius Hour Rubric

RESOURCE: Genius hour self-evaluation: Genius Hour Self-Eval

This is Part I of my two-part entry on using Genius Hour Projects! Part II can be found here, which explains my three-step process for doing these projects, along with all my rubrics and hand-outs.

What’s a genius hour project you ask? Well, this video does a pretty great job explaining it. Basically, it’s a project that lasts the entirety of a school year/semester and is (somewhat) self-directed. Students choose an inquiry question (and some teachers are stricter on the definition of an “inquiry question” than others) and spend the time allotted to answering the question. It’s ‘supposed’ to take 20% of class time, but I’d say what I did was more of a 10%.

Since my goal is language use, I’m pretty open to ANYTHING students want to do. The way I present it is: what is something you would want to spend your time on if you were given extra time in your day? So, I’ve had students teach themselves coding, learn ASL, design jewelry, make a comic book, and research the best type of pet habitat for a hamster and build one for their new pet!

I have students brain storm some things they would do if they had the time

There’s always a research component to the project (or a science-fair aspect). So, one example of a project was a student wanted her family to eat together more often. Her goal was to cook a meal for the family to share once a month. First, she surveyed them on their likes and dislikes. Then, after each meal she elicited feedback (quality of the meal, improvement for next time). She also had “personal testimonials” from her parents and brother about the experience of doing these family meals together, took pictures, put them on a poster board, and then presented about her experience. Another student wanted to have the best dorm for when she went to college the next year. So she found pictures of the dorm she was going to, created all these vision boards of design features, got a budget, priced out what she was planning on buying, and presented on what her dorm would look like. Another student loved magic-realism books so she wrote a magic-realism short story! First, she researched what features made the genre, read books she liked (for me, I didn’t care what language she read it) and then wrote a story! I gave her an option: write the story itself in French OR write the story in English but reflect on the story-making process in French. Because she was a super-star, she did both!

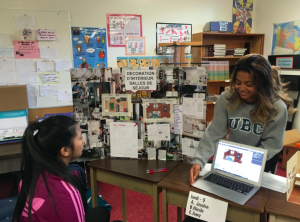

Student planning her dorm for UBC

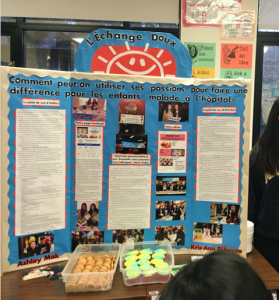

Some projects, because of their free-form nature, can be incredibly personal. One student wrote in a gratitude journal every day (in French) which she later shared. Another student wanted to start a school club for female gamers because she felt excluded from the current (all-male) school club. Her project was about reflecting on that journey (in French) though the club was an English-language club. Another student was currently in a (at that point, year-long) fight with our school board about an anti-bullying policy for LGBTQ+ students (he wanted one), and I gave him the option of reflecting on that process as his genius hour project. A group of two students (I eventually opened up the project for pairs to do bigger things together) used their two original ideas (becoming better at baking, volunteering at the children’s hospital) to fundraise for the hospital through bake sales.

Bakes sales for the children’s hospital

Some projects don’t go so well. Students who imagined writing, producing and filming a short film end up just submitting a script that was never filmed. I’ve seen a half-finished tesla-coil and five-seconds of a stop-motion animation film that was supposed to be a minute (it made me think of this clip from Parks and Rec!). I’m very much a “it’s about the journey, not the destination” person, so I truly don’t care that your tesla coil failed, just that you wrote about the experience and are willing to talk about it with me and your peers in the target language.

Some more examples:

Multiple students have wanted to incorporate a yoga practice into their lives (kept a reflection journal in French):

Student wanted to become more proficient in realistic drawing (kept a progress journal in French):

One student decided to a make a French year-book and interviewed people in her graduating class:

One student decided to a make a French year-book and interviewed people in her graduating class:

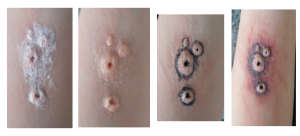

Another taught herself special effects make-up!

I love YouTube videos for class : they are short and entertaining because it’s all about that sweet, sweet ad revenue for the creators. Also, FREE!

I also love using YouTube videos for grammar practice, because practice makes perfect, but rarely fun. Therefore, it’s a great way to have some fun, get the imagination going, take a break from writing for some listening and watching, and use the target language.

A quick and easy way to use a YouTube video is to show and respond to it (no prep needed). However, if you’re willing to put a little time in before hand, you can jazz it up for some fun times. All you need is a word document and the ability to take a screen shot (on Mac it’s command+control+shift+4).

