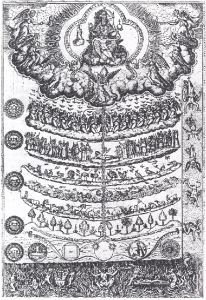

For this weeks blog post regarding “Green Grass Running Water” we were prompted to “discover as many allusions as you can to historical references (people and events), literary references (characters and authors), mythical references (symbols and metaphors)” (Paterson).

The section I was assigned is pages 406-418 in my version of the novel.

Summary: My section primarily focuses on Latisha who explains her past marital problems and resulting single motherhood to empathize with Alberta who is in strong denial of her pregnancy; “there’s no way I can be pregnant” (King 407). Alberta begins to better understand their tense relationship, when George unexpectedly arrives for the Sun Dance and greets Latisha. The section also contains Eli and Harley remarking about the changes that the Sun Dance has undergone over the years, and also the damage that the dam is doing to the river.

Ann Hubert:

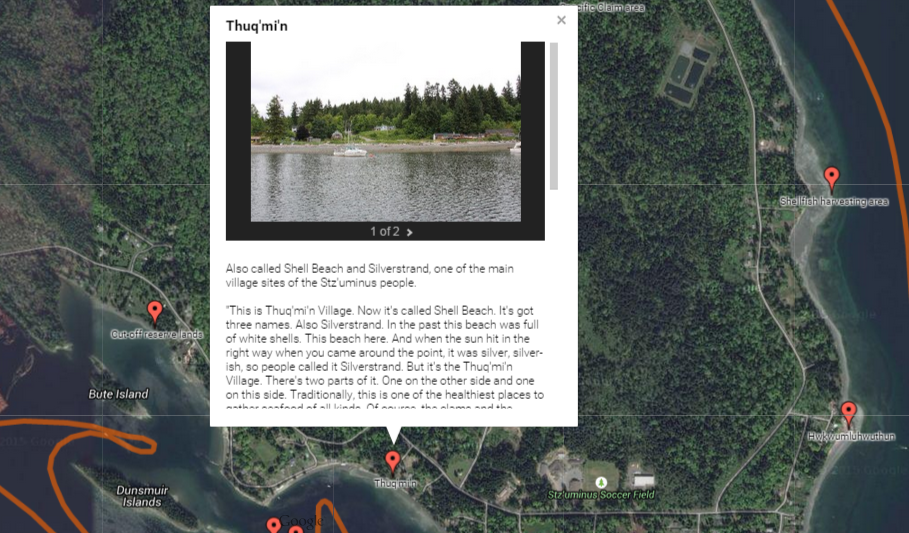

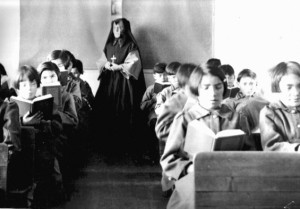

“Ann Hubert, a white girl who wore a new dress to school each week, asked if the Sun Dance was like going to church” (King 409)

Latisha’s arrival for the Sun Dance illustrates how her cultural identity is strongly connected through the generations:”Norma’s lodge was always in the same place (…) And before that Norma’s mother. And before that” (King 409). With seeing the lodge, she is reminded that in the past her cultural identity was challenged by a girl called Ann Hubert. Flick notes that Ann is an allusion to the Canadian novelist, Anne Cameron who also writes as Cam Hubert (161). She famously published “Daughters of Copper Women” in 1961, which retold the oral stories of Nootka women on Vancouver Island. Anne was criticized for her misuse of cultural property that was not hers (Flick 161). Ann Hubert similarly appropriates Latisha’s culture by forcing her own beliefs onto what the Sun Dance is about: “Ann said that it was probably a mystery (…) like God and Jesus and the Holy Ghost” (King 409). Her appropriation is connected to power dynamics and the essentialization of “the other”. Latisha is unable to challenge her, because her voice has been stolen by Ann’s chatter; “in the end she said nothing” (King 410). Jeanette Armstrong, a First Nation author and activist has notably criticized the work of Anne Cameron: “there are a lot of non-Indian people out there speaking on our behalf or pretending to speak on our behalf and I resent that very much; I don’t feel that any non-Indian person could represent our view adequately” (Hoy).

