Question 1:

The distinction between oral and written culture has been described by Foley as the “Great Divide”, symbolizing a competition between the eye and the ear. (MacNeil). It is a mistaken ethnocentric notion that has been dangerously passed down through generations. In MacNeil’s article on “orality” she explores how this binary model is perpetuated by academics such as Walter J. Ong who see that writing is the “key to the evolutionary process,” because it assists in the development of science, history and philosophy. Comparatively, orality is seen as being “imprisoned in the present” and is the mark of a “tribal man” . (MacNeil).

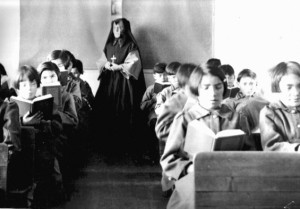

The categorization of people into barbaric and civilized referred to by Chamberlin as “them” and “us” is a social construct that has played a major role in Canada’s colonizing history. Differences in culture were commonly equated with opposition, and the solution that was used was assimilation. Residential schools which Chamberlin describes as a form of “social engineering” removed children from their cultural environment (family) and assimilated them into European culture. They were taught to read/write in English and were prohibited from practicing their language and culture. The loss of orality meant that the children had no agency in the stories of their culture, as MacNeil states that the oral tradition is a useful method “of accessing collective memory”.They instead learnt the stories of the settlers. Thus, as a result, significant cultural loss occurred.

Both MacNeil and Chamberlin (“If this is you land where are you stories?”) agree that such a sharp distinction between oral and written cultures does not exist. Rather, the two traditions interweave and inform each other with a shared common purpose of conveying cultural knowledge through communication. Chamberlin reinforces the similarities by stating that “so called oral culture are rich in forms of writing ( blankets, masks, hats)” and that written cultures have institutions such as schools that have “strictly defined and highly formalized oral traditions” (20). Furthermore, MacNeil explains that with the development of technology the barriers between the two traditions becomes blurred. The fusion of the eye and the ear is apparent in social media apps such as Periscope (twitters live streaming app). This new app challenges Ong’s conceptions of literacy being “durable and permanent” as users can elect to delete their videos and the chat messages immediately after the stream has ended. (MacNeil). Periscope also conveys the centrality of orality in communicating stories. The dialogue between the user and the listener continually shifts and gives the listener a greater power in being able to change the story (Paterson).

Periscope App

Shuswap Elder Mary Thomas has stated that “children are the future”. It certainly appears that way when we look at the role teens and kids play in social media. The power of listeners to change and create stories allows for greater agency in contributing to culture. It appears that Chamberlin’s sentiment about how we need re-imagine “them” and “us” is currently happening online. The awful assimilation that occurred in residential schools due to perceived differences of tradition, is now shifting. The global nature of the web encourages communication through the crossing of cultural boundaries. The mutual sharing of the same platforms (whether it be periscope, twitter, Facebook) allows young people to understand that different cultures view the world in unique ways, which doesn’t make them any less authentic or important. This understanding speaks to how Chamberlin emphasizes the need to cultivate culture as it is what makes us human. He describes that the refusal to do this is like “ a foolish choice between false alternatives. It is a choice between being isolated or being overwhelmed, between being marooned on an island or drowning in the sea” (24) .

Works Cited:

Chamberlin, J. Edward. If this is your land, where are your stories?:Finding Common Ground. Toronto: Vintage Canada, 2003. Print.

Fontaine, Lorena S. “Canadian Residential Schools: The Legacy of Cultural Harm.” Indigenous Law Bulletin 17.4 (2002). Web. 21 May 2015.

MacNeil, Courtney. “Orality.” The Chicago School of Media Theory . U.Chicago, 2007. Web. 20 May 2015.

Paterson, Erika. English 470A: Canadian Studies. University of British Columbia, 2015. Web. 21 May 2015

Periscope, Twitter’s live-streaming app,. Narr. Sam Sheffer. The Verge , 2015. Web. 21 May 2015. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0_0MynsbpOo>.

Periscope. Web. 21 May 2015. <www.softandapps.info>.

Students of Fort Albany Residential School. Wikipedia . Web. 21 May 2015.http://upload.wikimedia/commons/StudentsofFortAlbanyResidentialSchoolinclass.JPG

Hi Sarah,

You discuss how technology has blurred the lines between the oral and written culture but I was wondering about what you thought of Ong’s bold statement that writing is the “key to the evolutionary process”. Or, more specifically, what do you think of Ong’s belief regarding writing elevating consciousness?

After going over the MacNeil reading I thought about how our memories may not be as reliable as we think (http://www.bps.org.uk/news/memory-not-reliable-we-think); and in a predominantly oral culture knowledge is limited to human memory. But maybe this is only so because we’ve been raised in a record-keeping, written, and literate culture and have lost the type of brain power that I would’ve developed had we been raised in a predominantly oral culture.

What do you think?

🙂