The provincial government says it is ‘improving’ the Agricultural Land Commission.

Modern government speak is interesting. When I want to change the way my course is organized while that course is underway, I don’t describe what I want to do as an improvement. Until I’ve had a chance to hear from everybody in the class, I don’t know if it is an improvement.

I like to believe that our government represents all of us and respects all of us. The very fact that we disagree about who should lead us during an election should, I think, make the winning party humble enough to remember that what they want to do isn’t supported by everyone. I guess the honest statement would be ‘The governing Liberal Party thinks that its changes are improving the Agricultural Land Commission.’

So what are the proposed changes? The government press release can be found here. They are making four main changes to the way the Agricultural Land Commission (ALC) makes it decisions about applications for changing the use of land in the Agricultural Land Reserve (ALR).

- Increase opportunities for farmers to earn a living and continue farming their land,

- Recognize B.C.’s regional differences to better support farming families,

- Improve land use planning coordination with local government,

- Modernize the Commission’s operations.

The press release states that these ‘improvements’ will protect farmland and support farmers. There is nothing in these changes that enhances the protection of farmland. All the changes focus on strengthening regional input into land use decisions and facilitating new activities on agricultural land.

Allowing non-agricultural uses on agricultural land is not a new idea. What can we learn from history? Gravel is a valuable commodity in the rapidly growing parts of the province. In river deltas, such as the Fraser Valley, there are large gravel deposits under farmland. In principle, we could peel back the topsoil, mine the gravel, fill the hole with some other material, and then put the soil back.

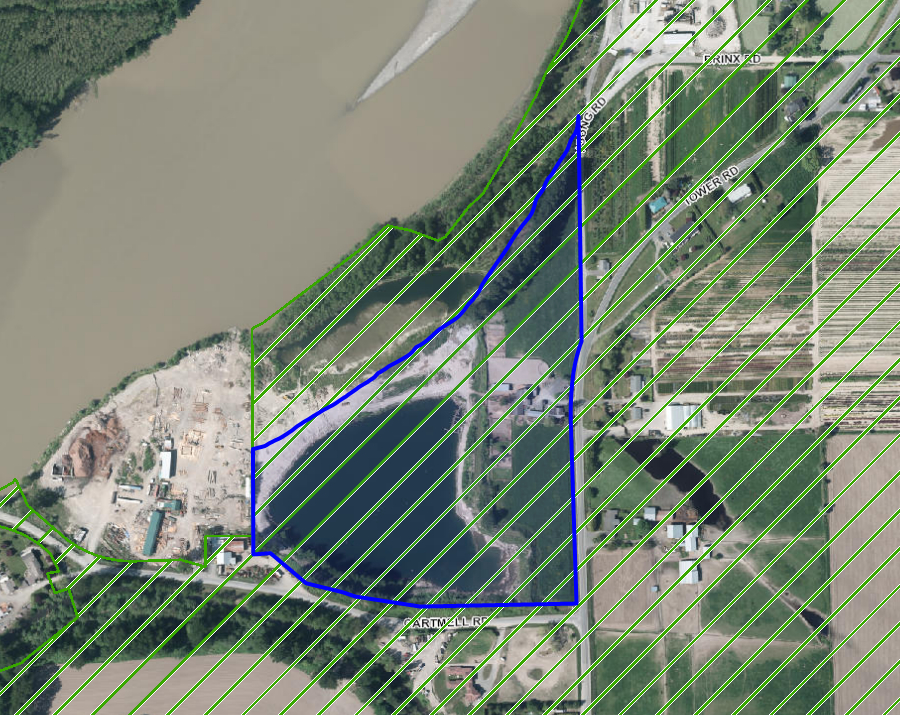

The image above is a screen capture from the maps provided by the City of Chilliwack. The diagonal green lines identify lands that are part of the ALR. The blue line defines one parcel of agricultural land. Half of the parcel is a lake, an abandoned gravel pit.

I grew up on a dairy farm nearby. The plan proposed at the time was that the soil would be moved aside, the gravel removed, the hole filled with sand, and then the soil returned. My late father was convinced that it would never be rehabilitated. Something like twenty years later, there is a dike of stockpiled soil surrounding a pit filled with water. My father was right, and the rehabilitation has not happened.

