Question 3: In order to address this question you will need to refer to Sparke’s article, “A Map that Roared and an Original Atlas: Canada, Cartography, and the Narration of Nation.” Write a blog that explains Sparke’s analysis of what Judge McEachern might have meant by this statement: “We’ll call this the map that roared.”

Before the settlers arrived in Canada, it was assumed that the land was unoccupied, because of the myth that the natives existed in a “state of nature” (Asch 7). Jurisdiction of the land was considered to belong to the settlers. Accordingly, maps were used to legitimize their colonial world through the naming and division of places according to their own beliefs. The maps helped to perpetuate the notion of a “singular national origin” in which Europeans were chapter 1 of the story of Canada (Sparke 468). This version of idealized Canada, was resisted when a cartographic struggle occurred during the Delgamuukw case in May, 1987. The Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan people attempted to gain their national sovereignty by re-mapping themselves into the Canadian story. Their efforts were mocked by Judge McEachern who proclaimed: “we’ll call this the map that roared”. It suggests something that seems threatening, but in reality is very ineffectual.

Sparkes analysis of McEachern’s statement illustrates the irony of the situation. The judge was given something that he should have been able to understand, but instead it unconsciously betrayed his illiteracy. The map resisted against colonial cartography through its “roaring refusal of the orientation systems, the trap lines, the property lines, the electricity lines, the pipelines, the logging roads, (…) and all other accouterments of Canadian colonialism” (Sparke 468). He could not locate himself within this un-traditional map, and thus refused to understand this performance. His illiteracy can be traced back to the settlers such as Susan Moodies husband who “daily consulted (the map) in reference to the names and situations of localities in the neighborhood” (np). Both men’s inability to comprehend First Nation cartography reinforces Asch’s notion that we are chapter 15 in this story of the land. It points to the idea that the land was already occupied with people who had their own distinct and developed cultures. For instance, Susan Moodie describes how when the Indians saw the map “they rapidly repeated the Indian names for every lake and river on this wonderful piece of paper” (Np). It appears that our stories can never be substituted for theirs, and improvements were made when the Supreme Court of Canada overturned his decision. and ruled that oral history could be used in trials.

The introduction of the map during the trial can be seen as a form of protest that is described by Nancy Peluso as “counter-mapping”. It refers to the appropriation by local groups of mapping ” to counterbalance the previous monopoly of authoritative resources by the state or capital” (385-386). Peluso, describes how Indigenous groups in Indonesia mapped forest resources in order to “control representations of themselves and their claims to resources” (387). In all cases of counter-mapping, the main goal is to destabilize dominant representations.

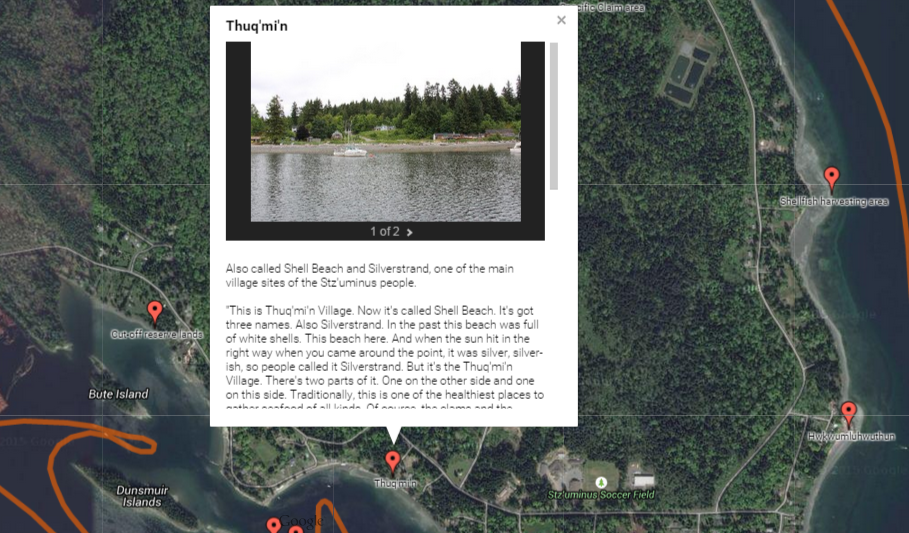

Closer to home, we have started to see counter-mapping take place in the digital world to aid local communities. In Ladysmith, British Columbia, there have been efforts to map Indigenous ancestral lands on google earth. For example, the Stz’uminus Storied Places Project plots names and places of importance in the Hul’q’umi’num’ language. The project aims to aid in the preservation of names and stories and to assert territorial claims to help solve an unresolved land claim. The involvement of individuals such as Stz’uminus First Nation elder Ray Harris ensures that the choices made regarding the maps, is under their control rather than the provinces. Importantly, the accessible nature of these maps through cellphones and computers ensures that the youth will be able to both learn their history and aid in the preservation of their culture.

