Prompt: For this week our task was to take the story about how evil comes into the world, written by Leslie Silko and retold by King in his book “The Truth About Stories” and to make the story our own.

Ben Okri- “We live by stories, we also live in them. We are living the stories planted in us early or along the way, we are also living the stories we planted-knowingly or unknowingly- in ourselves (…) If we change the stories we live by, quiet possibly we change our lives.” (King 153)

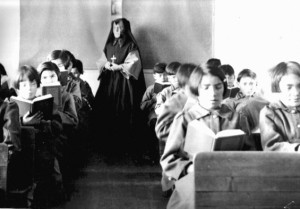

My version: Once upon a time, a little boy went to his first day of school. He arrived in the brightly colored kindergarten classroom, holding his mom’s milky-white hand. He excitedly glanced around the room and realized that the other children were staring at him with questioning looks. He thought maybe it was because he was so tall for his age. After calendar time, recess rolled around. With his Minecraft lunchbox in his hand, he ventured out into the sun. Usually he would want to go play basketball, but eager to make new friends he spotted a group of kids sitting in a circle on the field near the blacktop. Their eyes sparkled with laughter, as they joked around. He walked up, anticipation filling him with every step. His voice faltered as he asked what they were doing. In unison they whispered, “truth or dare” scared that a teacher might hear. Asking if he could join, they agreed, and he sat down in the huddle of small children.

From a boy eating an ant to a girl revealing her crush, there was constant entertainment and glee. Finally, it was his turn to go. His voice faltered as he picked truth. All eyes were on him as he awaited the question. The ant eating boy was given the task at hand and thought it over for a second, whispering to his friends for confirmation. He hesitated and finally asked, “why are you different than your mom? Are you adopted?” The question crashed against him like a glass breaking. He clamped his hand against his ears and shouted, “It doesn’t sound so good, take the story back, take the story back”.

With tears in his eyes, he ran towards the bathroom trying to escape his past, present, and future, somehow hoping to seek shelter in isolation against the story. He walked into the cold bleak bathroom, facing the stained mirror. He wiped away his tears too afraid to look at himself for what he really was. Eventually curiosity took over, and he was forced to look up. Chocolate brown skin filled his view, and he felt denial slowly chipping away. For confirmation he tapped on the mirror to check that the image was authentic, not just a picture in a frame. He gazed for a second, and with new found clarity, he knew a new chapter had been turned. For once a story is told, it cannot be called back. Once told, it is loose in the world. He started to walk back to his classroom finding comfort in his own skin.

Commentary: I work in a middle school and my story is based on stories that I have heard about students experiences with adoption. They reminded me that not all stories are evil or harmful, rather they guarantee that one is living a authentic life as stories hint at human imperfections. I told the story to both of my sisters, as one works in an elementary school and the other attends a middle school. I found that I adapted the story to make it more relevant by using familiar settings and popular fads.

The common thread of denial plays a part in the stories we tell ourselves. My story touches on personal denial, but I find it interesting to look at how groups of people can participate in perpetuating a specific story. The documentary film “Little White Lie” depicts filmmaker Lacey Schwartz who grew up in a white Jewish family in New York, but had darker skin than her parents and siblings. Her family said that she inherited her dark skin from her Sicilian grandfather. The secret was described as a “600 pound gorilla in the room” and at age 18 her mom told her that she was a result of an affair with an African American man. The film illustrates that stories can create a duality of identity in what we tell ourselves and how others see us. The danger of course, is that it can affect the past, present, and future. Luckily, Lacey embraced her identity. However, it begs the question of what role keeping family secrets play in our lives, for the better or the worse?

Works Cited:

Belton, Danielle. “3 Black Adoptees on Racial Identity After Growing Up in White Homes.” The Root . N.p., 27 Jan. 2015. Web. 29 May 2015.

King, Thomas. The Truth About Stories:A Native Narrative. Toronto: House of Anasi, 2003. Print.

Lacey Schwart. Flickr. Web. 29 May 2015. <www.flickr.com>.

Little White Lie Official Trailer. Narr. Lacey Schwartz. Film Fesitvals and Indie Films, 2014. Web. 28 May 2015. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qxHLpgYwcVY>.

Mystical Mirror. 2014. Web. 29 May 2015. <www.pixabay.com>.