Question 3: We began this unit by discussing assumptions and differences that we carry into our class. In “First Contact as Spiritual Performance,” Lutz makes an assumption about his readers (Lutz, “First Contact” 32). He asks us to begin with the assumption that comprehending the performances of the Indigenous participants is “one of the most obvious difficulties.” He explains that this is so because “one must of necessity enter a world that is distant in time and alien in culture, attempting to perceive indigenous performance through their eyes as well as those of the Europeans.” Here, Lutz is assuming either that his readers belong to the European tradition, or he is assuming that it is more difficult for a European to understand Indigenous performances – than the other way around. What do you make of this reading? Am I being fair when I point to this assumption? If so, is Lutz being fair when he makes this assumption?

In “First Contact as a Spiritual Performance” Lutz describes how both groups (Native and European) relied on their spirituality to make some sort of sense out each other. His description of their differing belief systems illustrate that his assumptions regarding how the Indigenous have a better understanding of European performance are evidenced in the contact stories.

The natives believed that there was no barrier between the natural and spiritual world. The arrival of the explorers did not destabilize their beliefs, as they symbolized “the ongoing proof of these beliefs” (Lutz, “First Contact” 38). The inclusion is evident in Nuu-chah-nulth stories that recorded that Captain James Cooks vessels were seen to have come from the sky ;“these were the moon men. They wore yellow, had a brass band in their caps, brass buttons” (Lutz, “First Contact” 36). Their broad understanding of the world is evident in various accounts told about the same events by different groups. In all of these accounts Europeans were included whether they were “returned from the land of the dead or peoples from the sky” (Lutz, “First Contact” 38).

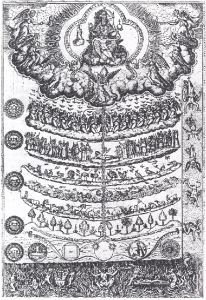

The descriptions of European spirituality differ greatly from those described above. The European belief system contained more rigid categorizations such as the distinction between “sacred and profane” (Lutz, “First Contact” 31). Their individual standing in the world was governed by hierarchies of god, man, animals, plants (Paterson). This is similar to what we know as the “Great Chain of Being”. The presence of the natives symbolized a challenge to their hierarchical beliefs. Initially, they tried to make them recognizable by thinking that the Haidi were “forming themselves in a cross as they approached the ship” (Lutz, “First Contact” 39). However, their total reliance on their belief systems meant that the natives were eventually marked as inferior. Their un-Christianity associated with transformer myths meant that they could not be contained within the same imagined category of “man”. They were unfairly seen as “not fully human” and seemingly took the position at the bottom of the great chain of being (Lutz, “First Contact” 40). The false assumption that natives were irrational dangerously materialized into myths that have been perpetuated today. Furthermore, these assumptions contributed to the idea of Terra nullius (nobodys land) which was the justification for missionaries and the colonization of Canada. The supposed empty land, gave them a clean slate to color their ideas with. This very nation is built on their performances of sanitization.

It is evident based on Lutz’s descriptions of European belief systems, that it would be difficult for those of that tradition to understand Indigenous performances. There is too much reliance on ” non-rational spiritual beliefs” to truly see performances with fresh eyes that wouldn’t be subject to categorization (Lutz, “First Contact” 32). Furthermore, another problem noted by Lutz is that “we are still in that contact zone”. The “contact zone” which contains a struggle to understand another groups culture will always require translation. The problem with translators is that they transform ideas “into something that makes sense to us” (Lutz, “Contact” 11). In Canada, the translation of performances is seen as essential in maintaining the story of the “other”. Paterson succinctly notes, that “we know ourselves through misrepresentations of the other”. News portrayals in Canada of “Indians” illustrate the danger of these translations. For example, the WD4 rule illustrates how Indigenous individuals only make the news if they are a warrior or are drumming, dancing, drunk, or dead.Shaney Komulainen’s iconic picture during the Oka Crisis (see above) illustrates the warrior complex. Protests which usually involve conflict and drama are used by the media to misrepresent the Indigenous as the “uncivilized Indian”. The translation of their performance describes them as a threat to progress in Canada.