Works Cited:

Asch, Michael. “Canadian Sovereignty and Universal History.” Storied Communities: Narratives of Contact and Arrival in Constituting Politcal Community. Ed. Rebecca Johnson, and Jeremy Webber Hester Lessard. Vancouver: U of British Columbia P, 2011. 29 – 39. Print.

Hunter, Justine. “Oral history goes digital as Google helps map ancestral lands.” The Globe and Mail. N.p., 11 July 2014. Web. 20 June 2015. <http://www.theglobeandmail.com>.

Moodie, Susanna. Roughing it in the Bush.. Project Gutenburg, 18 January 2004. Web. 18 June 2015.

Peluso, Nancy. “Whose Woods are These? Counter-Mapping Forest Territories in Kalimantan, Indonesia.” Antipode 27.4 (1995): 383-406. Web. 19 June 2015. <https://gisci.files.wordpress.com/2009/02/peluso_whose_woods.pdf>.

Sparke, Mathew. “A Map that Roared and an Original Atlas: Canada, Cartography, and the Narration of Nation.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 88.3 (1998): 463- 495. Web. 18 June 2015.

Hi Sarah,

Great insights and examples! I especially love the term you use to describe Judge McEachern’s response to the “map that roared”: illiteracy. That puts him where people like judges – and colonizers or settlers in general – are rarely put, in the position of not being able to understand. I noticed this dynamic on a shallower level a few days ago, in a movie. The city people trying to find something out in the country asked for directions, and were told to go up the hill, over the bridge, turn at the hill, etc. They asked snobbily if any of these roads had names, and felt very superior. But like Judge McEachern, they were the ones who didn’t know where they were going.

I’m interested to see that quite a lot of people chose to talk about this map question in their post this week. Do you have any thoughts on why it might be a popular choice?

Thanks!

Kaitie

Hi Kaitie,

Thanks for the comment. I think that this question was so popular, because illiteracy still seems to be an ongoing problem in Canada. It does seem to be something that is more prevalent than we think. I liked your example of how the city people didn’t understand the directions, it reminds me of the art project at UBC called “Native Hosts”. There are 12 signs, with backwards letters that say “British Columbia today your host is” and in forward facing letters name one of British Columbia’s Indian bands (such as Lil’wat). Signs like directions are supposed to be readily available to interpret in order to guide someone. These signs attempt to challenge our literacy and authority by making it hard to read. The fact that the Indian band names are forward facing reminds us that the University is located on traditional Coast Salish lands. It is an attempt to challenge perceptions, which evidently could not be done in Judge McEachern’s case.

information on signs: http://www.belkin.ubc.ca/outdoor/

🙂

Hi Sarah! I answered the same question but definitely had different answers. I took the interpretation in a completely different way, mostly my misunderstanding of Judge McEachern’s statement. I thought he was siding with the Indigenous in saying that “the map that roared” meant that it was finally a fight back against gaining their land as rightfully theirs. But your insights made me understand, and really enjoyed, that Judge McEachern’S illiteracy, as what you’ve said, is what is meant by his statement. Which now I could definitely understand better. I really liked how you mapped his position in the case, his lack of understanding the Indigenous history and the settlers thinking it was something they could just take from them. But to challenge your interpretation and to base it off of mine, do you think it’s possible that Judge McEachern could be depicting the map that roared as something positive for the Indigenous fight against the settlers? That it roared because they could finally be heard using their positions in the map?

Also, the oral history getting digitalized in Google Earth is so amazing, I’ve never heard of it! That certainly helps inviting them to our contemporary culture, including them in how we map our homes today.

-Angela Olivares

Hi Angela,

I think that the question for this week that we both answered is so interesting, because there are various ways to interpret it. I don’t think McEachern was siding with them or supporting their map in any way. I think that like many Canadians he was socialized into believing a particular myth (white people came first). To support the map he would have to completely disregard the belief systems that he was brought up with. Furthermore, his response is worded in a mocking way. It is described as “paper tiger” which is something that seems powerful, but is actually ineffectual. It his way to illustrate that their purpose would be impossible to achieve, because it would mean that they would have to contradict the story of how Canada came to be. Which is ingrained in our conceptions of what it means to be Canadian, and in our national image as a peaceful country.

🙂