The promise was made. Why didn’t the reclamation happen? In a 2005 application by the City of Abbotsford to remove lands from the ALR, it estimated reclamation costs at between $20,000 and $50,000 per acre (letter here). This pit covers almost fifteen acres. It would cost at least a quarter million, and perhaps as much as three quarters of a million dollars to rehabilitate this site. Once the gravel has been mined, then there are no further revenues from this site. This creates a pretty strong incentive to avoid paying the rehabilitation costs. Sometimes companies declare bankruptcy. Sometimes they just ignore the rehabilitation until someone tries to enforce the original deal, and then claim they don’t have the money and will go bankrupt if forced to clean up the site. There are plenty of excuses that the mining company can use to avoid the rehabilitation that they have promised to do.

This challenge is not new. Mining operations in the US are required to post a performance bond sufficient to cover the rehabilitation costs of the mine site (Cornell University Law School). They learned through bitter experience that mining companies had this nasty habit of disappearing after they have removed everything of value from the site. The way to deal with this is to require a mining company to post the money up front. That way, no matter what happens to the company, the government has the funds to rehabilitate the site.

Within the details of the changes is entrenching the role of regional boards. These regional boards have a rather checkered history of protecting agricultural land, as documented Ryan Green. Ryan found that when the regional boards were created, exclusion rates increased. Regional boards responded more to the undefined ‘community need’ as justification for exclusions.

We have an agricultural land reserve in this province because we have decided that protecting our ability to grow food here should be protected. Not everyone agrees that we should protect agricultural land this way, and land owners often can’t cash in the same way they could if the ALR didn’t exist. However, the public at large is strongly supportive of the ALR. We need to recognize that if we are not careful in how we implement these changes, it may amount to little more than creating new pathways to get land out of the ALR.

I think we can follow the example of US mining law. Allowing non-agricultural uses of agricultural land – gravel pits, RV parks, etc. – should be accompanied by a performance bond. This bond should be sufficient to pay for the cost of rehabilitating the site to its former agricultural capability or higher.

Will requiring a performance bond make it harder for owners to develop alternate uses? Yes it will. If what they are proposing has a good chance of success, they can certainly find a bank or other partner willing to help finance the bond. If the venture has little chance of success, then requiring a performance bond may make it untenable to being with, which is a good thing. If the venture goes ahead and then fails, the funds are available to clean up the mess. Requiring a performance bond will help filter out those proposals that don’t make financial sense.

One more thing to consider is land with such a performance bond that is subsequently taken out of the ALR. One point of a performance bond is to prevent development on agricultural land which destroys the agricultural value of the land. The aim is to stop these developments being one step towards an exclusion from the ALR. The bond should therefore be forfeit if the land is subsequently excluded. The ALC would use these funds to support rehabilitation elsewhere in the ALR.

Requiring a performance bond and having the owner forfeit the bond if the land is removed from the ALR will help reduce speculation. Land owners who want to get their land out of the ALR need to convince the ALC that, at the least, there will be no net negative impact on agriculture in BC. The first thing owners often try is simply not using the land. After a number of years, the owner will argue that this land has not been farmed for a long time, so taking it out of the ALR won’t have any net impact on agriculture. To accelerate the process, the owner may try to degrade the agricultural value of the land. Then the owner can argue that the land isn’t suitable for agriculture anyhow, and should be taken out of the ALR. A performance bond won’t do anything to stop owners from not using their land or making it available to farmers. However, it can reduce the incentive to degrade the land, if the bond is forfeit should the land actually come out of the ALR. The cost of the owner’s effort to accelerate the exclusion is higher, reducing the likelihood owners will make such choices.

Providing land owners with greater flexibility is generally a good thing. However, we in British Columbia believe that protecting farmland is in the public interest. I hope we can learn from our own past experience and from elsewhere to ensure these changes do in fact protect farmland. I think that a performance bond for uses that degrade agricultural land is one way of doing so.

Follow

Follow