George Morningstar:

“Hello, Country.Even before she turned, Latisha’s arms instinctively came up and she stepped back, setting a distance between herself and the man behind her. “Hello, George,” she said.” (King 412).

George Morningstar (Latisha’s ex-husband) like Ann Hubert presents another example in Latisha’s life where her identity has been appropriated by a white individual. George is an allusion to George Armstrong Custer, a famous United States Army Officer. He was notable for Custer’s last stand, which was a plan to defeat the Lakota. He faced problems when he advanced too quickly which allowed the Lakota, Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors to surround and kill him (“George Armstrong Custer”). Custer’s false expectations of the warriors are reflected in George’s essentialization of Latisha, when he greets her with “hello, country”.Much like Custer he feels a sense of ownership over her, which was evident in how he attempts to claim native identity through his buckskin jacket and exploiting her by remarking how he likes her, because she “is a real Indian” (King 112). Similar to the warriors who defied Custer’s lowly expectations Latisha illustrates resistance by realizing the true nature of George as seen through Alberta’s eyes; “Latisha’s body tensed up, could feel her hands clench” (King 418).

Alberta Now:

“Charlie lay on the bed and thumbed through a copy of Alberta Now” ( 413)

Flick notes that the magazine “Alberta Now” is a play on Ted Byfield’s ultraconservative news magazine “Alberta Report” (151). Byfield’s “Alberta Now” discusses the sentiment of Western discontent and alienation from political affairs.He coined the phrase “the west wants in” which symbolically ties to how Charlie reads about “how old movie Westerns were finding a new life in the home video market” (King 413). This obviously refers to his dad, Portland who starred in Hollywood Westerns. There seems to be the suggestion that Portland is resisting, and fighting back, possibly against societal standards stemming from the stereotypical Indian in the films.

“Maybe we should give the Cree in Quebec a call” (King 416)

Flick notes that this refers to the Cree who managed to delay the Great Whale Project and received millions of dollars after signing the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement in 1975 (102). They also gained control over parts of their land. In this section concerns over the dam are juxtaposed with images of families unpacking “chairs and blankets and dragging them toward the circle” (King 416). It is evident that both Eli and Harley want to achieve the same results as the Cree, because they want the Sun Dance to be “just like the old days” (King 416).

Reflection:

My section follows closely after the incident in Bursum’s store where the Indians in the Western film fight back against their traditional deaths. The same sense of resistance is carried forward with Latisha refusing to let George “colonize” her once again. Similarly,Portland who is Charlie’s father is symbolically reflected in the “Alberta Now” magazine illustrating a resistance against Hollywood tropes. This sections resistance is further solidified with Eli and Harley remarking on how to stop the dam from damaging the river in order to restore the sanctity of the Sun Dance.

Works Cited:

“Alberta Report.” Archives Canada. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 July 2015. <http://www.archivescanada.ca/>.

Cameron, Anne (1938-).” ABC book world. N.p., 2010. Web. 10 July 2015. <http://www.abcbookworld.com/>.

Flick Jane. “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water.” Canadian Literature 161/162 (1999). Web. 4 Apr. 2013.

“George Armstrong Custer .” New Perspectives on the West. PBS, 2001. Web. 11 July 2015.

Hoy, Helen. “How should I read these?.” Insight. N.p., 6 Jan. 2006. Web. 9 July 2015. <http://www.uoguelph.ca/>.

King, Thomas. Green Grass Running Water. Toronto: Harper Perennial, 2007. Print.

Paterson, Erika. “Lesson 3:3.” ENGL 470A Canadian Studies Canadian Literary Genres May 2015. University of British Columbia Department of English, n.d. Web. 10 July 2015.