Are there any other mistaken representations of Indigenous individuals in the news that are not part of the WD4 rule?

Works Cited:

Great Chain of Being 2 (lighter). 2008. wikimedia . Web. 12 June 2015. <http://commons.wikimedia.org/>.

Komulainen, Shaney. Oka Crisis. 1990. We Move to Canada . Web. 12 June 2015. <http://www.wmtc.ca>.

Lutz, John. “Contact Over and Over Again.” Myth and Memory: Rethinking Stories of Indignenous- European Contact. Ed. Lutz. Vancouver: U of British Columbia P, 2007. 1-15. Print.

Lutz, John. “First Contact as a Spiritual Performance: Aboriginal — Non-Aboriginal Encounters on the North American West Coast.” Myth and Memory: Rethinking Stories of Indigenous-European Contact. Ed. Lutz. Vancouver: U of British Columbia P, 2007. 30-45. Print.

McCue, Duncan. “What it takes for aboriginal people to make the news.” CBC. CBC , 29 Jan. 2014. Web. 12 June 2015. <http://www.cbc.ca/news/aboriginal>.

Paterson, Erika. “First Stories ”. Unit 2 -Lesson 2:2. Vancouver: University of British Columbia. 2015. Instructors Blog.

Snyder, Steve. “The Great Chain of Being.” Grandview University, n.d. Web. 12 June 2015. <http://faculty.grandview.edu>

Hi Sarah,

Great job using Lutz’s take on European and Aboriginal spirituality as the base for your argument – a wise approach. You make a strong point that because Indigenous spirituality had room for previously unknown beings to appear and fit into the belief system, points of first contact were less spiritually disrupting for Indigenous peoples than for Europeans. You compare this flexibility to the rigid beliefs of Europeans, who had more trouble classifying Indigenous people in their hierarchy. Do you think it would be fair to call this narrow-mindedness? And in that case, could we say that settler society’s narrow-mindedness, perhaps stemming from Christian hierarchies as you describe, is at the root of the conflict between Indigenous peoples and settlers in Canada today?

This photo from Oka is one of the most powerful images I know – thanks for including it as a good reminder that we’re talking about now, and not just contact hundreds of years ago.

Thanks,

Kaitie

PS The WD4 rule you refer to is fascinating – I haven’t heard that before, and in trying to think of an answer to your question, examples of Indigenous people in the news who are not warriors, dancing, drumming, drunk, or dead, is showing me how pervasive those tropes are. I’ll keep thinking.

Hi Kaitie,

Thanks for the great comment! I think that narrow-mindedness is definitely a reason why we have conflict in Canada today. I also think that this narrow-mindedness is frequently used as an excuse to prevent other groups from presenting a challenge. When someone says they don’t believe in something, it immediately makes it less legitimate and unrecognizable. It seems to be a technique that keeps the status quo in Canada. By publicly destabilizing other peoples beliefs such as with the WD4 rule they are not allowing any ways to present a challenge. Of course, more recently with First Nation land claims we have thankfully started to see a break in this rigid structure.

Thanks,

Sarah.

🙂

Hi Sarah,

Thanks for your analysis. I agree with Kaitie your use of spirituality as ignition for your argument is very successful. Your piece is well written and clear. I liked your elaboration of ‘performance’ and how you tied this in to a modern day news example. It is poignant that you chose to include the WD4 rule. I hadn’t heard of it either. Performance is such a key part of Gender, Race, and Social Justice Theory. Have you read Judith Butler? Her work on performance and gender has been central to some of my work over the years, and changed my perspective on a static cultural identity. I would agree that spirituality and colonialism are at the heart of the negative stereotypes associated with first nation people.

Thanks for your work and bringing to light this important current issue,

Hannah

Hi Hannah,

Thanks for the comment! Yes, I have heard of Judith Butler as she has been discussed in some of my Sociology classes. Her understanding of gender performance can be applied to First Nations women in Canada. They are subject to social scripts which reinforces the power of the dominant group (white men). They exist in a dominant discourse which describes them as being sexually transgressive, and existing in a zone outside of morality. Thus, they are frequently prone to violence, because it reinforces both their subordination and the white masculinity associated with colonial settlers.

-Sarah

🙂