In Thomas King’s novel Green Grass Running Water allusions to historic events and figures, pop culture, and different forms of literature are used to expand the reader’s possibilities for deeper understanding. The novel is still enjoyable if it is not read with the intention of catching all the allusions and puns that King includes however it is a rewarding experience to read a novel that challenges the reader to think more deeply and critically about the written words.

For this assignment I have chosen to analyze the interaction between Latisha and the Canadian tourists in the Dead Dog Café. Although their exchange is brief, lasting only from pages 156 to 169, King has left many hidden Easter eggs for the reader to find, making the chapter a very interesting one.

As Jane Flick notes in her reference guide, all of the tourists who we are introduced to by name are incarnations of past Canadian writers who all have some ties to Indian themes. Flick also notes that all of these figures are known for having exploited “Indianness” for the purposes of their work (154). The writers who we meet in the Dead Dog Cafe are Polly (Pauline) Johnson, Sue (Susanna) Moodie, Archibald Belaney, and John Richardson.

King first introduces the readers to these characters as they exit their tour bus and walk all together into the restaurant. While it appears that the tourists are in good spirits, Latisha and her restaurant staff seem to not enjoy the tourists as much, as can be gained from the chef Billy’s comment – “not Canadian, I hope” (155).

I interpreted the fact that the tourists are all wearing name tags, and are traveling together as possibly being a group on a writers retreat or a research trip for their work. The purpose of their trip is never made explicitly clear, although Sue states that they are “on an adventure,” and Archie’s comment that they are “roughing it” can be read as a direct reference to the title of Susanna Moodie’s famous book Roughing it in the Bush. However it is Archie who says to Latisha “what we really want to see are the Indians” (158).

I think this is King’s way of critiquing the works of the historical figures these characters represent, as all of them are known for exploiting native culture to benefit their writing. Thus we can assume that the research conducted by these past writers for their works, is not far off from the bright and cheery tourists at the Dead Dog Café who make it clear they are looking for an “authentic” Indian experience.

Research on any of the writers who the tourists allude to shows that their works rely on stereotypical Indian themes like the “Indian Maiden”, and the “Noble Savage”. Their works show a clear example of characterizing Indians to suit white audiences.

Archibald Belaney was known for the fraudulent Native identity he chose for himself “Grey Owl” to support his work as a conservationist writer, although he was British and had no Native background. King’s version of Archie is critiqued for this when Polly points out that Archie is from England “but he’s been here for so long he thinks he’s Canadian too” (158).

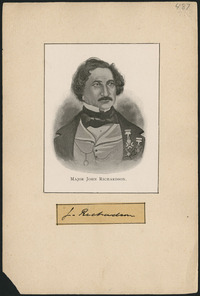

John Richardson was an author known for drawing on the themes of the noble savage, particularly in his 1832 novel Wacousta in which an Englishman transforms himself into a “savage” named Wacousta.

Susanna Moodie’s famous book Roughing it in the Bush, although seeming like a romantic piece meant to inspire sentiments of Canadian nationalism, is actually riddled with racist undertones for relying on the portrayal of Indians as “noble savages”.

Pauline Johnson, who was a Canadian poet of Mohawk and British heritage was known for exploiting her Native heritage to boost her popularity as a poet. This is referenced in King’s chapter when Sue mentions to Latisha that “Polly here is part Indian” (158). Johnson experienced a very privileged upbringing that was more informed by her British heritage, yet she is most known for reading her poetry in traditional buckskin dresses with feathers in her hair, and signing her poems with the name Tekahionwake to emphasize her Native Heritage.

Although Johnson’s Native heritage can be contested, because of the way her poems catered to a white audience, she was also known for writing critically about stereotypes and the challenging circumstances Native people faced in her 1893 short story A Red Girl’s Reasoning. When Polly says to Latisha “its alright, dear, not many people do” (158) when Latisha admits to never having heard of her book, is a reference to the fact that Pauline Johnson’s short stories and books never achieved as much popularity as her poetry.

Further, I think the $20 tip that Polly leaves under the copy of her book The Shagganappi (a book of short stories by Johnson, published after her death in 1913) shows that Polly has a certain level respect for Latisha that is greater than her companions. While the rest leave without supporting the restaurant and don’t purchase any menus (probably due to a perceived lack of authenticity) Polly leaves a more generous tip.

Reading about the works of these writers who the characters in King’s novel represent, I think it is ironic that all of them have claimed either directly or indirectly in their work to be enthusiasts of Native culture, yet as we see with Latisha and her restaurant staff’s reaction to the tourists, they are often quite ignorant. I think this exchange in King’s novel, however brief, is very powerful. By presenting these figures as naive tourists, he is decolonizing a Canadian literary canon that has been built on false and stereotypical representation of Native culture.

Works Cited

Flick, Jane “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass Running Water“. Toronto, Harper Collins, 1994. Web. July 31 2016.

Grey Owl. n.d. Archives of Ontario. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Photograph. Web. July 31 2016.

“Indian Maiden”. TV Tropes. n.p . n.d. Web. July 31 2016.

Johnson, Pauline. “A Red Girl’s Reasoning”. The Mocassin Maker, 1893. Canadian Poetry Press. Web. July 31 2016.

King, Thomas. Green Grass Running Water. Toronto, Harper Collins, 1993. Print.

Macbride, Craig. “CanLit Canon Review #1 : Susanna Moodie’s Roughing it in the Bush”. The Toronto Review of Books. December 7 2011. Web. July 31 2016.

Lock, W. Fredrick. Major John Robinson. 1902. Print. Library and Archives Canada. Web. July 31 2016.

“Noble Savage”. TV Tropes. n.p . n.d. Web. July 31 2016.

“Pauline Johnson”. The Canadian Encyclopedia. n.p. n.d. Web. July 31 2016.

Pauline E. Johnson. McMaster University Library and Archives. Photograph. Web. July 31 2016.

Onyanga-Omara, Jane. “Grey Owl: Canada’s Great Conservationist and Imposter”. BBC News. September 19 2013. Web. July 31 2016.

Susanna Moodie. 1860. National Archives of Canada. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Photograph. Web. July 31 2016.