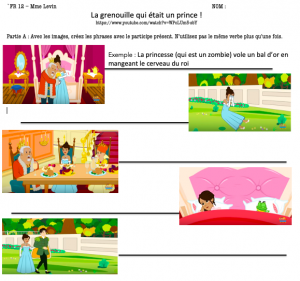

Step Zero (before students): find a YouTube video (either in the target language or one that is mostly silent, like Mr. Bean). For this case, we’re using Le Grenouille Qui Était Un Prince. Take screen grabs of some interesting looking scenes. Make a word document: le grenouille picture story present participle

Step One (with students): students make up sentences (using the grammar structure you want to practice) based on the pictures that they see (DO NOT show the video yet).

You can project the screen captures using a projector if you can only print in black-and-white (as I could only do). That way students can see detail. Encourage students to really stretch their imaginations, don’t rely on stories they already know. For example, the first screen grab is of the king giving his daughter a golden ball, which she will lose, and a magic frog will save for her. Looking at the photo where father and daughter are hugging, we instead decide the sentence will be « La princesse (qui est un zombie) vole un bal d’or en mangeant le cerveau du roi. » (The princess, who is a zombie, stole a golden ball while eating the king’s brains). So, some imagination + using the present participle.

This is a great activity to do in pairs, or groups. Also super funny to share out, since they’ll be unique (unlike the ‘real answers’). You can even have students do a jigsaw activity, going around the room writing down their responses to each photo, and then go celebrate/correct their sentences before the second part of the activity. I like this because they get immediate feedback on the grammar structure before reinforcing it further in step two.

Step Two: Watch the video. Stop after each scene that the picture represents and have students write a sentence that describes what ‘actually’ happened. For example, « La princesse dit « merci » en embrassant son père. » (The princess said thank you while hugging her father <— told you it was less exciting than zombies!). This can be done as an extension/homework if students have access to computers to watch the YouTube video.

The sky is the limit, and once you’ve go the template, it’s easy to replicate. I’ve done this with all sorts of stories, including, as mentioned above, Mr. Bean videos! mr bean wanted picture story – using si-clauses. When I’m in a real rush, sometimes I’ll reuse the stories for other grades/units, just swap in a new grammar concept. While ideally the video is relevant to the unit we’re doing, sometimes you need to plan something for a substitute teacher at 1am, and this is an easy thing to create!

Teaching idioms is an absolute gong show. How so? Well, if you are not a native speaker of English, I would have to explain to you that the first sentence was expressing the chaotic nature of idiom instruction. Then I would have to explain that the Gong Show was a game-show in the 1970s, and that idiomatically, in Canada and the United States, something described as a « gong show » is something that is disastrous, but in a charming way.

Yet, why do we persist in teaching idioms? Partly, it is because it is a marker of fluency, to understand not just the translation of a sentence, but the idiomatic sense of a sentence. It is also seen as intercultural proficiency: to understand a culture is to understand its idioms. What « there’s more than one way to skin a cat » or « let the cat out of the bag » tells foreigners about English’s treatment of felines is probably best left unexamined, but idioms are a great way to examine cultural mores. And lastly, idioms are fun! It’s the best of language: playing with sound and meaning to create vivid images that stick around, sometimes for centuries.

Teaching idioms is one of my favorite things to do, though I think it’s important to be careful that we don’t « otherize » or make broad assumptions about the target culture (as in « what weirdos: all English-speakers mistreat cats »). In French, I’ve got some go-to resources that I’ve created (some I’ve mentioned on the blog before):

My own défis: most of the idioms that I use/teach are from France or Quebec (there’s a significant overlap). It’s a goal of mine to expand my idiomatic repetoire to include idioms from other Francophonie countries. As I make my French courses more culturally inclusive of all the varied French speaking nations and cultures, I hope to have many new idioms to share.

