It is kind of difficult to enjoy our beaches right now, on account of the high lake level. The recent flooding has damaged docks and other investments that have been made by waterfront property owners, and many have spent time, effort and money in order to minimize the damage.

The damage to docks in particular has been recognized as an opportunity by some, including our mayor and a few counselors, to look for stronger enforcement of regulations concerning structures on the foreshore. With appropriate permitting, waterfront property owners can install docks. They cannot build other structures on the foreshore. A properly constructed dock will be built to allow passage, either beginning below the high water mark, or incorporating stairs or some other means for the public to pass the dock. Many docks are not built this way. Now that many have to be repaired or rebuilt, it does create an opportunity for inspections to take place and action taken to ensure compliance, so that those who cannot afford to own waterfront property have the opportunity to enjoy the lake that they legally have the right to enjoy.

The damage to docks in particular has been recognized as an opportunity by some, including our mayor and a few counselors, to look for stronger enforcement of regulations concerning structures on the foreshore. With appropriate permitting, waterfront property owners can install docks. They cannot build other structures on the foreshore. A properly constructed dock will be built to allow passage, either beginning below the high water mark, or incorporating stairs or some other means for the public to pass the dock. Many docks are not built this way. Now that many have to be repaired or rebuilt, it does create an opportunity for inspections to take place and action taken to ensure compliance, so that those who cannot afford to own waterfront property have the opportunity to enjoy the lake that they legally have the right to enjoy.

Should we go further? Should we acquire waterfront property to convert it from private residences into beach parks? Is it worth it? What would it cost?

A number of years ago the city produced an excellent document, the Lake Okanagan Shore Zone Plan (City of Kelowna, 1997), that documented many of the issues surrounding our Kelowna lake shore. Among these is the fact that riparian property owners have the right to unimpeded access to the water body on which they border. This means that the province – which owns the foreshore – cannot put up a fence or other barrier as a way to limit trespass from those using the foreshore onto private property. This contrasts with other parks, where the agency in charge often does just this as a means of protecting the rights of adjacent property owners. However, if these land owners are concerned about trespass onto their property, nothing prevents them from putting up such a fence themselves.

