If you open up your inbox and see:

Dear Customer,

Due to a recent upgrade, your account must be reactivated […] Click on this link–

–DELETE.

I might not even get to the end of the message before hitting the delete button. It’s the same email patterns screaming red flags for scam: asking to click a link to your bank account or a package waiting for you, or offering an interesting business product or job offer where you need to reply with your personal information. It’s so simple, but such phishing attempts have been around for so long that you guess it has to be working.

Something similar has spread in academic publishing. I receive unsolicited emails from scientific journals with a “call for papers.” Given that it came soon after my first publication, the first time it seemed flattering that they invited me to submit to their journal, but wait… do I believe it when an automated voice says on the phone “Congratulations! You won [insert prize]. Claim your prize by calling us now…”? Nope, I’d stop and hang up.

There are suspicious publishers and academic journals that trick researchers into paying high costs to publish their paper quickly, only later to reveal that the authors had handed off copyrights to their hard research work to a journal or publisher with no credibility. Given the variety of academic journals, it might not be as straight forward as those general scam emails to single out a journal as illegitimate — or a “predatory journal” as we call it — but once you start looking closely, you’ll recognize some recurring warning signs.

Using guidelines to identify predatory journals suggested by Scientific Writing instructor Dr. Nelson-McDermott*, here’s my selection of 5 examples I came across recently where odd – and even entertaining – warning signs made me suspect predatory journals:

#1. Spelling its own name wrong

Spelling mistakes or grammar mistakes in official communications are just some initial signs that you may not want your written work to be published through them…but can it get any better than a careless typo in the title, and in the very first word?

#2. The look-alike

Some predatory journals will call themselves a name incredibly similar to an existing reputable journal. It may only differ from the original by a few words, or it may share an abbreviation like the International Journal of Information Research and Review (IJIRR) and another journal called International Journal of Information Retrieval Research (IJIRR), a subscription journal based in the UK.

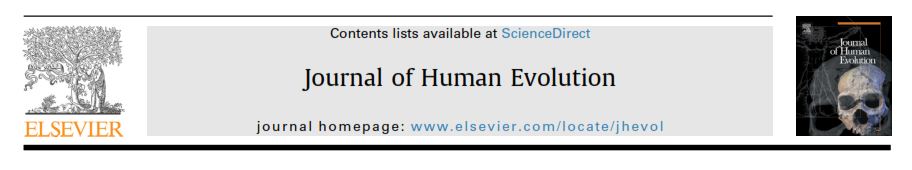

However, the potentially predatory IJIRR goes a step further. I took a look at some of their published articles, and the format of the paper looked very familiar, but slightly “off”. I looked up a paper from a major publisher Elsevier, and it confirmed my suspicions. Here is just the header, and the near-identical tree logo and formatting:

On a quick look, IJIRR may look like it is one of Elsevier’s journals, adding some extra credibility (though being with a credible publisher doesn’t necessarily mean a journal is not predatory).

#3. The jack of all trades (master of none)

Usually, an academic journal has a clearly defined scope that focuses its subject matter. This attracts researchers in that field to contribute articles to help advance the academic discourse within their field. It also reflects the expertise of the editors who would lead a critical peer review of submitted works. However, the extreme opposite case is here – the link speaks for itself:

http://allsubjectjournal.com

When this journal says they will accept papers for 100 subjects and “etc.” (an indefinite number of topics) and have only a handful of editors to cover all those subjects, does the journal get the “best of all,” or just the worst of all, best of none?

#4. Editor-in-Chief profile image is taken from someone else’s

One journal was caught modifying a professors’s profile image to pose as their Editor-in-Chief with a completely different name. This was covered in the Beall’s List: a compilation of potentially predatory journals and publishers, maintained by a dedicated librarian at the University of Colorado Denver, and one of several key references to evaluate possibly predatory journals.

I revisited this questionable journal‘s editorial board page to find that now the profile photo has been replaced to a photo of 4 people together, the Editor-in-Chief unidentified in the photo and lacking an affiliation. When looking at a journal, you want to be able to identify the Editor-in-Chief or other editorial board members to a legitimate affiliation and address.

#5. Journal accepts an absurd article

There was once a crazy news that an article titled “Get me off Your F**king Mailing List” got accepted to a journal. Regardless of the hype and unlikeliness of seeing such an absurd paper in another journal, when the journal publishes questionable papers and claims “fast publication” within a few days to 2 weeks, you really question the quality of peer review and research presented by that journal.

==================

Note about the current situation of open access

*Recently, a course in Scientific Writing challenged me to evaluate the growing trend towards “open-access”, which refers to academic papers that are freely available to the public (instead of subscription-based). When executed well, the shift to open access have their benefits for fast and broadly accessible research. However, unfortunately predatory journals like the ones discussed above have taken advantage of open access online publications and have spread an impression of low quality research and an unethical academic environment. Open access also poses new challenges for financial and behavioral adaptations required by authors (researchers), publishing conglomerates, funding agencies, institutional libraries who pay for subscription, and public readers of research. It is intriguing to follow how open access is developing in different regions, most recently in Canada.