Je suis fascinée par les efforts de revitalisation des langues. Je comprends que la morte d’une langue est naturelle : comme les animaux, les langues évoluent. Cependant, je comprends aussi que, comme les animaux, la globalisation tue les langues plus vite que serait naturelle. En fait, par la fin du 21 siècle, la moitié des langues du monde sera éteintes ! Je pense que c’est important que nous préservions ces langues en voie d’extinction pour beaucoup de raisons, mais de toutes les raisons, celle que me touche la plus, c’est comment les langues traditionnelles tiennent la clé pour accéder à chaque culture unique et permettent des voix uniques à être entendues. Comme Claxton Baker, un locuteur de la langue hul’q’umi’num’, l’a dit : « For myself, I feel that it’s very important as a First Nations person to be able to express myself, my identity and my land in my own language ». ·Les langues traditionnelles peuvent être un moyen d’interpréter le comportement humain et les émotions qui ne peuvent pas être exprimées par une langue dominante, comme l’anglais. Par exemple, la langue cherokee a un mot, « oo-kah-huh-sdee », qui représente le plaisir qu’une personne ressent en voyant un adorable bébé ou un chaton. De plus, des informations culturelles importantes peuvent être trouvées dans les langues elles-mêmes. Ainsi, la perte de la langue peut signifier la perte d’histoires et de lignées ancestrales connues uniquement par la narration orale, ainsi que la connaissance des plantes et des pratiques médicinales. Les locuteurs du lulamogi en Ouganda, en fait, craignent que leur peuple oublie la pratique culturelle importante de manger des fourmis blanches, et avec elle une dizaine de termes spécifiques au lulamongi. Ou, dans les mots de Richard Littlebear, un linguiste et une citoyen Cheyenne qui a rencontré la dernière locatrice de la langue Eyak d’Alaska, Chief Marie Smith Jones : « I felt like I was sitting in the presence of a whole universe of knowledge that could be gone in one last breath ». Malheureusement, cet univers a disparu quand Marie est morte en 2008. Alors, le plus je me penche sur les langues en voie d’extinction, le plus je me demande si j’ai le droit d’avoir une opinion. Je me sens mal à l’aise, en tant que locatrice de la langue majoritaire, de dire aux autres qu’ils DOIVENT préserver leur langue. Il y a beaucoup de raisons qu’une langue n’est pas parlée : la honte ou la peur, un manque de temps ou de ressources, ou peut-être un véritable désir pour l’assimilation. J’écoute un excellent podcast (« Stuff the British Stole ») et une citation de cet épisode m’a vraiment marqué : « It’s an important dynamic within imperialism, that you have a constant nostalgia for the thing that you are in the act of destroying. So at the same time as you disrupt local cultures, and seek in fact to destroy them in order to dominate, you are mourning the loss of those cultures and trying to act in ways to preserve them » (à 20:50). En tant qu’une personne fascinée par la préservation de la langue et qui pense que c’est un objectif incroyablement important, je me demande dans quelle mesure, pour moi, c’est de l’empathie et dans quelle mesure c’est la nostalgie d’une colonisatrice ?

Les sources:

Baker, C., & Wright, W. E. (2017). Foundations of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism (6th ed.). Multilingual Matters.

Fennel, M. (Executive Producer). (2020-present). Stuff the British Stole [Audio podcast]. ABC Radio National. https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/stuff-the-british-stole/best-named-dog-ever/12867932

Nuwer, R. (2014, June 5). Languages: Why we must save dying tongues. BBC Future. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20140606-why-we-must-save-dying-languages

Ouellet-Dumont, C. (2018, February 22). Les langues menacées de disparition. Quel mot t’a piqué? https://quelmottapique.com/2018/02/22/les-langues-menacees-de-disparition/

Paetkau, J. (2019, December 16). Elders and great-grandchildren share the legacy of learning Hul’q’umi’num’. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/originalvoices/language/halkomelem/

Riehl, A. (2019, November 8). Why Are Languages Worth Preserving? SAPIENS. https://www.sapiens.org/language/endangered-languages/

Souvent, mes ami.e.s me demandent si l’immersion est un bon choix pour leur enfant. Aujourd’hui, mes pensées et des faits sur ce sujet :

Les avantages du bilinguisme

Le but d’être bilingue est une bonne raison pour inscrire votre enfant en immersion. Pour moi, il y a beaucoup d’avantages que j’ai vécu en raison de mon bilinguisme. Le plus grand avantage, bien sûr, est l’emploi, mais mon avantage préféré est de découvrir des informations cachées ! Par exemple, dans Harry Potter, j’ai pu voir les noms Malfoy (mal + foi) ou Voldemort (Vol de mort) et mieux comprendre leurs personnages. Mais, c’est moi, et en général, le bilinguisme présente divers avantages qui n’ont rien à voir avec Harry Potter ! Il y a des avantages cognitifs, tels qu’une plus grande souplesse mentale, une capacité de penser plus indépendante des mots, une supériorité dans la formation de concepts, et une intelligence plus diversifiée. Il y a aussi l’avantage d’une conscience métalinguistique. En fait, les enfants bilingues ont une compréhension plus approfondie de la relation entre les mots et leur signification que les enfants monolingues ! En outre, les personnes bilingues ont l’avantage d’une sensibilité communicative. Pour exemple, ils ont les plus grandes sensibilités verbales et non verbales et la plus grande attention aux besoins de leurs interlocuteurs. Plus, elles comprennent plus facilement les insinuations et elles corrigent les erreurs plus rapidement.