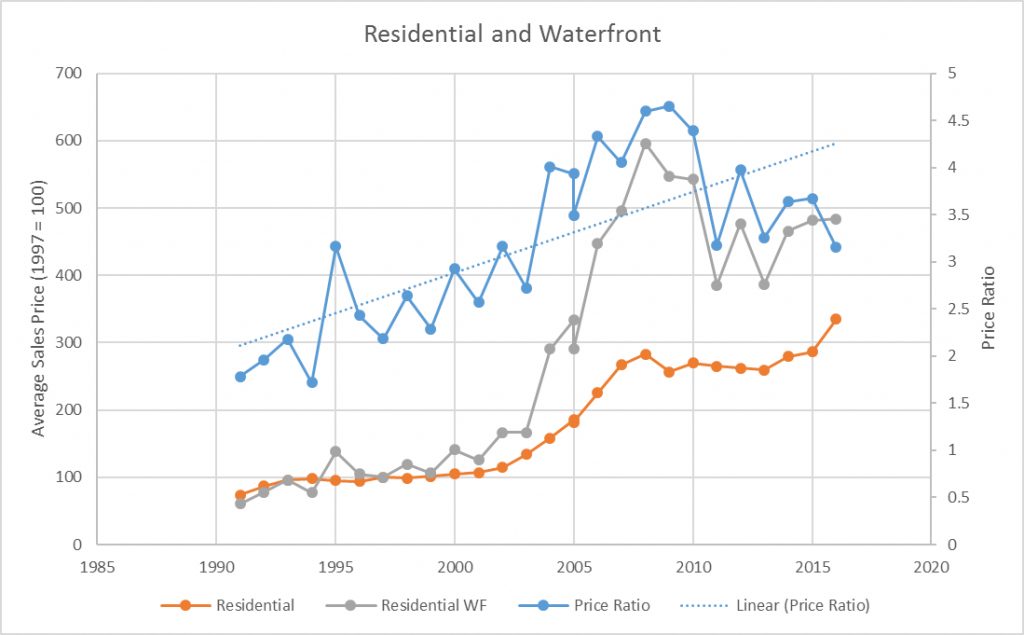

Acquiring lakeshore property to convert it to public parks is expensive. At the time of the study, it was estimated that it would cost between $3,000 and $5,000 per linear foot of waterfront to acquire property for public parks (p35, City of Kelowna, 1997). That is twenty years ago, meaning the cost will be higher today. The graph below shows the changes in the average price of residential properties sold in the Central Okanagan, with and without waterfront (data from the Okanagan Mainline Real Estate Board). I don’t have data specific to Kelowna, so am going to assume that trends for the Central Okanagan are similar to that for Kelowna. From 1997 to the present, residential property prices have more than tripled, while residential waterfront properties have increased in price by almost five times. This suggests that the cost of acquiring lakeshore property could be as high as $25,000 per linear foot.

Herein lies the dilemma. Acquiring lakeshore is expensive, which suggests that taxes will have to be increased to pay for it. The public appetite for tax increases is generally not that large, making it attractive to put off purchasing lakeshore to the future. However, the cost of lakeshore is increasing fast, meaning that the total bill for acquiring lakeshore will be larger in the future.

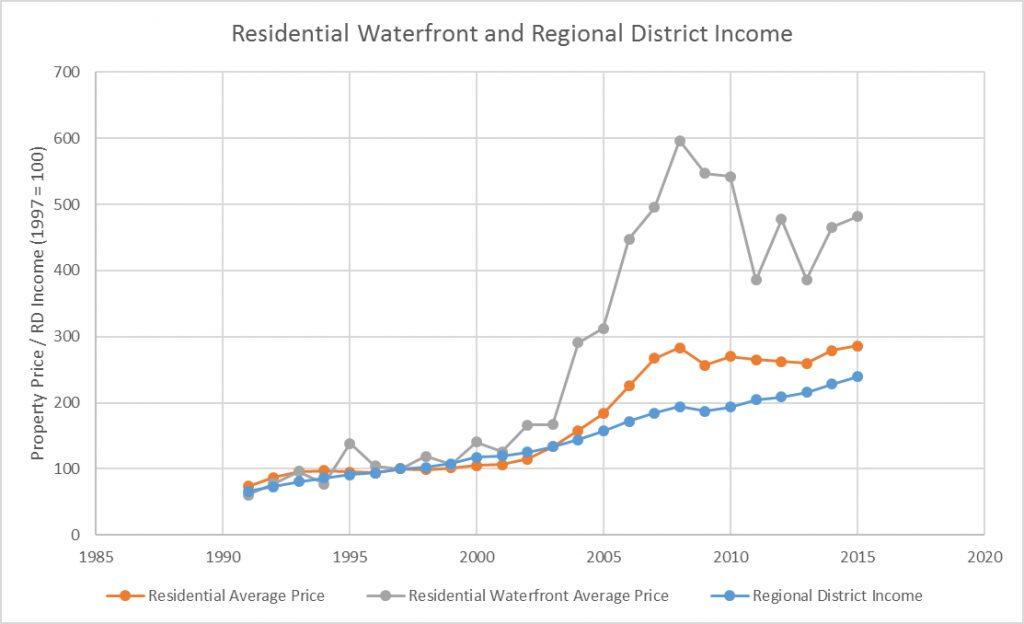

The total bill for acquiring lakeshore seems to be increasing. Is the capacity of the city to pay for acquiring lakeshore also increasing? Our city has grown, incomes have grown, so maybe we are in a better position now to pay to acquire lakeshore. The figure below plots the same property value numbers as above, and adds the total income earned by all the residents of the central Okanagan. This is calculated by multiplying British Columbia’s per capita GDP by the population of the central Okanagan. This is the bottom line on the graph. The population of the Central Okanagan earns a total income that is almost two and a half times what it earned in 1997. However, since waterfront property is almost five times as expensive as it was in 1997, each person in Kelowna would likely have to pay twice as much today to acquire extra lakeshore for the public as they would have had to pay 20 years ago.

To an economist, it is nice to see that markets work. That waterfront prices are increasing relative to properties not on the waterfront is exactly what we would expect from a market. Prices should go up when scarcity increases. Since there is only a fixed amount of waterfront, it becomes relatively more scarce as Kelowna grows, and therefore normal competition bids up the price. While this is true for all properties, the effect is larger for those properties that have something unique, such as being on the lake. There are two effects of this. First, people who own waterfront property gain more from the growth of the city than those who own ‘average’ property. Second, as the value increases, only the more affluent can afford to purchase waterfront residential property, sorting the population into the wealthy who live along the lake, and the rest who cannot.