Les résultats possibles

C’est important que vous pensiez de votre définition de « bilingue ». À la fin de la septième ou de la huitième année, les élèves de l’immersion française précoce (IFP ou « Early French Immersion ») auront reçu cinq mille heures d’enseignement du français. Lorsqu’ils sont testés, leur compréhension auditive et écrite est similaire à celle d’un natif, bien qu’il soit difficile de faire ce genre de comparaisons. L’écriture des élèves sera discernable de leurs pairs francophones par leurs erreurs de vocabulaire et de grammaire, et leur expression orale sera leur compétence la plus faible, peut-être en raison d’un manque d’interaction avec des francophones. Les élèves de l’immersion française tardive (IFT ou « Late French Immersion ») ne reçoivent que mille quatre cents heures de français, mais les résultats sont très similaires. En écoute, lecture et écriture, les étudiants d’IFT sont les mêmes que leurs pairs d’IFP, bien que leur expression orale ne soit pas aussi forte, peut-être parce qu’ils ont encore moins d’occasions de pratiquer. Cela dépend, bien sûr, si les élèves restent dans le programme. En fait, 50 % des élèves qui s’inscrivent en immersion française en 1re année y restent jusqu’en 8e année !

Le développement du français et de l’anglais

Malheureusement le développement du français se termine lorsque les élèves vont à l’école secondaire. Les écoles offrent rarement tous les cours en français, et de nombreux étudiants en immersion suivent leurs cours optionnels en anglais. Donc, les élèves d’immersion ont l’occasion de conserver leurs compétences acquises en français. Néanmoins, l’immersion au niveau secondaire n’est pas suffisamment intensive pour permettre les élèves accroitre leurs habiletés en français. Plus, une inquiétude commune est que les étudiants prennent du retard dans leurs compétences anglais. C’est vrai que les élèves ont des compétences en anglais moins avancées jusqu’à l’anglais est introduit dans le programme d’IFP. Mais, en huitième année les élèves ont des compétences an anglais égale sinon supérieure à celles de leurs pairs inscrits au programme d’anglais. Si cela est très inquiétant, alors l’IFT est peut-être le meilleur choix !

Les autres options

Il y a le français de bas (FB ou « Core French »). J’ai suivi ce programme, et je pense que je m’en suis bien sortie ! Il y a aussi des écoles qui offrent le français intensif (FI ou « Intensive French »). C’est un programme, souvent pendant la cinquième ou sixième année dans lequel les élèves complètent le programme de FB en moitie d’année scolaire. J’adore ce programme, parce qu’il n’y a pas les mêmes problèmes d’immersion française (une autre entrée pour un autre jour) mais les résultats sont incroyables. En comparaison de FB régulière, les compétences orales des élèves de FI sont comparables aux élèves de neuvième, dixième, et même d’onzième année ! Et en comparaison aux francophones du Québec, les élèves de FI ont une exactitude comparable à 3ième année et une fluidité comparable à 4ième année. Même si le programme ne dure que six mois, par le 12ieme année la majorité des élèves de FI ont obtenu un niveau B1 ou un niveau plus haut.

Références :

Alphonso, C. (2016, May 31). Ontario schools struggle to keep students in French immersion. The Globe and Mail. https://tgam.ca/3icKost

Lazaruk, W. (2007). Avantages linguistiques, scolaires et cognitifs de l’immersion française. Canadian Modern Language Review, 63(5), 629.

Selon ilanguages.org, les différents types de locuteurs/locutrices sont :

Je suis une personne bilingue (l’anglais et le français) mais mon père est un polyglotte qui parle couramment l’anglais, le français, l’hébreu, le yiddish, et le russe. Il est également « confiant » dans six ou sept autres langues. Ce que cela signifiait pour moi en grandissant avec un père qui, lors d’un voyage en famille au Mexique, semblait apprendre l’espagnol pendant deux semaines alors que j’avais du mal à me souvenir de dire « grassy-ass », c’est que j’ai toujours supposé que je n’eusse pas une aptitude pour les langues. Ce que j’ai maintenant appris, c’est que mon père est un cas particulier et qu’évaluer ma vitesse d’apprentissage des langues par rapport au sien était irréaliste et démotivant. Fait intéressant, en parlant à mon père de ses aptitudes, il les voit comme un cadeau ainsi que comme une malédiction. Il dit qu’il a du mal à regarder des films étrangers pour l’histoire et le plaisir, passant la plupart de son temps à analyser involontairement les sons et la grammaire. De plus, il n’aime pas parler aux gens de ses aptitudes parce que les gens le traitent comme un ‘singe dansant’ ou pensent qu’il est un menteur. Personnellement, j’aimerais avoir hérité de sa capacité à entendre un mot une fois et à m’en souvenir pour toujours. Cependant, le fait que je n’ai pas hérité cette capacité me rend fier de ce que j’ai appris grâce à un travail acharné et de nombreuses erreurs.