Is having so much of the lakeshore in private hands truly in the public interest, or is acquiring lakeshore for the public something worth investing in? The data suggests that the longer we wait, the more expensive it is going to get.

A few researchers have come up with estimates of the value of a visit to the beach. Chen (2013) used the travel behavior of Michigan residents to estimate the value of the beaches on Lake Michigan. Since people won’t make the trip unless the value they gain from visiting the beach exceeds the cost, the cost of the trip gives a minimum value for the experience. Chen found that the value was between $32 and $39 per person in 2011 dollars. For the Italian resort town of Lido di Dante, Brandolini estimates a value of 26 to 27 Euro per day visit. Lew and Larson (2008) use the value of people’s time to estimate what a beach visit is worth for San Diego county, finding values in the range of $21 to $23 per day. Penn et al (2016) use a survey approach, where people are asked to choose between different beach configurations. Locals put a greater value on beaches that were less crowded, while tourists would pay more to ensure high water quality. Or, for Kelowna, in the middle of the summer when the beaches are crowded, many locals may just stay home.

A few researchers have come up with estimates of the value of a visit to the beach. Chen (2013) used the travel behavior of Michigan residents to estimate the value of the beaches on Lake Michigan. Since people won’t make the trip unless the value they gain from visiting the beach exceeds the cost, the cost of the trip gives a minimum value for the experience. Chen found that the value was between $32 and $39 per person in 2011 dollars. For the Italian resort town of Lido di Dante, Brandolini estimates a value of 26 to 27 Euro per day visit. Lew and Larson (2008) use the value of people’s time to estimate what a beach visit is worth for San Diego county, finding values in the range of $21 to $23 per day. Penn et al (2016) use a survey approach, where people are asked to choose between different beach configurations. Locals put a greater value on beaches that were less crowded, while tourists would pay more to ensure high water quality. Or, for Kelowna, in the middle of the summer when the beaches are crowded, many locals may just stay home.

Looking at these results, a beach visit in Kelowna could reasonably be worth between $40 and $50, with the value of a visit for all beach visitors increasing if new beach reduces congestion on existing beaches. New beach may also result in more visits if the congestion and other beach characteristics encourage people who are presently staying home that it is now worth going to Kelowna beaches.

So, if we can get an extra 50 feet of beach for $1,000,000, is it worth spending the money? The city of Kelowna looks for a return on investment of at least 1.5% over inflation (Council Policy Manual), which means somewhere between 3 and 4%, or higher. This means that the extra 50 feet of beach would have to attract between 600 and 1000 people per year to all Kelowna beaches, or if the beach season is three months long, approximately 100 days, then it would have to attract on average 6 to 10 people per day. Seems like a pretty easy hurdle to meet.

Are we willing to pay for this? Are we willing to have the city borrow money to invest in more public beach, as we residents of Kelowna will be paying down that debt through our taxes? Are we willing to allow pockets of high density and/or resort development near the lake if in exchange the waterfront property is purchased for public use? Can we convince Victoria and Ottawa that public waterfront is important cultural infrastructure that they should help pay for? I think these are conversations we need to have. The longer we put it off, the more expensive it is likely to get, and therefore we end up with a city where most of the greatest asset we have – the lake – is walled off behind luxury properties that only the wealthiest among us can afford to live in.

- Chen, M. Valuation of Public Great Lakes Beaches in Michigan. 2013. Thesis (Ph.D.) – Michigan State University.

- Brandolini, S. Recreational Demand Functions for Different Categories of Beach Visitor. Tourism Economics. 15, 2, 339-365, June 2009.

- Lew, DK and Larson, DM. Valuing a Beach Day with a Repeated Nested Logit Model of Participation, Site Choice, and Stochastic Time Value. Marine Resource Economics. 23, 3, 233-252, 2008.

- Penn, J; et al. Values for Recreational Beach Quality in Oahu, Hawaii. Marine Resource Economics. 31, 1, 47-62, 2016.

Follow

Follow